Demoralization as a Form of Teacher Burnout

LAURA SOKAL & LESLEY EBLIE TRUDEL University of Winnipeg

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, educational leaders warned UNESCO that attention to the well-being of teachers would be essential to minimize collateral damage from the worldwide virus (Dorcet et al., 2020). They suggested that neglecting teacher welfare would precipitate “a wave of mental health issues and result in disruptions in learning” (Dorcet et al., 2020, p. 10). As a Canadian educational research team, we quickly began working on a multiple-methods research program that would focus on the phenomenon of teacher burnout, new job demands, as well as personal and employment resources, that could be helpful within these new and untested conditions. Over the course of our work, we refined our understanding of teacher burnout through reviewing the published literature. We came to appreciate how the accepted, current conceptualization of teacher burnout came about — even as we identified questions that remained unanswered.

It was over the course of our investigations of teacher burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic that we were introduced to the concept of teacher “demoralization” (Santoro, 2011, 2018). According to Santoro (2011), demoralization is a separate component of teacher attrition distinct from teacher burnout: the distinction rests on the fact that while burnt-out teachers withdraw from their work and students — this as a coping mechanism to address the lack of adequate resources to meet job demands — demoralized teachers anguish over their decision to leave the profession but choose not to remain due to “moral dimensions” (Santoro, 2011, p. 2). That is, demoralized teachers perceive that their current teaching conditions do not allow them to do “good work” and feel that they are therefore denied the moral rewards of teaching (Santoro, 2011). Meeting Torraco’s (2005) call for integrated literature reviews with real-life relevance that can be applied across contexts, we present in this article the most commonly accepted three-component definition of burnout, this as it relates to teachers; it is followed by a detailed conceptualization of demoralization as presented by Santoro. Next, we provide an overview that tracks the evolution of the current understanding of burnout, exploring its expansions and variations across teaching contexts. We consider the possibility that demoralization is a component that is already captured within current conceptualizations of teacher burnout rather than being a distinct construct as proposed by Santoro (2011, 2018, 2020). Finally, we discuss policy and practical implications of including teacher demoralization within the three-dimensional model of teacher burnout.

Background: The Research Informing Our Inquiry into Teacher Burnout

For reader context, our research program began with three quantitative national surveys of a total of 2200 Canadian teachers in April, June, and September 2020 (Babb et al., 2022; Davies & Sokal, 2021; Sokal et al., 2020a, 2020e, 2020f), followed by qualitative analysis of interviews conducted with a sample of these teachers selected to proportionally represent provincial distribution, level of teaching, teacher gender, and subjects taught within the larger national sample (Eblie Trudel et al., 2021; Sokal et al, 2020b). The next phase included teacher surveys using some of the same measures as the national study, as well as semi-monthly telephone interviews of 21 teachers, combined with four focus groups of 20 other teachers conducted at two different time points, as well as surveys and interviews with 16 principals and two divisional leaders (Sokal et al., 2020c, 2020d). Through these studies, we came to appreciate the dynamic nature of burnout as described by our participants. We returned to the research literature to resolve conceptual and theoretical questions related to burnout and demoralization. This return gave rise to the present article.

Following the advice of Snyder (2019) and Torraco (2005), we elected to conduct an integrative review process. An integrative review process selectively pursues research related to theoretical models with the goal of reconceptualization (Snyder, 2019; Torraco, 2005). This process is the preferred review methodology when the research goals are synthesis and critique respecting a narrow research question (Snyder, 2019). In our case, we wanted to know whether demoralization was captured within the current model of teacher burnout. Furthermore, “the purpose of using an integrative review method is to overview the knowledge base, to critically review and potentially reconceptualize, and to expand on the theoretical foundation of the specific topic as it develops” (Snyder, 2019, p. 357). This approach is recommended by Snyder (2019) when the existing research is disparate, as is the case with the conceptualizations of burnout and demoralization, which address two different sets of literature. Integrative review methodology promised to yield an overview of the knowledge base, which would allow us to consider its alignment with Santoro’s claims (2011, 2018).

Our process involved conducting separate literature reviews for each of our published studies and incorporating a snowballing technique, following the publications cited in each article to gather a more in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of burnout. When confronted by research about depersonalization, we isolated and investigated its key claims, analyzing additional work by Santoro. We then tracked the development of burnout research to gain an understanding of how the work of Santoro was supported or refuted, beginning with the nascent 1970’s thinking of Maslach and Pines and following the research trail related to burnout up until its present-day understandings. According to Torraco (2005), “An integrative literature review of a mature topic addresses the need for a review, critique, and the potential reconceptualization of the expanded and more diversified knowledge base of the topic it continues to develop” (p. 357). Given that more than 50 years of research have contributed to a continually refined conceptualization of burnout, this approach proved a good fit for our purpose. Throughout the review process, and up until we experienced saturation in terms of repeated themes and developments without new incoming knowledge, we discussed our ideas and questions as a group, using a critical lens to synthesize the research literature.

Literature Review

What is burnout?

In differentiating between actual burnout and sustained periods of high stress commonly experienced by teachers, one teacher at a workshop on burnout said:

We shouldn’t throw the word ‘burnout’ around. It’s like having a diagnosis of some sort. That’s how we should treat it. We should respect the word a little more and understand that when a teacher gets to the point of being burned out, there could have been so many steps we could have taken to support them. (Walden University, n.d., para 13)

In over 50 years of research, more than 50 different definitions of burnout have been offered, but the most accepted definition has come from Maslach and Jackson (1981), according to Manzano-Garcia and Ayala-Convo (2013). When Maslach and her colleagues first coined the term burnout, it was to describe a distinct, three-component, work-related, psychological syndrome. Dimensions of burnout included “emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment” (Maslach & Jackson, 1984, p. 134) resulting from the stress of interactions between a worker and the recipient of the work (Maslach, 2003); for teachers, the recipient is typically the student. Subsequent researchers such as Feldt et al. (2014) have contributed to the development of the burnout model, upholding its three dimensions. The first component, emotional exhaustion, resulting from the mismatch between job demands and resources, is characterized by a depletion of emotional energy (Larsen et al., 2017); it is an individual state (Schaufeli & Taris, 2005). Although exhaustion is the most easily identified dimension of burnout, on its own it is insufficient to capture the construct (Maslach et al., 2001). The second dimension, depersonalization, refers to an employee’s emotional detachment and distancing from the recipient of the emotional work — in the case of teaching, a distancing of teachers from their students — and functions as a strategy for coping (Larsen et al., 2017; Schaufeli & Taris, 2005). Finally, the consequence of both exhaustion and depersonalization is loss of personal accomplishment, manifested in self-evaluation of inefficacy, lack of achievement, and reduced productivity at work (Maslach et al., 2001); this component is an effect of burnout (Schaufeli & Taris, 2005).

Maslach (2003) has emphasized that teacher stress and teacher dissatisfaction are distinct from burnout as described within the three-dimension model — an important delineation, as not all people respond to stress in the same ways, and people can be dissatisfied with specific job characteristics without burning out (Farber, 2000). While stress and dissatisfaction may lead to the three dimensions of burnout — exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of accomplishment — stress and dissatisfaction alone do not meet the three-dimensional definition of burnout as described by Maslach. Moreover, burnout is not the same as attrition. Although burnout can lead to absences (Schaufeli et al., 2009) and teacher attrition (Brunsting et al., 2014; Shen et al., 2015), it can also manifest in ‘presenteeism’, where burnt-out teachers stay in their roles but erode school morale, diminishing the resilience of their colleagues, and contributing to poor academic and social outcomes in their students (Ford et al., 2019; Maslach et al., 2001)

What is demoralization?

In her research based on 23 teachers’ experiences in the American school system, Santoro (2011, 2018) premised her argument on the claim that “for many teachers, their work is rather a vocation or calling, replete with notions of moral and ethical commitment to their practice and to the students with whom they work” (2011, p. 4). Santoro (2011) described teachers being prevented from accessing the moral rewards of doing “good work” (Gardner et al., 2001, p. 6) when they were required to act in ways they viewed as unethical in their teaching behaviours, a situation she called demoralization. Scott et al. (2001) further showed that teachers understand that “good work” results in making a difference in the lives of their students. According to Santoro (2011), good work is captured in the agency of teachers as professional decision-makers, rather than in the individual teachers themselves. Santoro (2011) demarcated demoralization from burnout, explaining that while burnout focuses on the psychology of the teacher, demoralization addresses the state of the profession; burnout is “when a teacher’s personal resources cannot meet the difficulties presented by work” (p. 3), whereas demoralization is indicated in “situations where the conditions of teaching change so dramatically that they are now inaccessible” and “teachers can no longer do ‘good work’ or teach ‘right’” (Santoro, 2011, p. 3). Porter (2018) has summarized: “Demoralization means you still have resources, but you cannot do the work under the [sic] conditions you find yourself in” (para. 9). Santoro (2018) claimed further that demoralization suggests the problem is a mismatch between the values of the teacher and the policies and practices within schools. In calling for a distinction between attrition as a result of burnout and attrition due to demoralization, Santoro (2011) argued that teacher attrition does not necessarily reflect a lack of hardiness (which can be equated with Maslach’s concept of exhaustion), a lack of commitment (which can be equated with Maslach’s concept of depersonalization), nor a lack of competence (which can be equated with Maslach’s concept of loss of accomplishment). Attrition could be present instead in the form of demoralization when teachers feel as if they are prevented from fulfilling their ethical duties and thus denied the moral rewards of making a difference in students’ lives (Scott et al., 2001), i.e., that come from good work. Attribution of teaching quality, Santoro (2011) has suggested, has focused too much on characteristics of teachers rather than on the conditions that either support or inhibit good work.

Studies of burnout have focused on the “strains and demands of the work of teaching, and the kinds of institutional supports and leadership that can attenuate work pressure” (Santoro, 2011, p. 10). However, Santoro (2018) argued, this approach is fundamentally premised on the belief that teachers are charged with the responsibility to conserve their energy through self-care in order to meet their job demands. For Santoro (2011), preventing demoralization rests on “structuring the work to enable practitioners to do good within its domain” (p. 19).

Elaborating the burnout model components

While our interest is specific to teacher burnout, Maslach and her colleagues also developed a subsequent, more general scale called the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) (Maslach & Jackson, 1981), a useful comparative scale for illuminating the nuances of burnout. This scale also utilized a three-dimensional construct, although it used different terms to describe them. Conceptual conflation and confusion have therefore resulted with respect to whether the terms in the Maslach Burnout Inventor-Educators Survey (MBI-ES) and the MBI-GS refer to the same three components within different contexts or to three qualitatively different components. Given our interest in the construct of demoralization of teachers (Santoro, 2018), we will focus on the differences in the Maslach scales that measure the “depersonalization” component of burnout. Recall that this component recognizes a teacher’s distancing from students as a means of coping with an emotional resource deficit and is viewed as a key distinction between burnout and demoralization (Santoro, 2011).

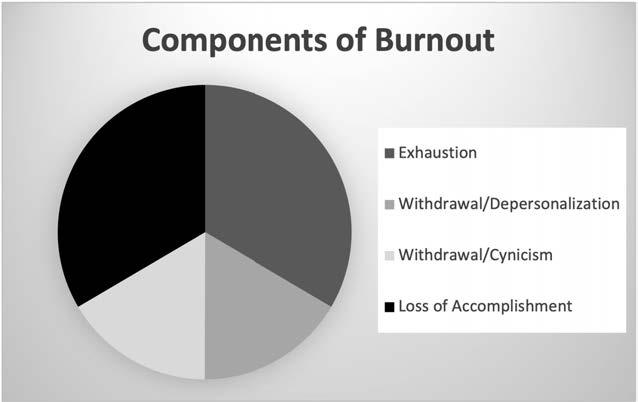

It should be noted that the MBI-ES was a response to evidence of the importance of relationships in teaching and used the term “depersonalization” to describe a distancing from the emotional relationship with students as a means of distancing oneself from the work (Maslach et al., 2001). In the later version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) intended for general use, the term “depersonalization” was changed to “cynicism”, which referred to the attempt to distance oneself from the work itself, rather than from the recipients of the work (the students). Larsen et al. (2017) differentiated depersonalization from cynicism and stated that while depersonalization was defined as “callousness, indifference and objectification of [students]” (p. 162), cynicism meant “lack of work interest and belief in the importance and contribution of one’s work” (Larsen et al., 2017, p. 162). Thus, while both depersonalization and cynicism indicate withdrawal, the object of that withdrawal differs. Figure 1 illustrates the three components of burnout, including both types of withdrawal — from work (cynicism) and from students (depersonalization).

FIGURE 1. Our conceptualization of the components of burnout, 1981 to present (based on literature from 1981to 2021)

Larsen et al. (2017) further investigated the relationship between cynicism and depersonalization to determine whether they were the same construct represented in different job settings or were actually two different constructs. Based on a large study of professionals from eight fields, and where more than 25% were teachers, Larsen et al.’s (2017) confirmatory factor analyses supported their contention that the components of depersonalization and cynicism should be viewed as two separate dimensions of burnout.

Schaufeli and Taris (2005) also defended the need for two different types of instruments to address job demands in the helping professions versus other professions, as the MBI-ES focused on the students while the MBI-GS focused on the teacher’s work itself. They concluded that the three dimensions measured by the educators’ version constituted special cases of the constructs accounted for by the more general version of the MBI.

Schaufeli and Taris (2005) further cautioned that adding more characteristics to the measurement of burnout should be avoided, as it leads to a “laundry-list of dimensions” instead of respecting the “principle of parsimony” (p. 259). However, they also warned against a simplistic view of burnout as encompassing only fatigue. They considered burnout as having at least two dimensions — exhaustion and withdrawal. Specifically, exhaustion is the “inability” to exert more effort whereas depersonalization and cynicism are the “unwillingness” to exert effort as a means of self-protection from depletion (Schaufeli & Taris, 2005, p. 261). They concluded that both the MBI for educators and the more general MBI would be useful in “human service work” — one to measure burnout as a manifestation of work with recipients and one to measure the manifestations of burnout resulting from the work in general. This is an important observation, as it suggests that teachers may withdraw from either their work, their students, OR both — again suggesting that there is a degree of individuality and specificity to processes of burnout in teachers.

The importance of context in burnout

Another important development from Maslach and her colleagues was their consideration of context. Burnout is not solely a psychological construct, something that happens to a teacher alone; rather, it is an interaction between an individual and their job context. Ongoing empirical research has begun to emphasize how burnout can be understood within an industrial-organizational framework as a mismatch (Maslach & Leiter, 1997; Maslach et al., 2001). Maslach and Leiter (1997) have defined mismatch as a situation where a teacher’s psychological contract with their employment situation leaves unresolved issues or where the “working relationship changes to something the worker finds unacceptable” (p. 413) — a context that parallels Santoro’s (2011) description of demoralization as “situations where the conditions of teaching change so dramatically that the moral rewards are now inaccessible” (p. 3). Maslach and Leiter (1997) outlined six domains in which these mismatches can occur: workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values, which we here apply to burnout in teaching. Workload can be understood as the energy necessary to fulfil the work demands (Leiter & Maslach, 2004); for example, planning and implementing effective learning. It can also refer to the emotional workload of teaching students (Bodenheimer & Shuster, 2020) who may be struggling, traumatized, or unmotivated. Workload can be further exacerbated by the energy required to display emotions inconsistent with feelings, this as an expectation of the professional teaching role (Maslach et al., 2001). Control issues arise when a teacher is expected to take responsibility for aspects that exceed their authority, as Maslach et al. (2001) explain: “It is distressing for people to feel responsible for producing results to which they are deeply committed while lacking the capacity to deliver that mandate” (p. 414). Reward involves a mismatch of financial incentives and recognition commensurate with job demands. Community refers to the loss of important relationships in the workplace where employees feel they belong and share common values with peers. Fairness mismatch occurs when an individual perceives a lack of impartiality in their workplace that erodes their self-worth and the sense that they are respected. Lack of fairness results in emotional costs due to distress, but also in cynicism about the workplace. Finally, values mismatch occurs when employees are required to act in ways that they view as immoral or unethical, when personal aspirations conflict with organizational needs, or when mission statements and mandates do not match actual job demands.

Within such a framework, burnout is not conceptualized as the “fault” of the teacher, but rather the result of a mismatch between individual and organizational needs and values. A sustainable, viable teaching position would be a “matched profile [that] would include a sustainable workload, feelings of choice and control, appropriate recognition and reward, a supportive community, fairness and justice, and meaningful valued work” (Maslach et al., 2001, p. 417). However, burnout can occur when even one of these domains is in conflict between the individual and the organization.

If we return to the issue of withdrawal as depersonalization in teachers and cynicism in other professions, we can appreciate how both dimensions of burnout fit easily within the six domains of worklife (Leiter & Maslach, 1999, 2004). For example, within the domain of workload, we can consider the actual time and effort required for teaching tasks, and the emotional work of meeting students’ needs. Whereas withdrawal (or unwillingness) within the context of cynicism might take the form of teachers’ giving minimal planning efforts (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009) and increased absenteeism (Swider & Zimmerman, 2010), withdrawal in the context of depersonalization could look like a suppressing of care or concern for students or failing to present a professional, caring persona especially when feeling angry, upset, tired, or stressed. This is just one example of how both types of withdrawal (depersonalization and cynicism) could affect the mismatch between a teacher and their role context.

Faced with the dynamic nature of burnout across individuals and context, we must conclude that “one size does not fit all” when understanding the personal and organizational resources, demands, and contexts that lead to teacher burnout. How then can we capture these different manifestations of teacher burnout in ways that can usefully guide us in preventing or reversing teacher burnout? If we could develop tools that helped us differentiate between the different manifestations or “profiles” of teacher burnout, perhaps we could tailor interventions to be more responsive to teachers within specific contexts.

Capturing variance in teachers’ burnout experiences

Throughout the evolution of our understanding of burnout, a constant theme has been the tension between capturing individual variations while developing a comprehensive model of burnout (Bianchi et al., 2015). Researchers have cited the need for longitudinal research (Maslach et al., 2001) to determine the antecedents of burnout and the results of attempts to adjust demands and resources on burnout progression (Mäkikangas & Kinnunen, 2016). Research has been hampered by design constraints as well as by limitations in the data analyses used. Statistical approaches that examine differences in teacher burnout based in pre-determined non-latent characteristics such as gender and age do little to capture the dynamic relationship between the individual and their context as it relates to burnout, demoralization, and possibly attrition. Moreover, research has shown that burnout is “contagious” (Herman et al., 2018; Maslach et al., 2001); that a small group of burnt-out teachers can adversely affect the collective morale of faculty and the social and academic outcomes of students (Ford et al., 2019; Maslach et al., 2001). Again, tensions arise between a normalized model or theory and the practical needs generated from individual variation.

Recent developments in statistical practices have offered a new approach to this old, recurring problem in the form of latent profile analysis (LPA) (Mäkikangas & Kinnunen, 2016; Pyhalto et al., 2020). While traditional cluster analysis looks for relationships between variables based on the analyst’s preconceived hypotheses, LPA is a person-centered approach that begins with each participant’s collective latent variables and then evaluates models to find groups of recurring patterns or “profiles.” Through using these procedures, each sample or population generates its own number and types of profiles that capture similarities and differences in subgroups from that specific occupation. LPA is relatively new, but some initial research related to teacher burnout has generated promising findings, specifically in pinpointing job demands and resources that are salient as responses to different groups of teachers (Meyer et al., 2013; Babb et al., 2022).

Moeller et al. (2018) have suggested that this type of modeling would allow us to understand patterns of seemingly discordant combinations of factors within individuals, such as teachers who remain engaged even as they burn out; or teachers who perceive high accomplishment concurrent with exhaustion and depersonalization (Sokal et al., 2020f). While it is to be expected that there would be a group of teachers with high exhaustion, high depersonalization, and high loss of accomplishment as well as a group with low levels in each of these dimensions, LPA allows researchers to uncover the less anticipated groups, such as those with high levels in only one or two dimensions. Several studies have verified not only that various profiles of teacher burnout exist within a given population but also that the number and nature of these groups differ by population, therefore capturing the unique interplay between the individuals and the context in each study. For example, whereas Pyhalto et al. (2020) identified five distinct profiles that differed in both burnout symptoms and proactive strategy use, Salmela-Aro et al. (2019) found only two: Engaged (30%) and Engaged-Burnout (70%). The Engaged group had access to greater job resources and personal resources, whereas the Engaged-Burnout group had greater job demands.

LPA is now being recommended by the some of the authors of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Leiter & Maslach, 2016). When combined with longitudinal study designs, this procedure has the capacity to reveal whether individuals with high scores in only one dimension of burnout are moving toward or away from burnout based on changing conditions related to job resources and demands. Combined with results from their measure of mismatch within the six domains (Leiter & Maslach, 1999, 2004), LPA has the capacity to capture not only the psychological characteristics of teacher burnout and the job resources and demands of a specific context, but also the match or mismatch between them in terms of workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values (Maslach & Leiter, 1997). Like Leiter and Maslach (2016), Herman et al. (2018) have highlighted the practical application of identifying the meaningful and salient features of each profile group and their uniqueness in terms of differentiated responses to mitigate teacher burnout.

Critical Analysis and Findings: Is Demoralization a Profile of Burnout?

Santoro posited that responding to teacher demoralization begins with recognizing that the issue of demoralization should not be categorized as burnout (as cited in Porter, 2018), on the grounds that each condition requires a different response. With an intent to inform interventions that minimize attrition and maximize instructional quality, we return to the question that provoked this exploration of the evolution of our understanding of burnout: Is demoralization an additional component of burnout or a condition separate from burnout?

To answer this question, we need to examine the two main claims regarding distinctions between burnout and demoralization. First, Santoro (2011) claimed that burnout focuses mainly on the psychological processes of the individual at the expense of a systems focus. Second, she claimed that the main distinction between cynicism / depersonalization and demoralization was the emotional withdrawal characteristic of burnout, which is not necessarily the case with demoralization (Santoro, 2011). Let us address each in turn.

First, copious evidence refutes the claim that burnout research and theorizing has focused on psychological processes of teachers at the expense of systemic critical analysis. While it is true that the MBI scales measure psychological processes and are the most commonly used scales in burnout research, they serve only as a beginning for understanding teachers’ burnout within the context of their broader educational setting, pointing to areas where systemic modification could be made. Prior to the 21st century, interventions to prevent or reverse burnout had mainly focused on the individual. Personal characteristics such as younger age, less work experience, low sense of control, and negative attitudes toward change were found to predict higher levels of burnout (Maslach et al., 2001). Therefore, addressing burnout interventions at an individual level appeared pragmatic in two respects: (1) it respected the agency of the individual; (2) it was recognized that it was easier to change individuals than it was to change organizations (Maslach et al., 2001). However, even at that time, both practically and theoretically, researchers including Maslach were overt in stating that:

a focus on the job environment, as well as on the person in it, is essential for interventions to deal with burnout. Neither changing the individual or changing the environment is enough; effective change occurs when both develop in an integrated fashion. (Maslach et al., 2001, p. 419)

Even at its most nascent stages, Pines and Maslach (1978) focused their understanding of burnout on an interaction between the individual and the environment. Indeed, as we have discussed, Maslach and her team developed their theorizing since the late 1990’s to capture this dynamic relationship within the worklife model (via six possible domains of mismatch; Leiter & Maslach, 1999, 2004), supporting in practice their theoretical claims that interactions between individuals and contexts precipitate or inhibit burnout.

Theories and models have not only addressed psychological processes of burnout, but have also addressed moral and existential issues related to teacher burnout and attrition in ways similar to those proposed by Santoro (2011). For example, work by Schaufeli and Enzmann (1998) explored the tensions between teacher expectations and ideals versus demands of the reality of teaching. Maslach and Leiter (1997) likewise acknowledged that “burnout directly affects the values and hopes of people, causing vocational and existential questioning” (p. 415). Pines (1993) developed a model that examined highly motivated teachers who strongly identified as teachers and focused on their increased frustrations when their teaching did not make a meaningful contribution. Based on large cross-cultural samples using both qualitative and quantitative methods, she linked teachers’ inability to garner the existential rewards of teaching with burnout (Pines, 2002). Her main argument was that the most emotionally demanding aspect of a work situation is its lack of existential significance (Pines, 1993). Furthermore, she linked causes of this lack of fulfillment with an interchange between the individual and the context based on a “denial of the significance of one’s efforts” (Pines, 2002, p. 124) and feelings “that they cannot do the work the way it should be done” (Pines, 2002, p. 125). This observation mirrors Santoro’s (2011) conceptualization of “good work”. Gil-Monte et al. (1995) similarly addressed existential meaning in teachers’ work that is challenged by organizational structure and climate. Furthermore, the worklife model of burnout explicitly stated that values are “at the heart of people’s relationships with their work” (Leiter & Maslach, 2004, p. 99) and that a mismatch in the domain of control can result “when workers are unable to shape their work environment to be consistent with their values” (Leiter & Maslach, 2004, p. 96). Thus, neither the claim of a focus solely on psychology at the expense of contextual factors nor lack of attention to existential factors related to burnout are empirically supported in the literature we reviewed.

In terms of Santoro’s (2011) second claim that demoralization is distinct from burnout due to the focus on teacher withdrawal in conceptualizations of burnout, the key issue appears to be the distinction between emotional withdrawal from work (cynicism) and from people (depersonalization) that is essential to burnout but not to demoralization. However, if we consider the cynicism / depersonalization dimension as an unwillingness (as opposed to inability characterized by exhaustion), we can see that cynicism / depersonalization and demoralization are both captured in this dimension. As mentioned previously, cynicism is an unwillingness to exert emotional energy toward the work of teaching; depersonalization is the unwillingness to expend emotional energy toward the recipients of teaching; while demoralization is the unwillingness to exert energy toward the perceived corruption of an unethical system of teaching. Whereas teachers who leave the profession due to high levels of cynicism or depersonalization do so because they are no longer willing to expend resources toward work or students, demoralized teachers leave because they no longer wish to expend energy fighting a system that does not support their ideals of good work. In each case, the individual is making a decision to withdraw their efforts as a way of self-preservation. The key difference between demoralization and burnout characterized by cynicism and depersonalization lies not in the absence of withdrawal, but in the object of that withdrawal, suggesting that — as with the difference between depersonalization in human services setting and cynicism in other settings — the setting and context are key factors in determining the type of withdrawal that occurs.

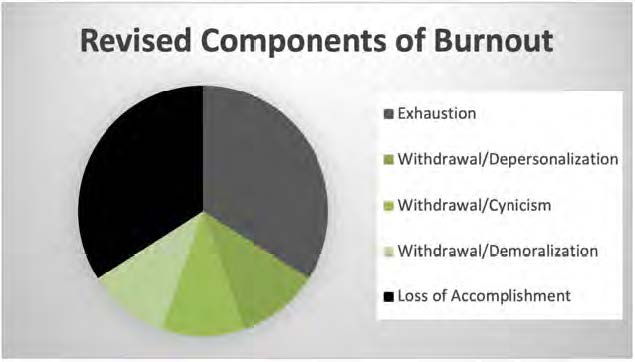

Santoro’s (2011) development of the concept of demoralization seeks to understand burnout as a dynamic relationship between individuals and their responses to their contexts. Just as LPA suggests that teachers within different profile groupings will experience demands and resources (both internal and external) differently, so will teachers experiencing what Santoro (2011) calls demoralization. Building on Maslach’s early recognition (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) of differences between withdrawing energy exerted towards work (cynicism) and withdrawing emotional energy expended towards students (depersonalization), perhaps it is important to examine whether withdrawal of energy exerted toward systems is a third form of withdrawal, which can be captured within theorizing about teacher burnout (see Figure 2). Indeed, Schaufeli and Taris (2005) have suggested that, although the MBI-ES measures depersonalization, and the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) measures cynicism, either or both depersonalization or cynicism could contribute to teacher burnout — depending on the job context, including demands and resources. Likewise, it would be prudent to measure demoralization alongside cynicism and depersonalization as a means of uncovering the mismatch between teachers and contexts to decrease attrition and improve schools. In this way, we can respond to an underlying tension that has followed burnout research for almost 50 years — that of capturing individual variation of experiences of burnout within broader contexts of educational structures.

FIGURE 2. Our reconceptualization of the components of burnout

Policy and Practice Implications of Demoralization as Teacher Burnout

While the discourse on burnout might well be influenced by psychological approaches, the concept of demoralization is clearly socially constructed (Tsang & Liu, 2016). In addition to factors such as individual personality, coping strategies, or mental health, social factors such as occupational context, systemic practices, and organizational hierarchy can ultimately contribute to negative experiences for teachers, as seen through a lens of demoralization. A study by Lau et al. (2008) noted the importance of administrative support for the instructional work of teachers, the influence of school administration on teacher morale, the salience of consultation and open communication during decision-making processes, as well as trust for and consideration of the difficulties encountered in classrooms. By ensuring that these systemic practices were in place, school administrators were able to empower teachers to positively interpret instructional values and make a difference in students’ lives. Administrative support enabled teachers to perceive that their work and their instructional settings matched their goals in teaching. Demoralization was effectively averted, and teacher well-being and instructional quality was enhanced through processes of transformational leadership (Bass, 1990; Dworkin et al., 2003; Leithwood, 2004; Leithwood & Beatty, 2008). Santoro (2018) has noted that teachers could mobilize their power and reengage with the profession if they could locate an authentic professional learning community. Santoro (2018) concluded counterintuitively that while the typical advice to avoid burnout would suggest teachers do less, it was rather about doing more, but under the correct conditions.

Recognition of demoralization as a form of burnout has policy and practice implications. Herman et al. (2018) have highlighted the practical applications of identifying the meaningful and salient features of each profile group by using latent profile analysis, and Bakker and Devries (2021) have recommended a multi-level response to burnout that is supportive to individual, school-based, and systemic causes of burnout. LPA recognizes that different causes and manifestations of burnout require differentiated responses, addressing Santoro’s unfounded concern that burnout mitigation cannot address the conditions that promote demoralization (Porter, 2018). Likewise, the World Health Organization (2018) redefinition of burnout has recognized that mitigating burnout is a joint and mutual responsibility of both individuals and organizations in terms of managing chronic workplace stress. In capturing demoralization as a component of burnout, we recognize that addressing teacher burnout must extend beyond an individual teacher’s self-regulation and beyond simple recalibration of on-site job demands and resources. In addition, recognition of the demoralization of teachers as a form of burnout asks administrators to take steps to ensure a better match between educational policy, system practices, and the moral values of educators. Indeed, in a time of global pedagogical reform prompted by the pandemic, philosophical questions about the desired roles and purposes of education have been highlighted in compelling ways. Reconciliation of the mismatches between government directives, administrative practices, and teachers’ values and morals related to education will be necessary to ensure that a healthy teaching force is maintained and that healthy school environments are supported. If not, it is likely that the pandemic-related warning expressed to UNESCO by Dorcet et al. (2020) will be realized, and education will continue to be disrupted, at great cost to students, teachers, families, and society.

References

Babb, J., Sokal., L., Eblie Trudel, L. (2022). THIS IS US: Latent profile analysis of Canadian teachers’ resilience and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Education, 45(2), 555-585. http://dx.doi.org/10.53967/cje-rce.v45i2.5057

Bakker, A, & Devries, D. (2021). Job-demands resources theory and self-regulation: New explanation and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 34(1), 1-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695

Bass, B. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational Dynamics, 18(3), 19-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(90)90061-S

Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I. S., & Laurent, E. (2015). Is burnout separable from depression in cluster analysis? A longitudinal study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(6), 1005–1011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0996-8

Bodenheimer, G., & Shuster, S. (2020). Emotional labour, teaching and burnout: Investigating complex relationships. Educational Research, 62(1) 63-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2019.1705868

Brunsting, N. C., Sreckovic, M. A., & Lane, K. L. (2014). Special education teacher burnout: A synthesis of research from 1979 to 2013. Education & Treatment of Children, 37(4), 681–712. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/etc.2014.0032

Davies, B., & Sokal. L. (2021). What do a boat and a puzzle have to do with teachers during COVID-19? [podcast]. Research Questions. https://m.soundcloud.com/user-951740369/episode-4-what-do-a-boat-and-a-puzzle-have-to-do-with-teacher-burnout-during-covid-19

Dorcet, A., Netolicky, D., Timmers, K., & Tuscano, F. (2020). Thinking about pedagogy in an unfolding pandemic: An independent report on approaches to distance learning during the COVID19 school closures [An independent report written to inform the work of education international and UNESCO]. https://issuu.com/educationinternational/docs/2020_research_covid-19_eng

Dworkin, A., Saha, L., & Hill, A. (2003). Teacher burnout and perceptions of a democratic school environment. International Education Journal, 4(2), 108-120. https://researchers.anu.edu.au/publications/29993

Eblie Trudel, L., Sokal, L., & Babb, J. (2021). Teachers’ voices: Pandemic lessons for the future of education. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 15(1), 4-19. https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v15i1.6486

Farber, B. A. (2000). Treatment strategies for different types of teacher burnout. Psychotherapy in Practice, 56, 675-689. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200005)56:5%3C675::AID-JCLP8%3E3.0.CO;2-D

Feldt, T., Rantanen, J., Hyvönen, K., Mäkikangas, A., Huhtala, M., Pihlajasaari, P., & Kinnunen, U. (2014). The 9-item Bergen Burnout Inventory: factorial validity across organizations and measurements of longitudinal data. Industrial Health, 52(2),102-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2013-0059.

Ford, T. G., Olsen, J., Khojasteh, J., Ware, J., & Urick, A. (2019). The effects of leader support for teacher psychological needs on teacher burnout, commitment, and intent to leave. Journal of Educational Administration, 57(6), 615-634. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JEA-09-2018-0185

Gardner, H., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Damon, W. (2001). Good work: When excellence and ethics meet. Basic.

Gil-Monte, P. R., Pieró Silla, J. M., & Valcárcel, P. (1995). El síndrome de burnout entre profesionales de enfermería: Una perspectiva desde los modelos cognitivos de estrés laboral. In L. Gonzales Fernandes, A. De la Torre, & J. De Elena (Eds.), Psicología del trabajo y de las organizaciones, gestion de recursos humanos y nuevas tecnologías (pp. 211- 224). Eudema.

Herman, K., Hickmon-Rosa, J., & Reinke, W. (2018). Empirically derived profiles of teacher stress, burnout, self-efficacy, and coping and associated teacher outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavioural Interventions, 20(2), 90-100. http://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717732066

Jennings, P., & Greenberg, M. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491-525. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693

Larsen, A. C., Ulleberg, P., & Rønnestad, M. H. (2017). Depersonalization reconsidered: An empirical analysis of the relation between depersonalization and cynicism in an extended version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Nordic Psychology, 69(3), 160–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2016.1227939

Lau, P., Chan, R., Yuen, M., Myers, J., & Lee, Q. (2008). Wellness of teachers: A neglected issue in teacher development. In J. Lee & L. Shiu (Eds.), Developing teachers and developing schools in changing contexts (pp. 101-116). The Chinese University Press.

Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (1999, spring). Six areas of worklife: A model of the organizational context of burnout. Journal of Health and Human Services Administrators, 472- 489.

Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2004). Areas of worklife: A structured approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. In P. Perrewé & D. C. Ganster, (Eds.), Research in occupational stress and well being: Emotional and physiological processes and positive intervention strategies, (pp.91-134). JAI Press/Elsevier.

Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2016). Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burnout Research, 3(4), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2016.09.001

Leithwood, K. (2004). Educational leadership: A review of the research. Laboratory for Student Success.

Leithwood, K., & Beatty, B. (2008). Leading with teacher emotions in mind. Corwin Press.

Mäkikangas, A., & Kinnunen, U. (2016). The person-oriented approach to burnout: A systematic review. Burnout Research, 3, 11-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2015.12.002

Manzano-Garcia, G., & Ayala-Convo, J. C. (2013). New perspectives: Towards an integrated concept of “burnout’ and its explanatory models. Anales de Psicología, 29, 800-809.

Maslach, C. (2003). Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 189-192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01258

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behaviour, 2, 99-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1984). Burnout in organizational settings. Applied Social Psychology Annual, 5, 133-153.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. (1997). The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. Jossey-Bass.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W., & Leiter, M. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397-422.

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, L. J., & Vandenberg, R. J. (2013). A person-centered approach to the study of commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 23, 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2012.07.007

Moeller, J., Ivcevic, Z., White, A. E., Menges, J. I., and Brackett, M. A. (2018). Highly engaged but burned out: Intra-individual profiles in the US workforce. Career Development International, 23, https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-12-2016-0215

Pines, A. M. (1993). Burnout: An existential perspective. In W. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, & T. Marek (Eds.), Professional burnout: Recent development in theory and research (pp. 19-32). Taylor & Francis.

Pines, A. M. (2002). Teacher burnout: A psychodynamic existential perspective. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8(2), 121–140.

Pines, A. M., & Maslach, C. (1978). Characteristics of staff burnout in mental health settings. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 29(4), 233–7.

Porter, T. (2018). Addressing the demoralization crisis: Why teachers are quitting and how to stop them. Bowdoin College. https://www.bowdoin.edu/news/2018/11/addressing-the-demoralization-crisis-why-teachers-are-quitting-and-how-to-stop-them.html

Pyhalto, K., Pietarinen, J., Haverinen, K., Tikkanen, L., & Soini, T. (2020). Teacher burnout profiles and proactive strategies. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 36, 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00465-6

Salmela-Aro, K., Hietajärvi, L., & Lonka, K. (2019). Work burnout and engagement profiles

among teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(2254). http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02254

Santoro, D. A. (2011). Good teaching in difficult times: Demoralization in the pursuit of good work. American Journal of Education, 118(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1086/662010

Santoro, D. A. (2018). Is it burnout? Or demoralization? Educational Leadership, 75, 10-15.

Santoro, D. A. (2020). The problem with stories about teacher "burnout." Phi Delta Kappan, 101(4), 26–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0031721719892971

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Van Rhenen, W. (2009). How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(7), 893–917. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/job.595

Schaufeli, W., & Enzmann, D. (1998). The burnout companion to study and practice: A critical analysis. Taylor & Francis.

Schaufeli, W., & Taris, T. (2005). The conceptualization and measurement of burnout: Common ground and worlds apart. Work & Stress, 19(3), 256–262.

Scott, C., Stone, B., & Dinham, S. (2001). “I love teaching but…” International patterns of teacher discontent. Educational Policy Analysis Archives, 9(28), 1-18.

Shen, B., McCaughtry, N., Martin, J., Garn, A., Kulik, J., & Fahlman, M. (2015). The relationship between teacher burnout and student motivation. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 519-532. http://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12089

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Sokal, L., Eblie Trudel, L., & Babb, J. (2020a). Canadian teachers’ attitudes toward change and technology, efficacy, and burnout during the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research- Open. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100016

Sokal, L., Eblie Trudel, L., & Babb, J. (2020b). I’ve had it! Factors associated with burnout and low organizational commitment in Canadian teachers during the second wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research- Open. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666374020300236

Sokal, L., Eblie Trudel, L., & Babb, J. (2020c). Opportunity solving: Ordinary people doing extraordinary things, every day. Education Canada. https://www.edcan.ca/articles/opportunity-solving/ This article was invited as a department article, and then elevated to the lead article for a three-volume series on teacher wellness.

Sokal, L., Eblie Trudel, L., & Babb, J. (2020d). It’s okay to be okay too. Why calling out teachers’ “toxic positivity” may backfire. Education Canada, 60(3). https://www.edcan.ca/articles/its-ok-to-be-ok-too/

Sokal, L., Eblie Trudel, L., Babb, J. (2020e). Supporting teachers in times of change: The job demands-resources model and teacher burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Contemporary Education, 3 (2). http://redfame.com/journal/index.php/ijce/issue/view/243

Sokal, L, Eblie Trudel, L., & Babb, J. (2020f) COVID-19’s Second Wave: How are teachers faring with the return to physical schools? https://www.edcan.ca/articles/covid-teacher-survey-2/

Swider, B., & Zimmerman, R. (2010). Born to burnout: A meta-analytic path model of personality, job burnout and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 76(3), 487-506. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.01.003

Torraco, R. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4, 456-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283

Tsang, K., & Liu, D. (2016). Teacher demoralization, disempowerment, and school administration. Qualitative Research in Education, 5(2), 200-225. https://doi.org/10.17583/qre.2016.1883

Walden University. (no date). The resilient educator: Recognizing the signs of teacher burnout. https://www.waldenu.edu/online-masters-programs/ms-in-education/resource/the-resilient-educator-recognizing-the-signs-of-teacher-burnout

World Health Organization. (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th revision). https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases