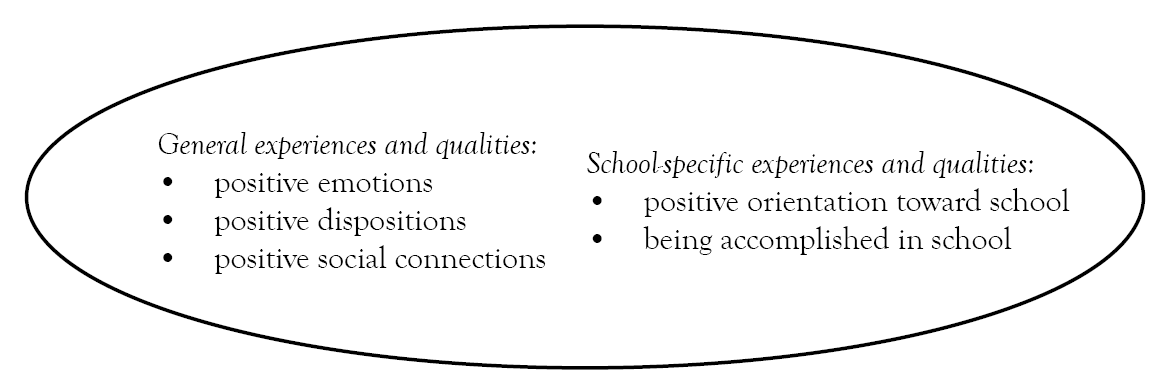

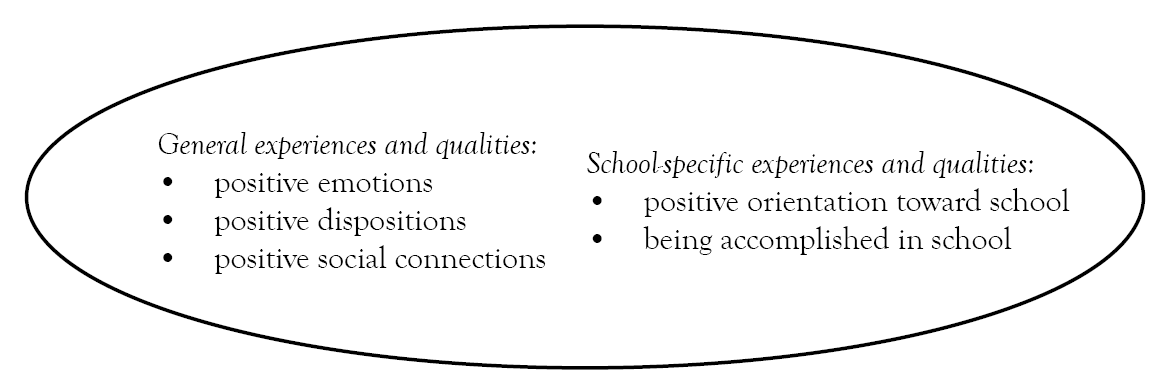

FIGURE 1. Conceptualizing student well-being

STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF STUDENT WELL-BEING: A CASE STUDY

THOMAS FALKENBERG, GRACE UKASOANYA & HEATHER KREPSKI University of Manitoba

There is no shortage of literature on human well-being. One insight we gleaned from this literature is that well-being remains a highly contested concept (Crisp, 2013; Falkenberg, 2014). And while theoretical and empirical work has increasingly begun to distinguish between child well-being and adult well-being (Bagattini & Macleod, 2015; Ben-Arieh, 2008; James et al., 1998), it is now recognized, for instance, that children, as compared with adults, have special capacities for play, imagination, and inquiry (Gheaus, 2018), which likely makes their well-being feel different. Such findings mean that adults can surely provide children with opportunities for accessing certain domains of well-being that were not previously considered important (Gheaus, 2015; Tomlin, 2018). However, with the ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), children’s codified rights to basic welfare and security have been expanded to include participation rights (Lundy, 2014). Article 12 of the CRC states that children have the right to be consulted and have their voices heard in matters that affect them, and most school matters affect children.

We thus take as a starting point for our study that (a) the process of schooling should include children’s well-being as a central aim and (b) students’ own views on their well-being need to be heard and understood. What once might have appeared as a radical idea, student well-being can now be found as a formal goal for public K-12 education across different provinces within Canada (Alberta Education, 2009; Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014). By directly asking students how they understand their well-being in school, we are given first-hand accounts of how well-being is experienced and understood by students. This emerging literature builds on a long tradition of inquiry focusing on student voice: students’ perspectives on school matters (Cook-Sather, 2009; Rudduck & Demetriou, 2003; Smyth, 2007) as well as on school reform (Rudduck, 2007; Wilson & Corbett, 2001). We return to this literature in our conclusion. The motivation for our research is similar. We proceed with the belief that children are the best informants on what the child’s world at school is like, for children.

THE RESEARCH PROBLEM

Respecting the ideas, thoughts, opinions, and preferences of children requires that adults listen and respond to student voices. Although experiences are unique to each person and thus vary among children, the tendency to cluster a group of humans into a distinct class — “children” — suggests that we think of childhood as being distinct from adulthood (Falkenberg & Krepski, 2020). In light of the difference between children and adults in both circumstance (e.g., social positioning) and subjective experience (e.g., developmental stage), we think that children are the best — though not the only — informants on what makes their lives in school go well. In this section, we outline key ethical and practical reasons to take children’s views about schooling into account. Next, we report on the findings from relevant studies that explore children’s views on their own well-being. Lastly, we outline findings on student well-being in schools.

Children’s understandings about their own well-being are significant from both an ethical and practical standpoint. Children are humans with moral, political, and legal rights to well-being, which includes their right to participate in decisions that affect them. Adults therefore have a duty to include children in decisions about their own well-being and to act in the best interests of the child, principles formally recognized in the United Nations Convention on the Right of the Child (UNCRC). In addition to having moral and legal grounds to participate, children attribute a great deal of importance to being recognized and acknowledged as individuals with opinions and feelings of their own and as agents capable of contributing to decision making in their everyday lives (Jang et al., 2016).

From a practical standpoint, there are sound research, policy, and programming reasons for taking a child-informed approach to understanding well-being (Casas, 2011; Chaplin, 2009). Children’s views widen our conceptual understanding of children’s well-being and add to the foundation on which to construct survey measures and indicators for monitoring their well-being in social indicators research. Children’s views may be useful in refining or validating researchers’ models of well-being, as well as in enhancing the precision with which well-being is assessed (Bourke & Geldens, 2007). How well an intervention, service, program, or lesson plan is received or valued by children in a certain setting depends on the opinions of the children who are directly affected by the program (Marchant et al., 2012). It is therefore imperative for any conceptualization of children’s well-being in schools not to ignore the ways in which children “have unique perspectives on learning, teaching, and schooling” (Cook-Sather, 2006, p. 359).

A number of research projects around the world explore children’s understandings of their well-being, e.g. The Australian Child Wellbeing Project (n.d.) and The Children’s Worlds : International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (n.d.). In one of their recent studies in New Zealand, Bharara et al. (2019) asked children aged 11 to 13 (N = 361) to imagine that they had to explain the concept of well-being to someone who does not know about well-being. Children were asked to list the components of well-being as well as their perceptions of what constitutes and promotes well-being. Children reported on aspects not prevalent in the literature on child well-being, namely that they consider enjoyment / having fun, feeling safe, and being kind / helpful as central components of well-being, while a sense of satisfaction was a peripheral component (Bharara et al., 2019).

In their longitudinal study exploring the evolution of subjective well-being in children aged 9 to 16 in North-East Spain, González-Carrasco et al. (2019) classified answers provided by children into five categories: Interpersonal relationships, Health, Leisure activities, School and Personal aspects. With regard to interpersonal relationships, relationships with family and friends were cited as key to well-being, specifically receiving support from, and spending time with, family members. Children noted the importance of good health and considered specific unhealthy habits (being inactive and eating poorly) to lower their well-being, while “doing leisure activities and having fun helps them feel good” (González-Carrasco et al., 2019, p. 486). Some personal aspects identified as attributes of well-being were: being satisfied with yourself, having few problems, and having life goals (González-Carrasco et al., 2019). The participants’ experience of the school environment was a central component in their well-being, however conflicting discourses were evident regarding the effects of the burden of homework and exams: for some, being able to do homework and to write exams was synonymous with being happy at school and getting good grades, whereas for others it lead to too much stress (González-Carrasco et al., 2019).

Family and education appear to be central constructs related to well-being for children. Older children’s conceptions of child well-being and ill-being in Vietnam focused on their school environment, friends, and studies (Crivello et al., 2009). Well-being was equated with having a healthy and happy life as well as being loved by their parents and the people around them (Crivello et al., 2009). Family was the central source of well-being for children in a study in Peru, specifically the presence of parents, as well as their love and support. (Crivello et al., 2009).

In the Canadian context, the Life Story Board (LSB) has been used to explore how twenty-one children between 8 and 12 years of age understand their own well-being (Stewart-Tufescu et al., 2019). Developed by Robert Chase, the LSB uses a visual schema to organize a narrative through pictorial representations of a persons’ life situation, including events, family and personal relationships, and community views (Chase, Medina & Mignone, 2012). The main well-being themes that emerged from this study were: autonomy and inclusiveness; validation of children’s experiences and agency; and adult caregivers who use a child-centred approach (Stewart-Tufescu et al., 2019).

Finally, there are recognizable benefits to student well-being when school leaders understand the experiences of students in schools. Research on student voice and student participation (De Róiste et al., 2012; Fielding, 2001) strongly suggests that listening and responding to what students have to say about their experiences at school can lead to positive outcomes in terms of satisfaction with school, enhanced learning experiences, higher attainment levels, improved engagement, and better relationships. As De Róiste et al. (2012) state, “satisfaction with school can be considered as a construct that contributes to life satisfaction and is indicated by happiness, enjoyment of school, a sense of well-being at school, and quality of life among young people” (p. 90). Research conducted by Soutter et al. (2012) in Australian schools found that having resources, being independent, relating well with teachers, functioning effectively in assessment-related activities, and striving towards earning credits were reported by older young people (17 to 21-years-old) as the most salient aspects in schools for cultivating well-being. Viewed through the lens of students, well-being was characterized as a relationship between developing assets (having, being, relating) and engaging in actions (functioning, striving) as well as appraisals (thinking, feeling), particularly in terms of making independent decisions and thinking positively (Soutter et al., 2012).

We want to make two general observations from this small sample of the relevant literature. First, there are large variations among the characteristics that children and students identify when asked how they understand well-being. Second, life context affects what characteristics children bring into focus: if children are asked in a school context, school experiences play a more prominent role (Soutter et al., 2012) compared to when asked outside of school (González-Carrasco et al., 2019). This provides a rationale for a study like ours, undertaken within a school context and focusing specifically on student well-being.

In addition, our review of the literature found very few studies that take as their starting point children’s own testimonies about what well-being means to them and particularly what a school ecology that supports student well-being looks like (for some exceptions, see Fattore et al., 2007; Nic Gabhainn & Sixsmith, 2005). While there is now an expanding literature on educational interventions used to address student well-being (Furlong et al., 2014), overwhelmingly, existing studies have not given consideration to the perspectives of students on what it means to flourish for them. Also, while there is some literature that takes as a starting point the researchers’ understanding of the kind(s) of well-being that would be supportive of school ecologies (e.g., Eccles & Roeser, 2011; Munn, 2010), we were not able to come across research that asks students for their perspectives. Finally, we found no studies that drew on student testimonies about the role of well-being as an educational aim. Our study was designed to help fill these gaps.

A SET OF THEORETICAL ASSUMPTIONS

This study does not assume a specific theory of human well-being or, in particular student well-being. Such assumptions would be in conflict with the purpose of the study. However, we have made some general assumptions. We have drawn these assumptions from a range of theories about well-being and childhood (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 2005; Nussbaum, 2011), without necessarily committing to all aspects of said theories.

The research project itself is motivated by the assumption that students’ views of their own well-being and their understanding of well-being matter to them as both students and future adults. This assumption is grounded in the above-mentioned recognition of childhood as a life phase in its own right. If childhood — and this includes childhood in schools — is understood as a phase in its own right rather than only as a transition phase toward adulthood, then there is such a thing as a “child’s world” that only children have access to and that is lost once a child becomes an adult (Falkenberg & Krepski, 2020). Thus, researching students’ and children’s well-being requires children’s voices on their own well-being, since they are the best source of what the “child’s world” is like.

While the first assumption for this study responds to the question of why a study like the present one is important, the next set of assumptions are about human well-being in general. While this study is trying to help us understand student well-being, we needed to make some general assumptions about the concept of well-being in order to design the study. We made the following three general assumptions about human well-being, each of which is reflected in one of the three interview questions:

the quality of one’s experiences and one’s behavior are indicative of the quality of one’s flourishing life1;

the ecology surrounding one’s life plays an important part in one’s well-being (we use ecology in the broadest sense, to include the social, natural, and physical systems in which students are embedded); and

having capabilities plays an important part in being able to live a flourishing life.

We made one additional assumption that led us to the formulation of the third interview question: understanding students’ well-being needs to include the educative mandate of schooling as the ecological setting for being a student.

On the basis of these four assumptions we designed this study, the findings of which we are presenting in this article.

STUDY DESIGN

The study, which received approval from the research ethics board of our university, was undertaken during the school year 2017-18 at a large high school (grades 10-12) in Winnipeg, Canada. At the time of the study, about 1,300 students attended the school.

A Steering Committee for the study was established, which consisted of the university-based researchers, members from the school administration, and members from the school’s Mental Health Committee. The purpose of the Steering Committee was two-fold: to oversee the planning and implementing of the study, and to coordinate the utilization of the study findings.

PURPOSE

The purpose of the study was to contribute to the understanding of how students themselves conceptualize student well-being, what school ecology they consider conducive for student well-being, and the role of student well-being as an aim of school education. The focus of the study was, thus, on students’ understanding of what it means to flourish as a student in general rather than on their own well-being experiences as students at the particular school where the study took place.

The specific research questions that directed the study were: (1) What is the participating students’ understanding of the characteristics of a flourishing student? (2) What is the participating students’ understanding of the qualities of a school ecology that supports students’ well-being? and (3) What is the participating students’ understanding of the capabilities that schools should develop in students so that they flourish (a) as students and (b) as adults in the future?

PARTICIPANTS

In order to draw on a diverse group of students, the Steering Committee invited students attending different types of classes to participate in the study : students in a band class; students in a class for newcomers with very low English-language competency (these students responded to the survey through an interpreter); students on a sports team; students involved in a mental health club; and students enrolled in a general science course. Fifty students in total responded to the survey, which represents about 4 % of the total school population. Students who participated in the survey were also invited to participate in one of four focus group interviews. Twenty-four of the 50 students participated in the focus group interviews. Each of the focus groups involved four to six participants. Students from each of the classes participated in the focus group interviews, except students from the class for newcomers.

DATA AND DATA COLLECTION

Data were collected through an open-ended written survey and four focus group interviews that were audio-recorded and then transcribed. Survey data were collected first, then the focus group interviews were undertaken. The five survey questions and the four questions guiding the semi-structured focus-group interviews were designed to elicit responses from students that helped us answer each of the three research questions. While the survey questions were answered individually and without any opportunity to ask follow-up questions or prompts, the interviews provided such opportunities.

DATA ANALYSIS

We analysed the written survey responses and the transcribed interviews. For this analysis, we followed Maxwell’s (2013) generic design for qualitative data analysis in our use of what he calls “categorizing strategies” (p. 106), of which coding is the main type in qualitative research. We used open coding of participants’ responses to arrive at initial organizational categories of responses to each of the survey and interview questions (Maxwell, 2013). This first step allowed us to cluster all responses from the participants into a system of organizational categories for each of the survey and interview questions. Then we developed “substantive categories” (Maxwell, 2013, p. 108) within each organizational category by drawing on the content of each categorized response. Finally, we clustered the substantive categories into “theoretical categories” (Maxwell, 2013, p. 108), which are categories that allow us to respond to the research questions at a theoretical level. One example of a theoretical category was “supportive school environment.” To justify our move from the organizational categories to the theoretical categories, we decided: (a) to include in the findings from the open-ended survey only those substantive categories for which there were at least 5 participants (10 %) whose responses fell into that substantive category; and (b) to include in the findings from the group interviews only those substantive categories for which there were responses in at least two of the four group interviews that fell into that substantive category.

STUDY FINDINGS

The findings of the study reported in this section are presented for each research question using the theoretical categories under which we have clustered the content categories. For each of the three research questions, we present the findings for the survey and focus group interviews sequentially and then draw these findings together to offer an overall response to the respective research question.

In the presentation of the survey findings, the number provided after each theoretical sub-theme indicates the number of participants whose responses fit the respective sub-theme. Some responses might be listed under more than one subtheme within the same theme.

WHAT CHARACTERIZES STUDENT WELL-BEING

Survey

Table 1 provides an overview of the themes and their sub-themes derived from the participants’ survey responses.

TABLE 1. Thematic Survey Responses on What Characterizes a Flourishing Student

Themes |

Exemplifying Student Quotes |

Personal characteristics / attributes

|

“I really wish that everyone would realize that all are humans and they have feelings that can hurt, even with a single word. So I want everyone to be nice and kind to each other” “Happy, smiles, laughing, talking with friends” “Happy about being at school” |

Social functioning

|

“They will relate well and have lots of friends” “Have a feeling of belonging, knowing you’re not alone with your problems.” “Having lots of friends and people to talk to.” “Welcomed and accepted, people probably greet this person with a smile everywhere” “They get along well with others. They are probably popular” |

Relationship to learning and school more generally

|

“They enjoy it, and know they’re good at it” “Student enjoys school, takes part in activities and feels pride in putting his/her best work forward. In a right state of mind and is generally happy.” “School doesn't feel like a chore or something they dread. They have a healthy relationship with it because they look forward to weekend like everyone else but doesn't dread going to school or feel like they need to miss.” |

Supportive school environment

|

“He/she thinks school is a safe environment almost like a second home as the school is a community” “The student would feel safe and cared for and happy when they are at school.” |

Interviews

Table 2 provides an overview of the sub-themes that arose in at least two different focus group interviews and the major themes clustering sets of sub-themes. The next section integrates the findings from the interviews with those from the survey reported in Table 1.

TABLE 2. Thematic Interview Responses to the Main Interview Question of What Characterizes a Flourishing Student.

Personal characteristics / attributes

|

Physical appearance

|

Relational qualities

|

Friendship

|

Feelings about school

|

Curricular learning

|

Extracurricular activities

|

Students’ Views on Flourishing Students

Participating students’ views on what characterizes a flourishing student can be captured in the following categorical understandings.

A flourishing student is characterized by:

experiencing positive emotions (e.g., being happy, calm, comfortable, excited and motivated; feeling accomplished; feeling welcome);

having a positive disposition (e.g., being empathic, respectful, and helpful; being confident and feeling accomplished; being physically fit; living according to one’s values);

having positive social connections (e.g., being accepted by others / feeling welcome; being happy to be around others; having many friends; impacting the well-being of others; having good communication skills);

having a positive orientation toward schooling (e.g., enjoying school; working hard; being engaged);

being accomplished (e.g., doing well in school, being academically successful); and

being in a supportive school environment (e.g. being in a safe school; having extracurricular activities available; feeling welcome).

In addition to identifying categorical characteristics of what it means to flourish as a student, the findings also suggested that there are both “inner” and “outer” considerations to be taken into account. Firstly, a major feature of what it means to flourish as a student are the qualities of one’s being and one’s experiences: experiencing positive emotions; having positive dispositions; having a positive orientation toward school. Drawing on the quantitative information afforded by the survey, we can say that for the participating students these “inner qualities” (experiences, dispositions, and attitudes toward school) are most linked with their understanding of students’ well-being. However, secondly, the well-being of students is not just an “internal” matter, but is also characterized by the quality of the “outer” school ecology that allows students have certain experiences: a flourishing student feels safe, feels welcome, is accepted by others in the school, and has opportunities for extracurricular activities. It is important here to emphasize that the identified qualities of the school ecology have to be understood as an integral aspect of the conceptualization of what it means to flourish as a student: they are understood by the participants as necessary conditions for student well-being. Thirdly, as the interview data suggest, a flourishing student does not just have positive social connections, but has supportive skills or competencies that accompany the building and maintaining of such positive social connections: being friendly, being helpful, having good communication skills.

A SCHOOL ECOLOGY FOR STUDENTS’ WELL-BEING

Survey

TABLE 3. Thematic Survey Responses on What a School Ecology Looks Like that Supports Students’ Well-Being

Themes |

Exemplifying Student Quotes |

Well-being school ecology provides for extra-curricular activities

|

“I would have a free dance class for those who want to join.” “Lots of opportunity to play different sports” “Assembly / school gatherings about interesting topics and fun things could make student happier at the school” |

Well-being school ecology promotes conducive learning environments

|

“I would have many kinds of music classes, because its nice to step away from physics or chem for a while and just do music” “Offer extra credits to students who would need it” “Classes that are specialized to help students in the future with life skills such as cooking, cleaning, taxes and hands on skills like taking care of the school grounds and building or repairing. |

Well-being school ecology offers supportive relational surrounding: diversity and kindness, care and respect

|

“Have people who can help students and know how to deal with them and understand their background” “I would create a school with a nice, healthy environment, always surrounded by nice and kind-hearted teachers & students.” “I want the school to be a happy place where no one feels left out or sad. I do not want anyone to feel like they don't belong here.” |

Well-being school ecology provides a surrounding supportive of students’ mental health: safe school with opportunities to relax

|

“Meditation class: Meditation is good for us in many aspects of our body, it relaxes your mind and body and even affects your brain. So I think we should have meditation class once a week, so we can know how to meditate properly.” “First I would want to make sure that every student has a place where they come to feel safe and be with their friends. For me this is the band room because I know I can always find my friends there before school, at lunch and after school. |

Well-being school ecology offers choice to students

|

“Give a variety of different courses for their interest” “Wide choices of courses. Learning about something you find interesting helps a lot.” |

Well-being school ecology offers access to support resources

|

“Good guidance councillors who have experience in the past” “More support such as counsellors so that there is more of an opportunity to go and get individual help.” |

Interviews

Table 4 provides an overview of the sub-themes that arose in at least two different interviews and the major themes clustering sets of sub-themes. The next section integrates these findings from the interviews with those from the survey reported in Table 3.

TABLE 4. Thematic Interview Responses to the Main Interview Question of What Students Consider a School Ecology that Supports Students’ Well-Being to Look Like

Architecture and physical space as part of the well-being ecology

|

Well-being school ecology provides for extra-curricular activities

|

Well-being school ecology supports students’ future orientation: career and life

|

Well-being school ecology provides well-being curriculum / content: mental health, problem solving, social skills

|

Well-being school ecology promotes conducive learning environments

|

Well-being school ecology offers access to support resources

|

Students’ Views on School Ecologies that Support Students’ Well-being

The second research question — and the corresponding survey and interview questions — inquired into participating students’ views on features of a school’s ecology that would support students’ well-being. As we have seen, in response to the first research question, students suggested that certain qualities of a school’s ecology are conceptually implicated in their understanding of their well-being. The difference is that the responses to the second research question are empirical claims that students make about an environment that supports students’ well-being, while responses to the first research question involving school ecological qualities are part of how the students understand what it means to flourish as a student.

Students’ views on school ecologies that support students’ well-being can be clustered into four dimensions: physical surrounding; human surrounding; extra-curricular engagement; and curricular engagement. Students identified a number of characteristics of a well-being school ecology for each of the four dimensions, which are represented in Table 5.

TABLE 5. Characteristics of the Four Dimensions of School Well-Being Ecology

Dimensions of school ecology |

Characteristics of a well-being school ecology |

|

surroundings |

physical |

|

human |

|

|

engagement |

extra-curricular |

|

curricular |

Learning context

Curriculum

|

|

WELL-BEING CAPABILITIES TO BE DEVELOPED IN SCHOOL

Survey

Tables 6 and 7 provide an overview of the themes and their sub-themes and the number of participants who provided a response that fit the respective sub-theme. While capabilities are different from skills, participants often used the term “skills” in their responses to this survey question. The presented findings reflect students’ choice of terminology.

TABLE 6. Thematic Survey Responses on What Well-Being Capabilities Schools Should Help Students Develop to Flourish as Students

Themes |

Exemplifying Student Quotes |

Social skills

|

“How to relate to others” “Making friends” “Not being afraid of talking” “Treat others the way you would like others to treat you” “Respect and care about each other” “Empathy and being able to resolve conflict” |

Daily life skills (excluding social skills)

|

“Learning how to learn and organization of thoughts” “Daily lifestyle activities: punctuality, cooking and cleaning” |

Health capabilities

|

“Physical wellness and positivity” “Confidence - it is always important to be confident whatever you are doing” |

Other capabilities

|

“Learn knowledge about school subjects” “The ability to create and think of new ideas” |

TABLE 7. Thematic Survey Responses on What Well-Being Capabilities Schools Should Help Students Develop to Flourish as Adults

Themes |

Exemplifying Student Quotes |

Social skills

|

“Good social skills. Doing well in a career or relationship is nearly impossible when you’re unaware of how to talk to people” “Communication skills, it is important to communicate well in society” “Being fluent in English“ |

Daily life skills (excluding social skills)

|

“Be a responsible person” “Money management” “Real-world applications knowing how to cook, clean, do taxes, is very important in adult life.” |

Career-related capabilities

|

“They would get a good job for their skills” “Obtaining a degree and obtaining a job” “Being able to support yourself and get a job” |

Health capabilities

|

“Managing and maintaining good mental health” |

Other capabilities

|

“Explain, teach, talk about life after high school” “Decision making” |

Interviews

The following is a list of students’ responses to the thematic interviews on the question of what capabilities schools help student develop to flourish as both students and adults. In the interviews, students did not differentiate between capabilities needed only as students, and capabilities only as adults.

Capabilities:

to communicate well with others;

to relate to, engage well, and work well with other people (people skills);

to work intelligently with one’s emotions;

to be self-directed;

to manage one’s time; and

to self-improve.

Students’ Views on Well-being Capabilities for Schools to Develop in Students

The survey findings suggest that the capabilities that schools should help students develop to flourish as students fall overwhelmingly into the category of daily life skills. Among those, the most prominent are social skills. This finding also holds true for the capabilities that students said should be developed in schools to help students flourish as adults. Indeed, with one exception, students did not distinguish between capabilities schools should develop in students for them to flourish as students, and those schools should develop in students for them to flourish as adults. The one exception is the development of career-related capabilities, which of course are not relevant for students to flourish as students. However, students gave far more weight to daily life skills development than to career-related capabilities. The interview findings complemented some aspects of the survey findings in terms of specific capabilities, but they did not add anything substantial to the survey findings.

DISCUSSION

Our study aimed to understand how students themselves understand “student well-being”, what a school ecology that is supportive of student well-being looks like, and what capabilities schools should develop to support the well-being of students as students as well as future adults. In this section we discuss what our findings mean in light of already existing research.

CONCEPTUALIZING STUDENT WELL-BEING

Figure 1 summarizes the experiences and qualities that the high school students who participated in the study identified as characteristics of flourishing, i.e. their understanding of what student well-being means to them.

Positive School Environment

FIGURE

1. Conceptualizing

student well-being

The general characteristics of student well-being in Figure 1 concur with findings in previous studies on how children or students understand well-being. Positive emotions in Figure 1, enjoying life, and being happy are identified in Bharara et al.’s (2019) study; positive dispositions in Figure 1, and being kind / helpful are also identified in Bharara et al.’s (2019) study; positive social connections in Figure 1 and interpersonal relationships are identified in González-Carrasco et al.’s (2019) study; positive orientations toward school in Figure 1, being happy at school, and getting good grades are also identified in González-Carrasco et al.’s (2019) study. While general characteristics of child / student well-being vary across studies, there is clear overlap among characteristics. While each characteristic presented in Figure 1 is not new in research literature, as a whole, Figure 1 combined with the details presented in the findings section of this paper provide a unique set of characteristics. This set reflects a contextual-specific understanding of what student well-being means to these students. It complements the contextual-specific findings in other studies.

Our study supports Bharara et al.’s (2019) important finding that children’s understanding of well-being includes characteristics that generally cannot be found in researcher-based models of child well-being, like being kind / helpful (“being empathic / respectful” in our study), feeling safe (“being in a safe school” in our study), and being happy (“being cheerful”; “being happy in and enjoying school” in our study). These observations strengthen the case for the first theoretical assumption that we have made, namely that children’s / students’ perspectives on well-being matter for different, important reasons, one of which is that they are the best informant on what it is like to be a child /student.

SCHOOL ECOLOGY FOR STUDENTS’ WELL-BEING

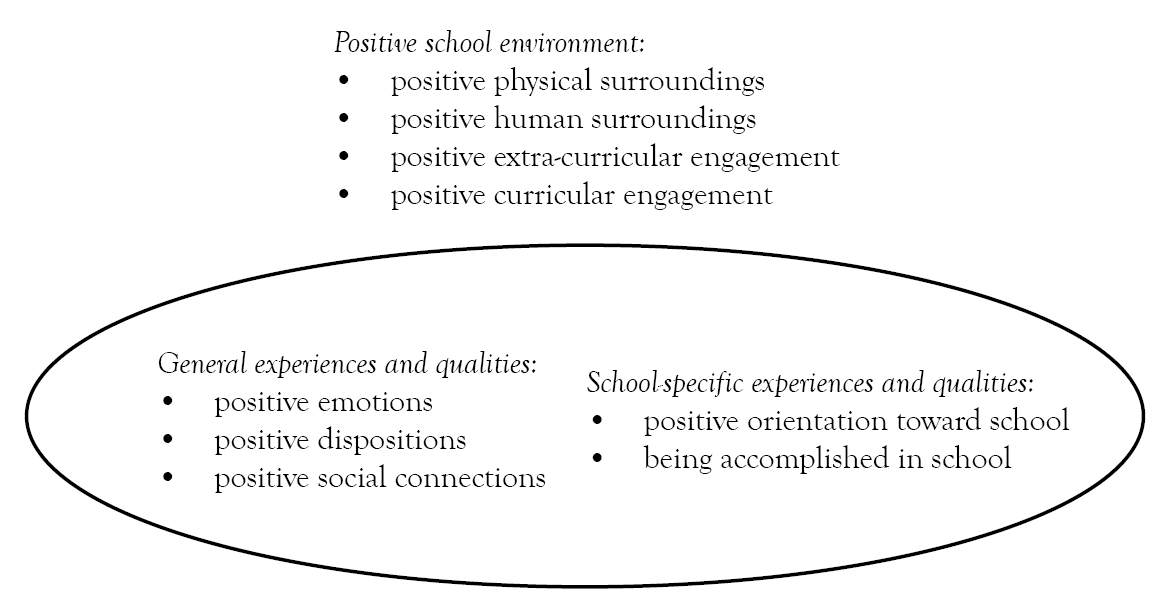

Based on students’ responses, Figure 1 can be expanded into Figure 2 to include those categorical characteristics that participants identified as central to a positive school environment that supports student well-being. Table 5 shows students’ rich understanding of diverse ecological features that support student well-being.

FIGURE

2. Conceptualizing

student well-being within a supportive school ecology

As introduced above, the UNCRC articulates expectations of those holding power over and responsible for children to provide a developmental ecology that is supportive of children’s well-being, while also expanding earlier child rights declarations to include participation rights. Students’ collective understanding of the qualities of a school ecology that supports student well-being (see: Table 5) suggests a similarly expansive understanding. On one hand, there is an understanding of a well-being-supportive school ecology that is concerned with safe schools and supportive educators. On the other, we find the understanding that supportive school ecologies provide students with choices. Our study contributes uniquely to this focus on student perceptions of school ecology and its impact on well-being.

CAPABILITIES DEVELOPMENT FOR WELL-BEING

One of our theoretical starting points was the assumption that having capabilities matters to one’s well-being. The richness and extensiveness with which students responded to survey and interview questions on the role of (certain) capabilities in school education demonstrated that and how these capabilities indeed matter to their well-being. Thus, our study complements research that supports the view that a capabilities approach to well-being is relevant to the understanding of children’s views on what it means for them to flourish (Biggeri et al., 2006). It also complements the literature that theorizes about the important contributions that the capabilities approach to human well-being can make as a theoretical framework for school educational policy, practice, and purpose (e.g., Robeyns, 2006).

As far as the role that schools have in developing relevant capabilities is concerned, students have specific ideas about what that should be, on which we make two observations. One is that the dominant group of such capabilities are daily life skills, particularly social skills. We claim that this is in opposition to what — at least in Canada — high school education generally focuses on in terms of curricular priorities and resource allocation, instead tending to focus on the dominant academic disciplines / subject areas. The second observation is that, with one exception, the types of capabilities that students identify as those to be developed for students’ current well-being are identical with those to be developed for students’ future well-being as adults; the one exception is carrier-related capabilities. This suggests that for students, school aims are both future and present-oriented. Moreover, what is generally relevant for the future is also relevant for the present and vice versa. This is important to note, given that students cannot draw on direct experience of what it means to live a flourishing life as an adult and that they might have a vague notion of how their life might change as an adult.

LIMITATIONS

The design of the study limits generalization and transferability of the findings. First, the survey used language that some of the student participants might not be sufficiently familiar with, so some of the respondents might have responded to a different question than the one we intended to pose. However, while not all survey participants took part in the focus-group interviews, interviewers tried to make sure that participants understood the questions in the intended way. Second, limitations from the recruitment process are linked to the relatively small sample size (N = 50 for the survey; N = 24 for the interviews), and also to the facts that no demographical data were collected from participants, with only students from one particular school participating. However, the recruitment process tried to reflect the diversity of the school’s student population by recruiting students that attended quite different courses, including one course specifically created for newcomer students.

CONCLUSION

The well-being of students has become of greater explicit concern to school education in Canada and beyond. In order for this concern to translate into educational policy, practice, and purpose, we need to develop an understanding of what it means for students to flourish (i.e., student well-being). The study presented in this paper contributes to an underexplored approach by inquiring into high school students’ perspectives on what it means to flourish as a student, what a school ecology supportive of student well-being looks like, and what well-being capabilities schools should focus on as educational aims.

In our introduction, we suggested that in one respect our study continues the tradition of research inquiring into students’ perspectives on school matters affecting them (Wilson & Corbett, 2001). Our study is specifically focused on student well-being. However, findings from research into students’ perspectives on school matters align very well with findings in our study. For instance, our findings on students’ views on the characteristics of a school ecology that is supportive of well-being align well with findings in studies of students’ views on how schools can be improved (Rudduck, 2007). We see our study as “bridging” the two research literatures, thus encouraging continued research within and across fields.

We would like to give the last word in this paper to one of our student interviewees:

I think, like wellbeing is like how you feel about yourself and like, if your confident about what you’re doing, and you’re, like let’s say you find what you’re good at and you’re doing well in that, it makes you feel better about yourself than, I don’t know, trying to do let’s say you know someone who is really good at math but you’re good at science, and you suck at math, like you can’t feel bad about yourself, like if you could just flourish in the courses that you’re good at, like it would make you feel better about yourself, just being like comfortable, with like where you are at school and liking life is like, a big part of being mentally healthy. (B &Y Interview)

NOTES

We are using the term flourish (and its derived forms) whenever we need to use a verb (she flourishes) or adjective form (a flourishing life) to draw on the meaning of the noun “well-being”, since she is well and a well-being life would not capture the intended meanings.

Acknowledgements

We like to thank the students who participated in the study, the school’s administration, and the members of the Mental Health Committee and the study’s Steering Committee. Without their support, the study would not have happened. We also would like to acknowledge financial support for this study by the Faculty of Education of the University of Manitoba.

REFERENCES

Alberta Education (2009). Framework for kindergarten to grade 12 wellness education. https://education.alberta.ca/wellness-education/wellness-education/

The Australian Child Wellbeing Project. (n.d.). www.australianchildwellbeing.com.au

Bagattini, A. & Macleod, C., (2015). The nature of children’s well-being. Springer.

Ben-Arieh, A. (2008). The child indicators movement: Past, present, and future. Child Indicators Research, 1, 3-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12187-007-9003-1

Bharara, G., Duncan, S., Jarden, A., & Hinckson, E. (2019). A prototype analysis of New Zealand adolescents’ conceptualizations of wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 9(4), 1-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v9i4.975

Biggeri, M., Libanora, R., Mariani, S., & Menchini, L. (2006). Children conceptualizing their capabilities: Results of a survey conducted during the First Children’s World Congress on Child Labour. Journal of Human Development, 7(1), 59 – 83. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880500501179

Bourke, L., & Geldens, P. M. (2007). Subjective wellbeing and its meaning for young people in a rural Australian center. Social Indicators Research, 82, 165–187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9031-0

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (Ed.).(2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Sage Publications.

Casas, F. (2011). Subjective social indicators and child and adolescent well-being. Child Indicators Research, 4(4), 555–575. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12187-010-9093-z

Chaplin, L. N. (2009). Please may I have a bike? Better yet, may I have a hug? An examination of children’s and adolescents’ happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(5), 541–562. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9108-3

Chase, R., Medina, M. F., & Mignone, J. (2012). The life story board: A feasibility study of a visual interview tool for school counsellors. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 46(3), 183–200.

The Children’s Worlds: International Survey of Children’s Well-Being. (n.d.). www.isciweb.org

Cook-Sather, A. (2006). Sound, presence, and power: “Student voice” in educational research and reform. Curriculum Inquiry, 36(4), 359–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-873X.2006.00363.x

Cook-Sather, A. (2009). Learning from the student's perspective: A sourcebook for effective teaching. Paradigm Publishers.

Crisp, R. (2013). Well-being. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (Winter 2021 ed,) Standford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2016/entries/well-being/

Crivello, G., Camfield, L., & Woodhead, M. (2009). How can children tell us about their wellbeing? Exploring the potential of participatory research approaches within young lives. Social Indicators Research, 90, 51–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9312-x

De Róiste, A., Kelly, C., Molcho, M., Gavin, A., & Gabhainn, S. N. (2012). Is school participation good for children? Associations with health and wellbeing. Health Education, 112(2), 88–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/09654281211203394

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225-241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00725.x

Falkenberg, T. (2014). Making sense of Western approaches to well-being for an educational context. In F. Deer, T. Falkenberg, B. McMillan, & L. Sims (Eds.), Sustainable well-being: Concepts, issues, and educational practices (pp. 77-94). Winnipeg, MB: ESWB Press. www.ESWB-Press.org

Falkenberg, T., & Krepski, H. (2020). On conceptualizing child well-being: Drawing on disciplinary understandings of childhood. Canadian Journal of Education, 43(4), 891–917.

Fattore, T., Mason, J., & Watson, E. (2007). Children’s conceptualisation(s) of their well-being. Social Indicators Research, 80(1), 5–29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-006-9019-9.

Fielding, M. (2001). Beyond the rhetoric of student voice: New departures or new constraints in the transforming of the 21st century schooling? Forum, 43(2), 100–110. https://doi.org/10.2304/forum.2001.43.2.1

Furlong, M. J., Gilman, R., & Huebner, E. S. (Eds.). (2014). Handbook of positive psychology in schools (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Gheaus, A. (2015). The ‘intrinsic goods of childhood’ and the just society. In Bagattini, A. & Macleod, C. (Eds.), The nature of children’s well-being (pp. 35-52). Springer.

Gheaus, A. (2018). Introduction: Symposium on the nature and value of childhood. Journal of Applied Philosophy. 35(S1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12280

González-Carrasco, M., Vaqué, C., Malo, S., Crous, G., Casas, F., & Figuer, C. (2019). A qualitative longitudinal study on the well-being of children and adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 12(2), 479–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9534-7

James, A., Jenks, C., & Prout, A. (1998). Theorizing childhood. Teachers College Press.

Jang, H., Reeve, J., & Halusic, M. (2016). A new autonomy-supportive way of teaching that increases conceptual learning: Teaching in students’ preferred ways. The Journal of Experimental Education, 84(4), 686–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2015.1083522

Lundy, L. (2014). United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and child well-being. In A. Ben-Arieh, R. Casas, I Frønes, & J. E. Korbin (Eds.), Handbook of child well-being: Theories, methods and policies in global perspective (pp. 2439-2462). Springer.

Marchant, M., Heath, M. A., & Miramontes, N. Y. (2012). Merging empiricism and humanism: Role of social validity in the school-wide positive behavior support model. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 15(4), 221–230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1098300712459356

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Munn, P. (2010). How schools can contribute to pupils’ well-being. In C. McAuley & W. Rose (Eds.), Child well-being: Understanding children’s lives (pp. 91-110). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Nic Gabhainn, S. N., & Sixsmith, J. (2005). Children’s understanding of well-being. The National Children’s Office.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. Harvard University Press.

Ontario Ministry of Education (2014). Achieving excellence: A renewed vision for education in Ontario. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/about/excellent.html

Robeyns, I. (2006). Three models of education: Rights, capabilities and human capital. Theory and Research in Education, 4(1), 69-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878506060683

Rudduck, J. (2007). Student voice, student engagement, and school reform. In D. Thiessen & A. Cook-Sather (Eds.), International handbook of student experience in elementary and secondary school (pp. 587-610). Springer.

Rudduck, J., & Demetriou, H. (2003). Student perspectives and teacher practices: The transformative potential. McGill Journal of Education, 38(2), 274–288.

Smyth, J. (2007). Toward the pedagogically engaged school: Listening to student voice as a positive response to Disengagement and ‘dropping out’? In D. Thiessen & A. Cook-Sather (Eds.), International handbook of student experience in elementary and secondary school (pp. 635-658). Springer.

Soutter, A. K., O’Steen, B., & Gilmore, A. (2012). Students’ and teachers’ perspectives on wellbeing in a senior secondary environment. Journal of Student Wellbeing, 5(2), 34–67. https://www.ojs.unisa.edu.au/index.php/JSW/article/download/738/582

Stewart-Tufescu, A., Huynh, E., Chase, R., & Mignone, J. (2019). The Life Story Board: A task-oriented research tool to explore children’s perspectives of well-being. Child Indicators Research, 12(2), 525–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9533-8

Tomlin, P. (2018). Saplings or caterpillars? Trying to understand children’s well-being. Journal of Applied Philosophy. 35(S1), 29-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12204

Wilson, B. L., & Corbett, D. (2001). Listening to urban kids: School reform and the teachers they want. State University of New York Press.