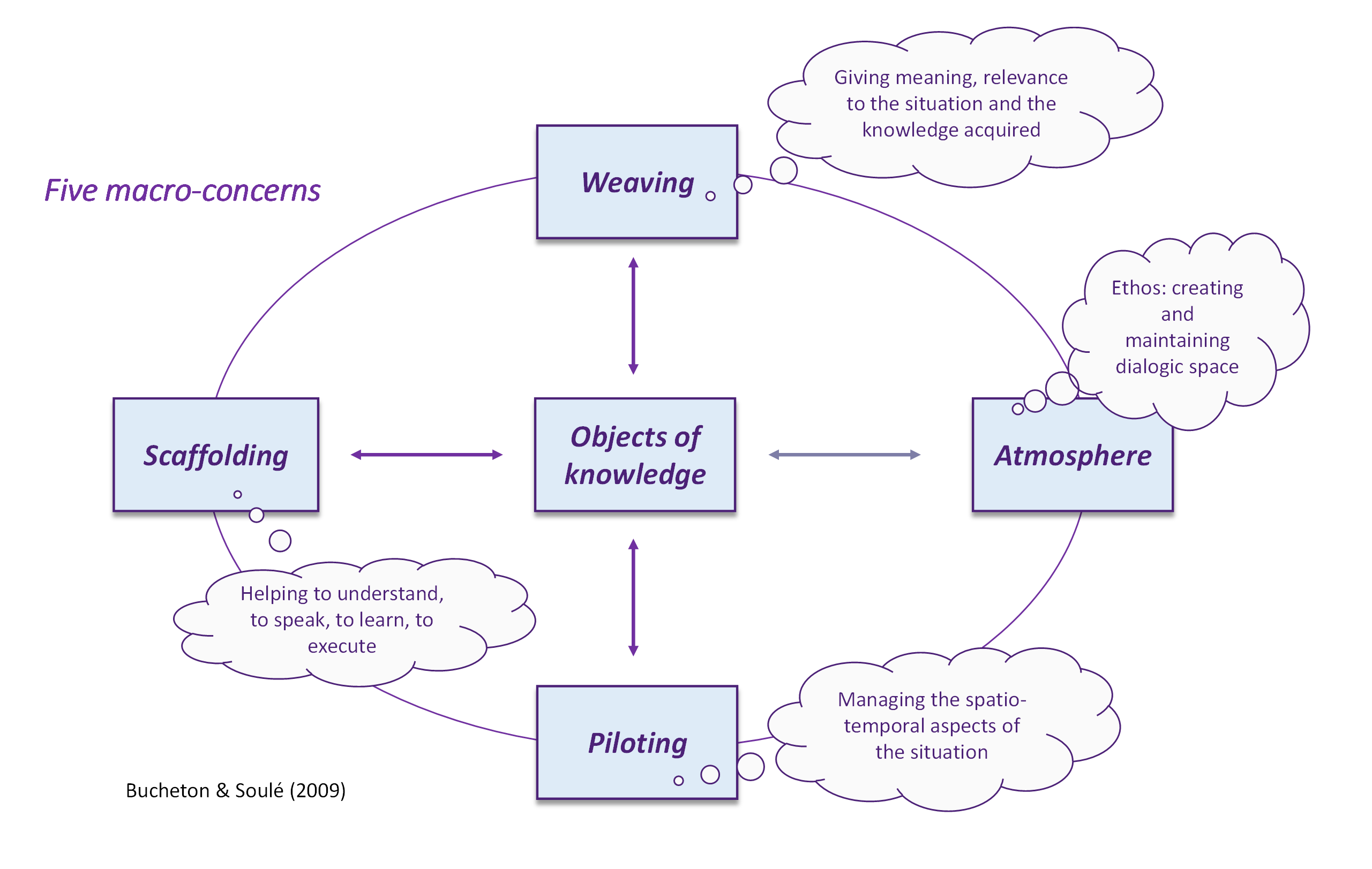

FIGURE 1. Multi-agenda of teaching concerns (adapted from Bucheton & Soulé, 2009)

Bringing to light a pedagogical heritage: an ergo-didactic approach

ANGELIKA GÜSEWELL HEMU – Haute École de Musique, University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland (HES-SO)

RYM VIVIEN University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland (HES-SO)

PASCAL TERRIEN Aix-Marseille University

Born in 1922, Veda Reynolds studied violin at the Curtis Institute of Music with Efrem Zimbalist (from the Russian school of violin playing). After graduating, she was his assistant in the same institution from 1942 to 1961. During the Second World War, she obtained a position with the Philadelphia Orchestra and became assistant concertmaster during the 1958–59 season, a position of unusual responsibility for a woman at that time. Moreover, she held the position of concertmaster in the Philadelphia Grand Opera Company Orchestra. Along with three other members of the Philadelphia Orchestra, she founded the Philadelphia String Quartet. All four musicians left the orchestra in 1966 upon receipt of a residency at the University of Washington. From 1975 to 1977, Veda Reynolds taught at the North Carolina School of the Arts and then at the Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Lyon between 1979 and 1989. After her retirement, she continued to teach as a private tutor. Among her former students are violinists and violists of international renown, such as Renaud Capuçon; David Harrington, first violin of the Kronos Quartet; William de Pasquale, associate concertmaster of the Philadelphia Orchestra; Joseph Silverstein, former concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra; and Michael Tree, violist of the Guarneri String Quartet.

Veda Reynolds seems to have left a profound mark on many of her students. The French violinist Renaud Capuçon, who studied with her between the ages of 10 and 18 years old, explains:

Today, I realise what an incredible opportunity it was to be taught like that. I think she absolutely gave me that … [pauses and hesitates], sometimes I wonder why I am so musically curious, I think I owe her a lot.

Despite these kinds of testimonials — which reflect the deep respect, recognition, and admiration of Veda’s graduates for their teacher — almost no trace of her pedagogical activity has survived, except some scores, handwritten notes, and press articles now archived at the Curtis Institute of Music. What characterized her teaching? Did it differ from the violin pedagogy used in France’s two national conservatories in the 1980s and 1990s? If so, how? These (and similar) questions formed the starting point for this research project.

We will first review which of the various traces left by music teachers of the past may be mobilized to study their pedagogical legacy. We will then introduce the conceptual framework that has allowed us to develop an alternative methodological approach, namely, the ergonomics of the teaching activity (Clot & Faïta, 2000). Next, we will present the results of an empirical study involving six former students of Veda Reynolds, and then finally discuss the implications of these findings for music teaching.

Traces left by great music pedagogues of the past

The teacher-student filiation, the so-called schools (e.g., the Franco-Belgian, German, or Russian schools of violin playing), the genealogy of teaching between distinguished pedagogues of today and those of the past centuries, as well as technical and artistic heritages have always played and continue to play an important role in instrumental music pedagogy, in the construction of artistic identity, and in the biographies of performers, whatever their level or fame. The genealogy of great performers and the history of instrumental music teaching have been the subject of much research, especially with regard to the teaching of the violin. Most of this research is based on written records left by eminent violin pedagogues of the past. Their essays, methods, treatises, and other publications are windows into their ideas about instrumental learning and teaching.1 When first published, these writings were intended for use by interpreters and teachers, but as one generation succeeds another, they fell into the purview of musicologists, didacticians, and epistemologists (e.g., Gutknecht, 2010; Hopfner, 2011; Masin, 2011; Papatzikis, 2008; Penesco, 2000; Rut, 2006; Seifert, 2003; Szabó, 1978; Terrien, 2022; Vaccarini Gallarani, 2010; and Weiskirchner, 2007).

The purpose of treatises and instrumental methods was to document their authors’ pedagogical viewpoints and to spread their teachings. As such, they constitute primary sources. Another form of evidence that may be used to study the pedagogical and didactic approaches of instrument teachers of the past are the writings of their former students. In some cases, autobiographies and correspondence can be very rich in information on students’ points of view and experiences. For instance, an interesting example of the use of such sources is the book Chopin: Pianist and Teacher — As Seen by his Pupils (Eigeldinger, 1979).

Treatises can inform us about the pedagogues’ point of view, while autobiographies and correspondence make it possible to capture their students' experiences. Neither allows studying what we will call the pedagogical heritage of a teacher, that is, traces of teaching that can be found in the pedagogical activity of former students who are now teachers themselves. In fact, to our knowledge, this question has never been empirically examined. The overall question the present research therefore aims to address is whether the impact of a teacher’s pedagogical and didactic practices on the teaching activity of their former students can be reconstructed in order to bring to light the traces of a pedagogical heritage. Two approaches can be envisaged (and possibly combined) to answer this question: on the one hand, to observe some students who have been taught by the same teacher in order to compare their pedagogical gestures or didactics; on the other hand, to interview them on their pedagogical and didactical practices as teachers in turn. The second approach has the advantage of making it possible to capture the background logic that guides professional practice and therefore comprised the focus of the present research.

Ergonomics of teaching

Ergonomics in its broadest sense is the adaptation of working conditions to the individual with a view to optimal effectiveness and well-being.2 Applied to the field of education, ergonomics is the attempt to understand the process leading from the work prescribed to the work achieved. As such, it seeks to “understand how, on the basis of the instructions given, a teacher not only uses, but reshapes the means at his/her disposal to increase both the effectiveness and the efficiency of action” (Amigues, 2003, p. 14). In the field of music education, this would involve studying and attempting to describe how violin teachers in a music school, each in their own way, apply and implement the curriculum, which sets out the objectives to be achieved at different levels of education. What choices do they make, what directions do they take, all the while adjusting to the specific level and difficulties of their students and to the many unforeseen events that arise during the year?

The distinction between the work prescribed and the work achieved has its counterpart in two key concepts of ergonomics, which are the notions of professional genre and style3. Professional genre encompasses the forms of action, the rules, and the gestures shared by a group (i.e., work prescribed). It is an impersonal memory implicitly mobilized during an individual action, “a kind of social divider, a body of shared evaluations that tacitly regulate personal activity” (Clot et al., 2000, p. 2). In this way, genre is a resource for the professional because it can guide individual action in keeping with the norms of the professional community. Individuals emerge from this collective dimension of genre with their personal style, that is, their way of adapting professional gestures to their individual environments (Clot & Faïta, 2000).

The distinction between work prescribed and work achieved leads to two other key concepts of ergonomics: action vs. activity. In general, action results from prescription and therefore refers to what is to be done. Activity, on the other hand, refers to what is actually done. In this sense, activity is subjective in nature and results not from prescription but from the relationship established by the individual “between his or her action and the environment in which it is exercised” (Amigues, 2003, p. 8). Our focus here is on activity. Further, within activity, ergonomists also distinguish the reality of the activity from the activity realized:

What is done, which can be considered as the activity carried out, is never more than the actualisation of one of the activities that can be carried out in the situation in which it is created. … The reality of the activity is also what is not done, what one tries to do without succeeding, what one would have liked or could have done, what one thinks one can do elsewhere. (Clot et al., 2000, p. 2)

To understand the process leading from work prescribed to work achieved, or from professional genre (e.g., teaching the violin) to individual style (e.g., Veda Reynolds’ teaching style), the activity as a whole should be embraced, that is, the activity carried out and the reality of the activity — its realization in terms of both challenges and opportunities.

Teacher Concerns as Indicators of the Reality of the Activity

In recent years, the modelling of the more or less conscious logic behind teachers’ activity (i.e., reality of the activity) has increasingly become the focus of research and publications. In the Anglo-Saxon world, Fuller’s general concern theory provides a widely cited, seminal framework for examining teachers’ concerns (Fuller, 1969). Fuller and Bown (1975) identified three stages of concern through which teachers have to pass in their development: self-concerns (i.e., worries about their ability to perform in the school environment), task concerns (i.e., worries regarding daily teaching routines), and impact concerns (i.e., worries about student outcomes). Two types of research originated from Fuller’s general concern theory. The first type extended the concept of teacher concerns to the context of educational innovation. The second type (which is most germane to the subject of the present paper) has been concerned with understanding the developmental and learning dynamics of both pre-service and in-service teachers (Conway & Clark, 2003; van den Berg, 2002). A certain number of studies on pre-service school music teachers’ concerns were conducted (e.g., Berg & Miksza, 2010; Campbell & Thompson, 2007; Killian et al., 2013; Miksza & Berg, 2013; and Powell, 2014), whereas research taking into account the point of view of prospective instrumental or vocal teachers is rare.

More recently, in the context of French professional didactics, Bucheton and Soulé (2009) proposed another model in which teacher concerns (i.e., préoccupations enseignantes) are not understood as worries, but as teaching strategies, the more or less conscious underlying logic that guides teachers’ activity. Concerns as defined by Bucheton and Soulé are interesting indicators of the reality of the teaching activity: They enable us to know what a teacher tries or plans to do and what a teacher would have liked to do or could have done.

The model includes five central macro-concerns (see Fig. 1). These constants of teaching activity are considered as “the pillars around which ordinary classroom action, professional knowledge, experience and skills are developed” (Bucheton & Soulé, 2009, p. 33). The five components are as follows: (1) piloting, in the sense of managing and “organising the progress of the lesson”; (2) atmosphere, necessary to “maintain a space of work and collaboration,” an intersubjective space where encounters between students and teachers are possible; (3) weaving, which is the giving of meaning and relevance to the knowledge or skills to be acquired by relating them to students’ lives; (4) scaffolding (Bruner, 1983), which designates all forms of assistance that the teacher provides students with to help them do, think, understand, learn, or perform, building from their prior knowledge or skills; and (5) objects of knowledge, which refer to the objectives of the lesson and the content taught (Bucheton & Soulé, 2009, pp. 33–36).

FIGURE 1.

Multi-agenda

of teaching concerns (adapted from Bucheton & Soulé, 2009)

So far, the multi-agenda has only been used to study group teaching-learning situations. However, the authors explain that their model is intended to be non-prescriptive and, above all, evolving. They have selected "a small network of concepts with strong heuristic power that can enable researchers, trainers, trainees and teachers to think and work together on identified problems" (Bucheton & Soulé, 2009, p. 32), an idea that interested us and on which we built the present research.

Aim and research question

As explained in the introduction, the main objective of this research was to bring to light the pedagogical heritage of the famous violinist and teacher Veda Reynolds by analyzing and comparing the discourse of her former students. Setting out towards this initial objective, and taking into account the theoretical elements outlined above, the following research questions were formulated:

Which teaching concerns do former students of Veda Reynolds mention when they are questioned about their own teaching and that of their former professor’s teaching?

Are these concerns shared and specific enough to confirm the hypothesis of the existence of a specific teaching style and thus a pedagogical heritage?

Participants

The first step in recruiting former students of Veda Reynolds was to compile the most complete list possible of the students she had trained during the last twenty years of her teaching career, between 1979 (when she began teaching at the Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Lyon) and 2000 (the year of her death). The second step was to attempt to contact those former students, targeting particularly those who adopted a regular teaching activity — in a school, conservatory, or high school of music, or privately — either in France or in French-speaking Switzerland.4 Of the eight persons on the shortlist thus constituted, six volunteered to take part in the research, two women and four men, whose ages ranged between 32 and 59 years. At the time of the study, all held teaching posts: five in French regional conservatories (non-professional training) and one in a Swiss music university (professional training). All had completed an important part of their violin training with Veda Reynolds, either in private classes or as part of their professional studies (weekly 2- to 3-hour lessons for a period of 4 to 8 years).

Data Collection

For data collection, the self- and cross-confrontation interview method (Clot, 2008; Duboscq & Clot, 2010; Oddone et al., 1981) was used, which gives access to both the visible and hidden sides of an activity. This method places practitioners in front of a video recording of their professional activity and has them comment on their actions, interventions, and concerns, thereby allowing the reality of the activity to emerge. It therefore involves, first, filming the professional (in this case the violin teachers) in action. The commentary is made in the presence of a researcher (simple self-confrontation) or of peers (cross-confrontation). Taking into account the availability of the six participating violin teachers and the willingness of their students (i.e., the prior, informed consent of the schools’ headmasters and the parents of the pupils concerned had to be obtained), dates were set for some members of the research team to travel to the different music schools and conservatories to film half days of teaching.

For organizational reasons, the simple self-confrontation interviews took place several weeks after the video recordings, allowing each participant the time necessary to view their recordings and to select a few excerpts (total duration: a maximum of 30 minutes) that they “would find interesting to discuss with the researchers” (instruction given at the beginning of the interviews). At the same time, the research team also established its own selection of excerpts to complement the teachers’ selections. The aim here was to ensure that the range of video episodes selected covered lessons at different levels, addressing different teaching content (i.e., right- and left-hand technique, general musical knowledge, and performance issues), and was rich in teacher-student interaction.

The simple self-confrontation interviews were all conducted at HEMU – Haute École de Musique (Lausanne, Switzerland), where participants were confronted with three short (3–4 minutes) video sequences in the presence of a member of the research team (as stated, there were two sequences from the participants' choice and one sequence from the team's choice). The instruction given was to watch the video excerpt in its entirety first, without interruption, so as to recall the moment. During a second screening, a few days later, participants could then intervene at any time to pause the video and comment on their teaching activity — on the visible part, the activity realized, but also on the invisible part, the background logic or the reality of the activity. Through the use of questions and requests for clarification, the researcher also led them to develop this second aspect. The simple self-confrontation interviews lasted between 60 and 90 minutes and were themselves filmed with a field of view taking in the researcher, the participant, and the video being viewed and discussed.

For cross-confrontation, two groups of three were formed so that teacher profiles were varied in terms of professional background, training, and age. Three excerpts from those selected by the participants were put forward for discussion; here again, the idea was to cover lessons at different levels and address different teaching content in order to stimulate rich and varied discussion about teaching. The length and modalities of cross-confrontation interviews were the same as for the simple self-confrontation.

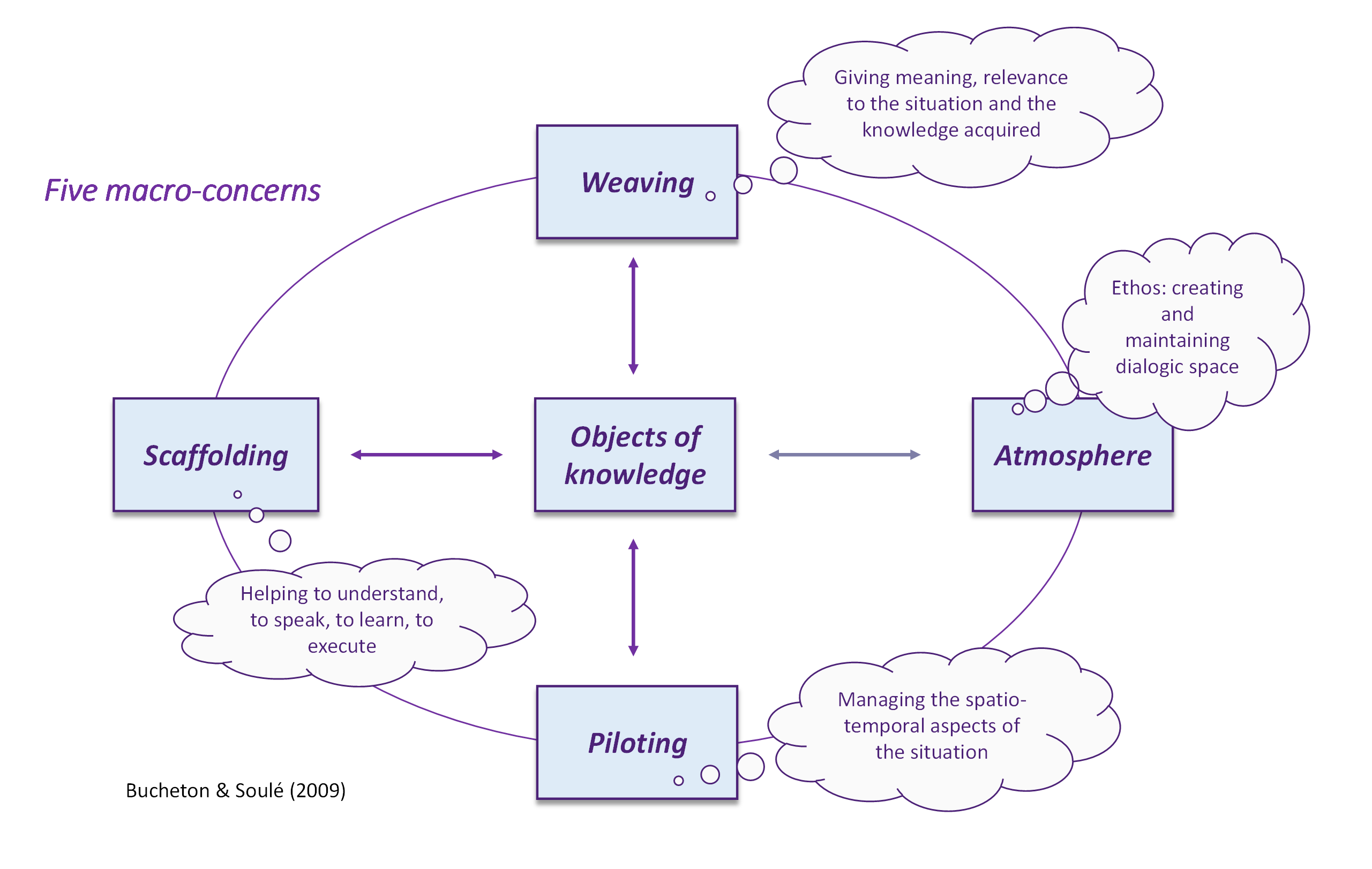

The first step was to transcribe in full all interviews (simple self- and cross-confrontation). Content analysis was then performed using HyperResearch software. The objective of this analysis was to reveal evidence of the teaching concerns. Five categories of a priori codes corresponding to the five macro-concerns of the Bucheton and Soulé (2009) model were established, namely: (1) piloting, (2) atmosphere, (3) weaving, (4) scaffolding, and (5) objects of knowledge. For each of these pre-established categories, an emergent coding was then applied on the basis of the ideas appearing in the discourse and the concepts identified in order to translate macro-concerns into micro-concerns. Given that the list of micro-concerns was developed during the coding process and not a priori, an iterative process of code definition and code application was necessary to establish a stable grid (see Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Stable

coding grid, macro- and micro-concerns

The initial coding of the interviews was then reviewed in light of this stable grid, and the utterances referring to ‘Reynolds’ teaching’ were distinguished from the utterances referring to the teaching of one of her students (‘own teaching’). A final count was then performed encompassing each of the five a priori categories and each of the emergent codes. This process aimed to determine — within both ‘own teaching’ and ‘Reynolds’ teaching’ — the proportion of discourse each teacher dedicated to each concern.

Results

The first analysis involved plotting the proportion of encoded utterances for each of the five concerns of the teacher multi-agenda model (Bucheton & Soulé, 2009), presenting them separately for the six participants in the form of radar graphs.5 The shape (or spider's web) that unfolds between the five axes of these radar graphs shows the proportion (in %) of total codings (i.e., 100%) attributed to each of the five concerns, which is an indicator of the relative importance the participants attach to them. This resulted in two series of plots: one plotting references made by Reynolds’ former students in relation to their own teaching activity, and another plotting their references to Reynolds’ activity. The assumption was that similar forms (or spider's webs) reflect similar teaching priorities, strategies, or styles, which in turn could bring to light the pedagogical legacy of Veda Reynolds.

This quantitative analysis was then linked to quotes that illustrate the expression of the concerns identified in their work with students. The second analysis compared whether the concerns expressed by Reynolds’ former students in relation to their own activity corresponded to those they assumed to characterize Reynolds’ teaching. This comparison aimed to shed light on the existence or otherwise of the Reynolds’ style in the form of a particular variation of the professional genre of the violin teacher. Finally, analysis was performed on the pedagogical gesture that appeared to be central to Reynolds’ teaching: exploring with the student.

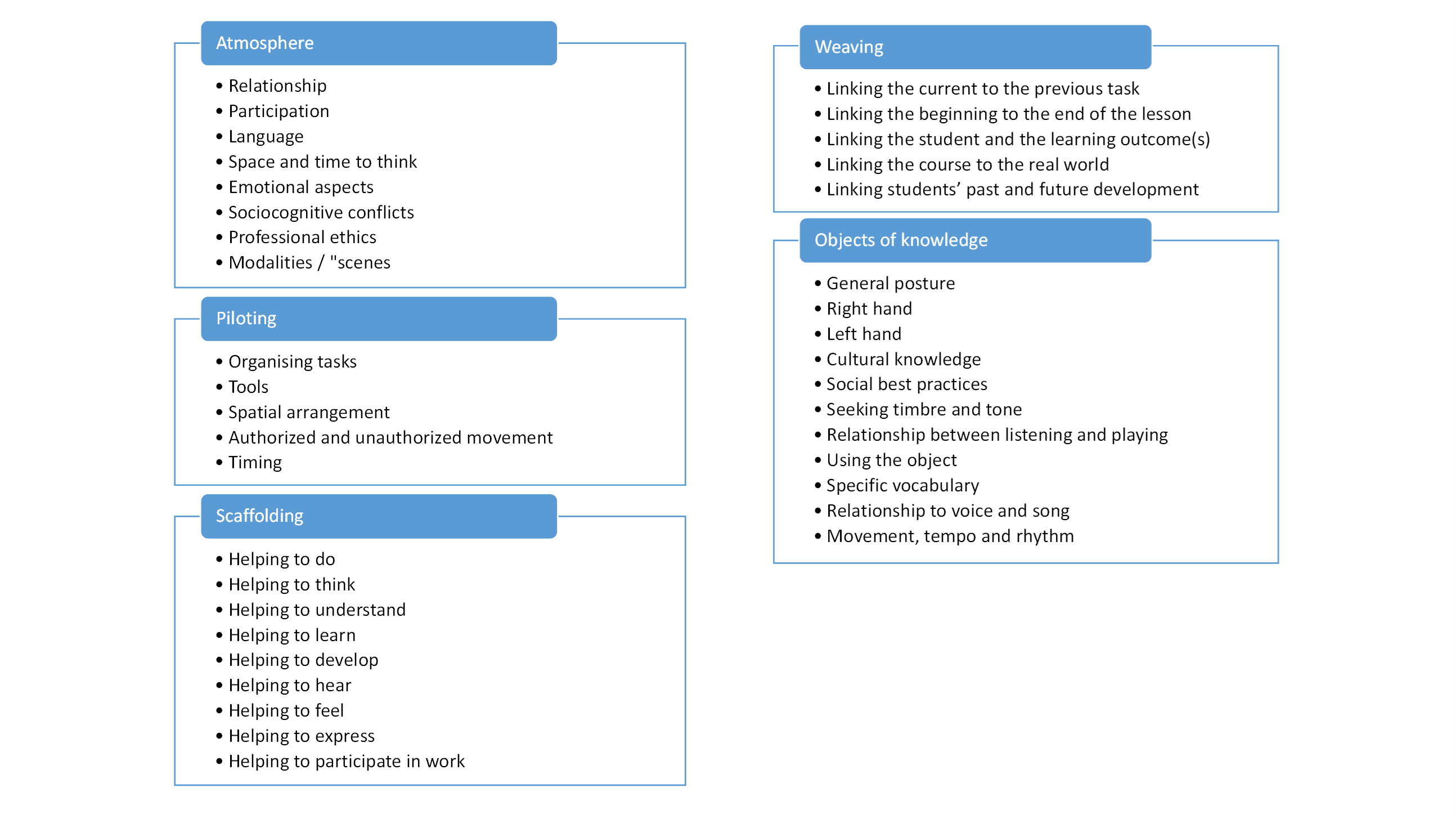

Own Teaching

The radar graphs plotting teacher discourse on ‘own teaching’ (Fig. 3) highlight that the concern ‘scaffolding’ seems to be at the heart of the concerns of all participants (22–26% of codings), followed by ‘objects of knowledge’ (19–26%) for five of six (Hannah, Jenny, John, Ralph, and René6) and ‘atmosphere’ (25%) for the sixth (Frederik). ‘Piloting’ (14–18%) and ‘weaving’ (18–20%) account for a smaller proportion of the discourse.

The six teachers talked extensively about what they do during violin lessons to help their students develop their violin and musical skills. The most frequent reference was to ‘make … feel’ (i.e., make the student feel), often raised in connection with other forms of scaffolding, in particular ‘make [the student] hear.’ For example, Jenny recalled the importance of establishing a link between what the student feels and what they hear: “Feeling and listening really apply to practice. As soon as a motion stops, it no longer resonates.”

According to the participants, ‘make … feel’ always precedes ‘instilling understanding’ in their practice. For example, Hannah explained that she systematically starts by making the student feel a movement before providing the corresponding technical explanation: “At the outset, I refrain from discussing wrist movement, as I’m trying to make him feel it first.”

FIGURE 3.

Proportion

of ‘own teaching’ discourse representing the concerns of the

teacher (based on the multi-agenda model of Bucheton and Soulé,

2009)

A similar approach was described by Ralph in saying that “feeling is everything” and that “mainly with children, one has to prefer terms relating to the senses than to the intellect.” Ultimately, ‘make … feel’ allows the teacher to put themselves in the student's skin or body to get an idea of their experience and sensations. For example, René explained that he systematically requests his students show him on his own finger how they hold the bow:

How else can you know how someone holds his or her bow? There is no other way, there’s no device to measure it [pause] so, provided the student isn’t cheating too much, he’s going to transcribe on your finger how he is on the bow, and that's like a thermometer.

The specific objects of knowledge referred to in interviews were above all ‘the body and general posture’ (17% of encoded utterances), followed by ‘seeking timbre and tone’ (17%) and ‘attention paid to the right hand’ (14%). It should be noted that these objects of knowledge are directly related to the two preferred modes of scaffolding: make students feel and hear.

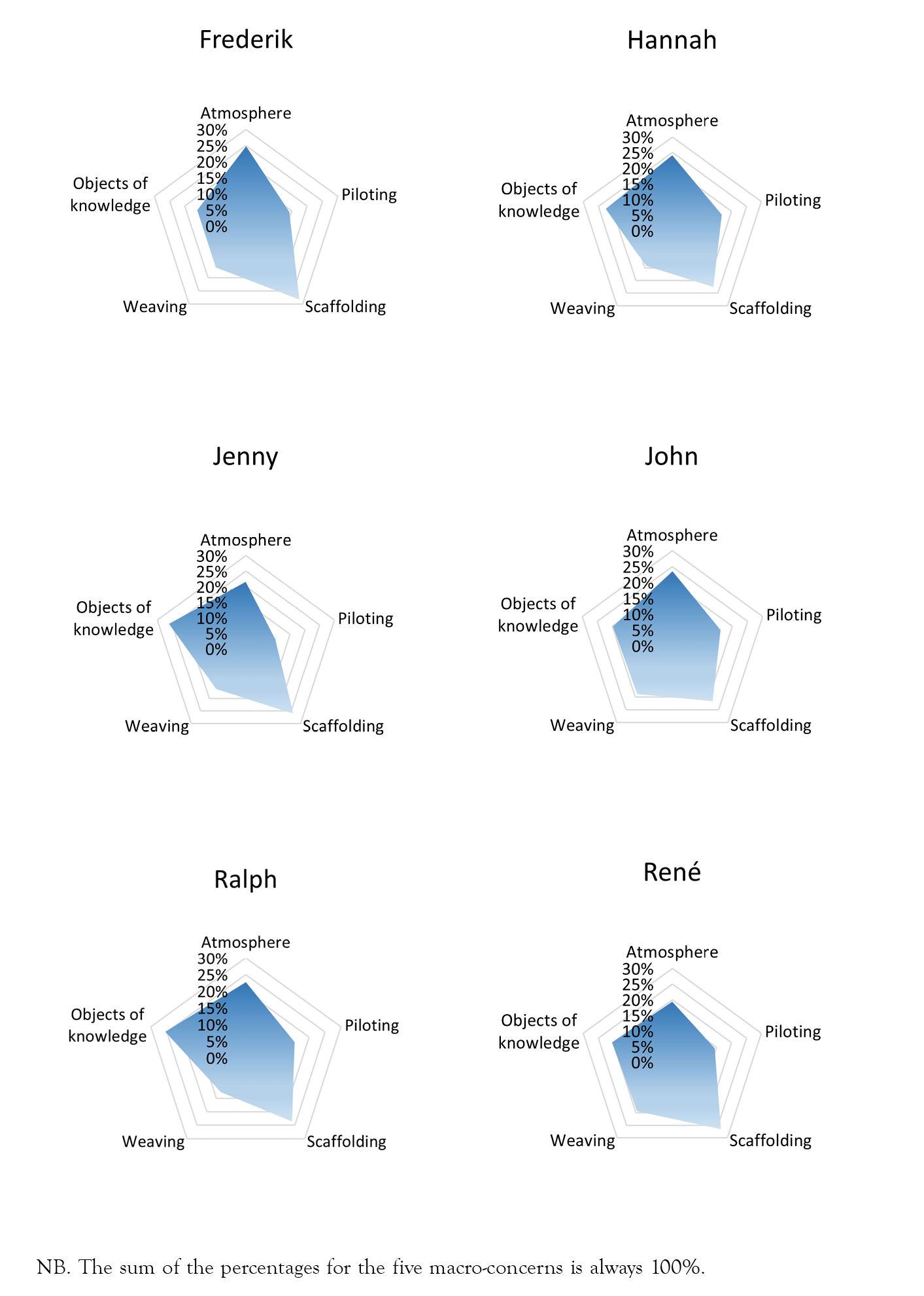

Reynolds’ Teaching

The charts representing the discourse on ‘Reynolds’ teaching’ (Fig. 4) show the proportion of codings referring to ‘scaffolding’ (23–28%), ‘atmosphere’ (22–25%), and ‘objects of knowledge’ (16–26%) to be higher than the proportion of codings that concern ‘piloting’ (10–17%) or ‘weaving’ (13–19%).

Once more, ‘make … feel’ seems to be central in supporting student learning. René explained how Reynolds systematically encouraged her students to experiment in order to find “the physical sensation of the gesture perfectly suited to the music.” John reported how Reynolds would “first work on posture, without the instrument, in an attempt to feel and find the right position and the right balance. She would then insert the violin, trying not to upset the balance.” Likewise, Hannah described Reynolds as being attentive to the particularities of each one, facilitating an understanding and a feeling of them in order to integrate them into their way of playing:

In each student, there was a kind of problem to solve; she was very attentive to everyone’s morphology; she made them see how their hands hung naturally, to feel things, so that nothing would be unnatural. It was fundamental for her.

FIGURE 4.

Proportion

of ‘Reynolds’ teaching’ discourse referring to the concerns of

the teacher multi-agenda model of Bucheton and Soulé (2009)

This illustrates that, for Reynolds, ‘make … feel’ would always involve taking into account the physiological realities and limitations of her students. For example, John reported that Veda “was interested by everyone, regardless of their skills and faculties; everyone’s individual concerns were of interest to her. She would say, for example, ‘Your hand is slight, so let’s find solutions that suit it.’” With regard to the teaching contents or knowledge objects most often mentioned by the six participants when talking about their former teacher’s classes, the conspicuous interest in ‘the body and general posture’ (20% of codings) appears first, followed by ‘seeking timbre and tone’ (14%) and ‘attention paid to the right hand’ (12%).

According to René, posture was the foundation of Reynolds’ teaching:

Her starting point was really explaining that you have to be anchored to the ground. In other words, as if both your feet were trees, and she would push me and say, “on the whole, if you’re well anchored to the ground and your pelvis is tilted slightly forward, you should rock backward and forward without falling over.” … And it’s about your feeling.

Jenny recalled that Reynolds would sometimes ask her students to focus on their bodily sensations in relation to a given bow stroke: “Through this exercise, she wanted to make them aware of what they are doing, of any parasitic movement and of the unity of the body.” Regarding the right hand, René explained that Reynolds would ask her students to “completely relax their right arm to comprehend its weight and at the same time to release any tension.” Finally, Frederik reported that in Reynolds’ classes, her students “tried and tested things, sought relaxation to achieve a better sound before trying to reproduce the same sound by focusing on the ear and attempting to regain the sensations.”

Comparisons

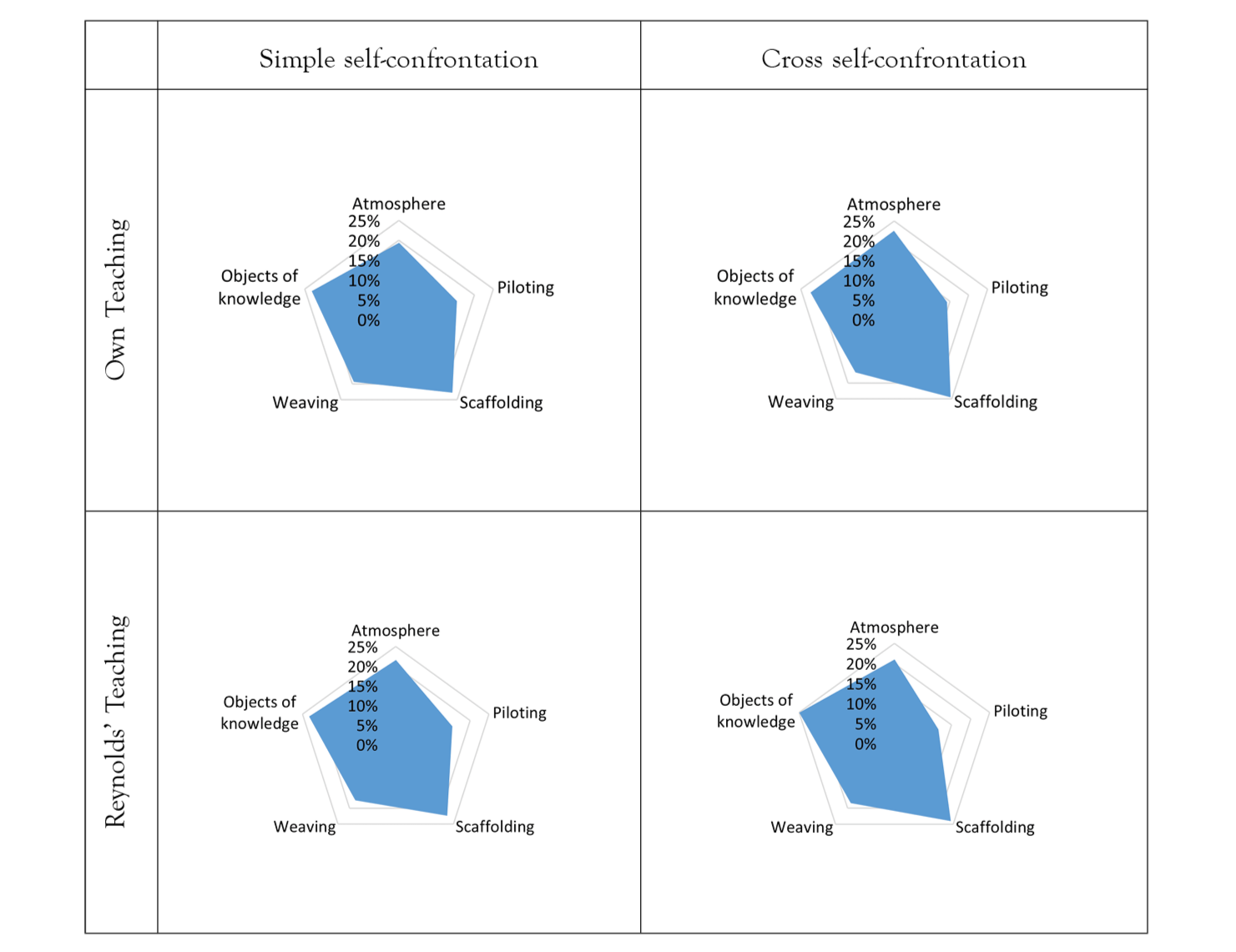

The data was then aggregated and averaged to facilitate comparison between the importance Reynolds’ former students attached to each macro-concern with reference to ‘own teaching’ and to ‘Reynolds’ teaching.’ This analysis was performed separately for the simple and cross self-confrontation interviews and resulted in the four charts presented in Fig. 5. All charts show a similar profile, with significantly higher percentages of codings referring to ‘scaffolding,’ ‘objects of knowledge,’ and ‘atmosphere’ (19–25%) than to ‘weaving’ and ‘piloting’ (12–19%). This graphical analysis also reveals a more balanced distribution in the proportion of discourse dedicated to the five concerns of the Bucheton and Soulé (2009) model when referring to ‘own teaching’ than when referring to ‘Reynolds’ teaching.’

FIGURE 5.

Proportion

of ‘own teaching’ and ‘Reynolds’ teaching’ discourse in

simple and cross self-confrontation interviews

Searching With the Student: A Central Pedagogical Gesture

In the discourse of Reynolds’ former students about her teaching, one idea came up repeatedly: searching. The process of searching, or being in search, seems to have been a basic principle and central element of Reynolds’ pedagogy. Her former students all talked about this process of exploration, which took a prominent place in the classes: “It took hours! Sometimes we would spend half an hour on one shift” (René). That process also involved the student in every instance: “She would try to do it with us and to explore. For that matter, she would even explore out loud sometimes” (Ralph). The trigger for search was usually a problem or difficulty that had to be analyzed in all its detail in order to understand its cause: “So here I remember Veda Reynolds exploring, there had been a difficulty or something that hadn’t sounded right, given that in this case the resulting sound was unconvincing [pause] we sought the cause. The cause, literally, the underlying cause!” (Ralph). As part of her in-depth analysis, it was not enough for Reynolds only to observe her students and to accompany them in their thought processes, but she would often also touch them: “I remember that she looked at us a lot, I mean, really a lot, and that she would also [guide us with her hands]” (Frederik). Moreover, during her classes, she would even sometimes analyze her own practice in order to understand how she herself did it. To bear this out, she would use a mirror. “We’d stand in front of the mirror and, uh, she explored. She would try to understand inside of her whatever was going on” (Frederik). According to the participants, Reynolds was always open to alternative solutions and curious to discover other approaches and practices as sources of inspiration:

And, in fact, this is also the key to her teaching, I believe. Seeking to try to understand what someone is saying or doing. Sometimes she would say, “I listened to someone play, it was interesting, he does something,” then she spent hours exploring before saying, “That’s odd, why does he do that?” (René)

Having identified the cause of the problem or difficulty, her goal was then to find personalized solutions that would “really adapt to the person” (Ralph). There was never any standard solution, a one size fits all. “There were no, uh, recipes” (Frederik). “What she sought a lot was the exact placing for the precise passage, for that person” (Ralph). Reynolds was never satisfied with the first idea that came to mind; she always kept on looking for ways to do even better, until she struck the best: “We were exploring until [pause] so, in fact, we were trying to find what was best for the student, I’d say!” (Frederik). The pursuit was always guided by a musical idea:

It was really the pursuit of the right gesture, so the end result would be the best match for the desired musical rendering. … We really analysed a phrase, the placing of the bow, the right draw speed, the fingering too, so as to find definitively the phrasing sought. (René)

Reynolds would explore with her students, but she also encouraged them to explore on their own, guiding them towards autonomy. “She helped me to search a lot” (Jenny). In this way, she led them to develop their own solutions and strategies:

What I found great about her was that she encouraged us to explore for ourselves. … That’s to say, she was never, uh, “Well, look, you’re going to do this or that” [pause], and that’s how I ended up playing intermittently without a cushion,7 I brought small pieces of materials; she told me, “Explore for yourself, make your own little cushion.” There were some of us who had big cushions, I mean, that’s to say, according to their morphology, everyone had to find. (John)

According to René,

that was the key to her teaching! For every fingering8 that she proposed, there were always two or three solutions! There was never, she never imposed a fingering because she knew full well that a fingering that worked for her might not work for us, she gave different options, she said, “Explore!”, so she encouraged constant reflection, which is still quite exceptional.

As conceived by Reynolds, the practice of exploring left room for experimentation and was always free of judgement:

She gave me the courage to perform certain gestures, and then she would sort through them, more or less into “what was appropriate” and “what was less so.” We dared to try a lot. And that’s huge. Because we weren’t afraid to get it wrong. We would say to ourselves, “Well, hey, I’ll give it a try, maybe it’ll work, maybe it won’t.” And that, for me — of course, someone else might not have had the same feeling — but for me, this is part of the Veda Reynolds heritage, to be at ease with there not being good things, bad things, sacred things, unrefined things. We pursue something, and then we improve, we try to improve and [hesitates] and then that’s it, that’s life! (Hannah)

Discussion

This research project aimed to bring Veda Reynolds’ pedagogical heritage to light by identifying common traces of her teaching style in the discourse of six of her former students as they reflected on their own teaching activity. For this purpose, video recordings were made of three or four classes given by her former students, who later participated in simple and cross self-confrontation interviews. The quantitative analysis of these interviews revealed the relative importance the participants attached to each of the five macro-concerns of the Bucheton and Soulé (2009) model when talking about their own teaching activity and that of Reynolds. ‘Scaffolding,’ ‘objects of knowledge,’ and ‘atmosphere’ occupied a larger part of the discourse than ‘weaving’ and ‘piloting,’ suggesting a focus on student- and content-centred teaching, which aims to make the pupil an autonomous actor in their own learning. The qualitative analysis, in turn, highlighted that ‘make … feel,’ appearing often in combination with ‘make … hear,’ is central to the ‘scaffolding’ concern shared by Reynolds’ former students, generally preceding ‘instilling understanding’ and, above all, allowing to link a gesture to an intended sound result.

There is a similarity between (a) the importance that Reynolds’ former students seem to attach to the five macro-concerns of the Bucheton and Soulé (2009) model in their own teaching and (b) the place that these concerns occupy in their discourse on Reynolds’ teaching. This similarity corroborates the hypothesis of a Veda Reynolds’ pedagogical legacy, and it provides information on what might have made Reynolds’ teaching specific and particular to her. Added to this characteristic profile of concerns is a pedagogical gesture that seems to have been central to Reynolds’ approach of pedagogy, namely, searching with the student. This gesture may be described as crosscutting, as it is linked as much to ‘scaffolding’ as it is to ‘objects of knowledge’ and ‘atmosphere.’ It appears repeatedly in the discourse of her participating former students, seemingly having left a deep impression upon them all.

In the light of these observations, it is plausible to suppose the existence of a particular variation of the professional genre of the violin teacher, a specific “way of adapting professional gestures to the individual environment” (Clot & Faïta, 2000), in other words, a “Veda Reynolds style.” The methodology of self-confrontation interviews in articulation with an analytical grid developed from the model of Bucheton and Soulé (2009) shed light on the participants’ reflections and therefore on their reality of the activity or background logic. Based on an in-depth discussion of the activity realized by both researchers and participating violin teachers, the ergo-didactic approach (Espinassy & Terrien, 2018) allowed the gap to be overcome that may exist between what instrument teachers say and plan to do, and what they actually do (Koopman et al., 2007).

Analyzing instrumental music teachers’ preoccupations (i.e., reality of the activity) seems promising not only for research purposes, but also for improving initial and continuing training (of pre-service and in-service teachers). Indeed, it is established that “teachers’ beliefs and attitudes … are closely linked to their strategies for coping with challenges in their daily professional life and to their general well-being and [that] they shape students’ learning environment and influence student motivation and achievement” (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2009, p. 89). At the beginning of the 1990s, Pajares (1992), a pioneer in research on teacher beliefs (the English concept that seems to come closest to the French préoccupations enseignantes9), held that “understanding the belief structures of teachers and teacher candidates is essential to improving their professional preparation and teaching” (p. 307). More recently, Woody et al. (2018) have been claiming that

similar to findings in the fields of business, health care, and general education, research in music education has indicated that teachers who reflect on critical incidents in their past musical experiences and teaching activities gain important insights into their own beliefs and assumptions that underpin their classroom practices. (p. 112)

The ergo-didactic methodology used within the scope of the present research might well be an interesting tool to further experiment within music teacher education. Indeed, it appears that the six teachers who participated in the Veda research, while summoning their professor's memory, found themselves questioning and interpreting their practice, reflecting on their professional identity, and even imagining other ways of doing things (Vivien et al., 2021). The cross-confrontation interviews best contributed to this shift in thinking. Such shifts would be well worth extensive experimentation, possibly in combination with look-alike instructions (i.e., instruction au sosie; Miossec, 2017).10

There is no empirically established professional genre of either the instrument teacher or the violin teacher from which the Reynolds’ style would stand out as a subcategory or variant. Although there does seem to be an implicit agreement among teachers on what characterizes and underpins their professional activity, this supposed shared understanding has never been put to the test of an ergonomic study. Further research should therefore be carried out with violin teachers of as diverse an age, education, and professional profile as possible in order to establish what constitutes the

implied part of [their] activity, what [they] know and see, expect and recognise, appreciate or fear; what is common to them and unites them under real-life conditions; what they know they must do thanks to a community of presupposed evaluations, without it being necessary to specify the task each time it arises. (Clot & Faïta, 2000, p. 11)

There is also an historical dimension to our questioning that must be taken into account. Professional genre is evolving: What is in the air and seems obvious today (i.e., involving individual students and making them actors in their own learning) was not a common approach in French conservatories during the 1980s and 1990s. It is therefore legitimate to ask whether the deep impact of Veda's teaching on her students was driven primarily by her pedagogy being ahead of its time. Could it be that the great contrast among her way of transmitting the art of playing the violin, her conception of the pedagogical relationship, and her students’ past and/or ongoing, parallel experience with other teachers goes — at least in some way — towards explaining her aura? It is also legitimate to raise the question of whether it is still possible to distinguish what has been highlighted as the Veda style from what constitutes the violin teacher genre today, considering the general shift in pedagogical focus away from technique and towards the teacher-student relationship. These reflections neither call into question the relevance and interest of studying the pedagogical legacy of great music pedagogues nor of developing corresponding research tools; quite to the contrary, they draw attention to the methodological issues and challenges involved in studying the past from a contemporary perspective.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the six violin teachers who took part in the project for generously sharing their experiences and making their time available. We are also grateful to HES-SO, HEMU – Haute École de Musique, and Aix-Marseille University for their financial support.

notes

Francesco Geminiani (1751); Léopold Mozart (1756); Pietro Signoretti (1777); Baillot, Kreutzer & Rhode (1793); Louis Spohr (1832); Jacques-Féréol Mazas (1832); Jean Delphin Alard (1848); Joseph Joachim (1905); Carl Flesch (1911); Ivan Galamian (1962); and Yehudi Menuhin (1971) or Robert Gerle (1983/1991), to name a few.

See the definitions (in French only) of the Société d’Ergonomie de Langue Française https://ergonomie-self.org/lergonomie/definitions-tendances/

Not to be confused with the notions of genre (i.e., categorization of music, such as rock, rap, jazz, or classical music) and style (i.e., the set of characteristics that are specific to a composer, an era, an aesthetic trend, a way of performing, a mode of instrumental playing, etc., and that distinguish them from others) as used in the music context.

The option of contacting and including violin teachers residing and teaching in the United Kingdom, in Canada, or the United States was ruled out for practical reasons: Travelling outside Switzerland or France to film lessons and interview teachers in English (also involving translation for inclusion in the data set) would have far exceeded the resources allocated to the project.

Also known as: Kiviat diagram, star plot, and spider or web chart.

To preserve confidentiality, teachers' names have been replaced by pseudonyms.

The cushion is an accessory that is placed under the violin so that the instrument is stable in a horizontal plane and supported without any effort needed from the left hand. Originally, it was made of foam and fixed either to the endpin or by elastic bands on the F-holes of the violin. Today, it is generally a wavy, rigid, and fleecy bar that runs across the entire back of the violin and closely hugs the violinist’s collar bone. There are also inflatable cushions allowing for adjustable thickness.

Violinists often talk about fingering also in terms of the left-hand position, that is, the general placement of the left hand required to play a given note on a certain string, using a certain finger.

Kagan (1992) noted that “the term ‘teacher belief’ is not used consistently, with some researchers referring instead to teachers’ ‘principles of practice,’ ‘personal epistemologies,’ ‘perspectives,’ ‘practical knowledge’ or ‘orientations’” (p. 66).

Look-alike instruction is a method of putting lived experience into words. It is a type of interview in which a person (instructor) gives instructions for the lookalike to act as they do.

References

Alin, C. (2010). Le geste formation : Gestes professionnels et analyse des pratiques. L’Harmattan.

Amigues, R. (2003). Pour une approche ergonomique de l’activité enseignante. Skholê, 1, 5–16.

Berg, M. H., & Miksza, P. (2010). An investigation of preservice music teacher development and concerns. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 20(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083710363237

Bruner, J. S. (1983). Le développement de l’enfant : Savoir faire, savoir dire. Presses universitaires de France.

Bucheton, D. (Ed.). (2009). L’agir enseignant : Des gestes professionnels ajustés. Octarès.

Bucheton, D., & Soulé, Y. (2009). Les gestes professionnels et le jeu des postures de l’enseignant dans la classe : Un multi-agenda de préoccupations enchâssées. Education et didactique, 3(3), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.4000/educationdidactique.543

Campbell, M. R., Thompson, L. K. (2007). Perceived concerns of preservice music education teachers: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Research in Music Education, 55(2), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/002242940705500206

Clot, Y. (2008). Le travail sans l’homme ? Pour une psychologie des milieux de travail et de vie. La Découverte.

Clot, Y., & Faïta, D. (2000). Genre et style en analyse du travail : Concepts et méthodes. Travailler, 4, 7–42.

Clot, Y., Faïta, D., Fernandez, G., & Scheller, L. (2000). Entretiens en autoconfrontation croisée : Une méthode en clinique de l’activité. Perspectives interdisciplinaires sur le travail et la santé, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.4000/pistes.3833

Conway, P. F., & Clark, C. M. (2003). The journey inward and outward: A re-examination of Fuller’s concerns-based model of teacher development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(5), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(03)00046-5

Duboscq, J., & Clot, Y. (2010). L'autoconfrontation croisée comme instrument d'action au travers du dialogue : Objets, adresses et gestes renouvelés. Revue d'anthropologie des connaissances, 4(2), 255–286. https://doi.org/10.3917/rac.010.0255

Eigeldinger, J. J. (1979). Chopin vu par ses élèves : Textes recueillis et commentés. La Baconnière.

Espinassy, L., & Terrien, P. (2018). Une approche ergo-didactique des enseignements artistiques, en éducation musicale et arts plastiques. eJRIEPS, 1, 23–42. https://doi.org/10.4000/ejrieps.293

Fuller, F. F. (1969). Concerns of teachers: A developmental conceptualization. American Educational Research Journal, 6(2), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312006002207

Fuller, F. F., & Bown, O. H. (1975). Becoming a teacher. In K. Ryan (Ed.), Teacher education: The 74th yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, part 2 (pp. 25–52). University of Chicago Press.

Gutknecht, D. (2010). Der italienische Violinstil der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts als Grundlage von Technik und Ästhetik der französischen Geigerschule zu Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts [The Italian violin style of the second half of the 18th century as the basis of technique and aesthetics of the French violin school at the beginning of the 19th century]. In P. Kuret (Ed.), The Mediterranean: Source of music and longing of European Romanticism and Modernism (pp. 92–99). Festival Ljubljana.

Hopfner, R. (2011). Die Geige: Spiel, Technik und Pädagogik in Wien [The violin: Playing, technique and pedagogy in Vienna]. In S. Haag (Ed.), “Der Himmel hängt voller Geigen”: Die Violine in Biedermeier und Romantik. Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien.

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Implications of research on teacher belief. Educational Psychologist, 27(1), 65–90. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2701_6

Killian, J. N., Dye, K. G., & Wayman, J. B. (2013). Music student teachers: Pre-student teaching concerns and post-student teaching perceptions over a 5-year period. Journal of Research in Music Education, 61(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429412474314

Koopman, C., Smit, N., de Vugt, A., Deneer, P., & den Ouden, J. (2007). Focus on practice-relationships between lessons on the primary instrument and individual practice in conservatoire education. Music Education Research, 9(3), 373–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800701587738

Masin, G. (2011). Violin teaching in the new millennium: In search of the lost instructions of great masters — An examination of similarities and differences between schools of playing and how these have evolved, or: Remembering the future of violin performance [Doctoral thesis, Trinity College Dublin]. Trinity’s Access to Research Archive. http://www.tara.tcd.ie/handle/2262/64557

Miksza, P., & Berg, M. H. (2013). A longitudinal study of preservice music teacher development: Application and advancement of the Fuller and Bown teacher-concerns model. Journal of Research in Music Education, 61(1), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429412473606

Miossec, Y. (2017). Donner des consignes à un sosie et adopter un autre regard sur les possibilités de développement des manières d’agir au travail : Eléments de réflexion à partir d’une intervention en santé au travail. Horizontes, 35(3), 38–57. https://doi.org/10.24933/horizontes.v35i3.552

Oddone, I., Re, A., & Briante, G. (1981). Redécouvrir l’expérience ouvrière : Vers une psychologie du travail ? Éditions sociales.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2009). Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Environments: First Results from TALIS. OECD Publications. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264068780-en

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers' beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307

Papatzikis, E. (2008). A conceptual analysis of Otakar Ševčík’s method: A cognitive approach to violin teaching and learning [Doctoral thesis, University of East Anglia]. UEA Digital Repository. https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/id/eprint/47264/

Penesco, A. (2000). L’univers violonistique des années trente. In D. Pistone (Ed.), Musiques et musiciens à Paris dans les années trente. Honoré Champion.

Powell, S. R. (2014). Examining preservice music teacher concerns in peer- and field-teaching settings. Journal of Research in Music Education, 61(4), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429413508408

Rut, M. (2006). The influence of the Franco-Belgian violin school on violin didactics in Poland from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century. Revue belge de musicologie/Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Muziekwetenschap, 60, 131–140.

Seifert, R. (2003). Von Ševčík bis Galamian: Zur Entwicklung des Violinspiels im 20. Jahrhundert [From Ševčík to Galamian: On the development of violin playing in the 20th century]. Das Orchester, 51(4), 8–18.

Szabó, Z. (1978). The violin method of B. Campagnoli: An analysis and evaluation [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Indiana University.

Terrien, P. (2022). Une histoire de l’enseignement du violon en France à travers ses méthodes. In C. Fritz & S. Moraly (Eds.), Le violon en France du XIXe siècle à nos jours (pp. 105–131). Sorbonne Université Presses.

Vaccarini Gallarani, M. (2010). La scuola violinistica di Alessandro Rolla nei primi anni del Conservatorio di Milano [Alessandro Rolla's violin school in the early years of the Milan Conservatory]. In Mariateresa Dellaborra (Ed.), Alessandro Rolla: Un caposcuola dell’arte violinistica lombarda (pp. 209–219). Libreria Musicale Italiana.

van den Berg, R. (2002). Teachers’ meanings regarding educational practice. Review of Educational Research, 72(4), 577–625. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543072004577

Vivien, R., Güsewell, A., & Terrien, P. (2021). La clinique de l'activité comme méthodologie de recherche et comme vecteur d’innovation pédagogique dans le contexte de l'enseignement instrumental. Recherche en éducation musicale, 36, 1–23.

Weiskirchner, S. (2007). Leopold Mozart and the tradition of Salzburg violin pedagogy: Violin methods and their use in the Salzburg area [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Universität Mozarteum Salzburg.

Woody, R. H., Gilbert, D., & Laird, L. A. (2018). Music teacher dispositions: Self-appraisals and values of university music students. Journal of Research in Music Education, 66(1), 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429418757220