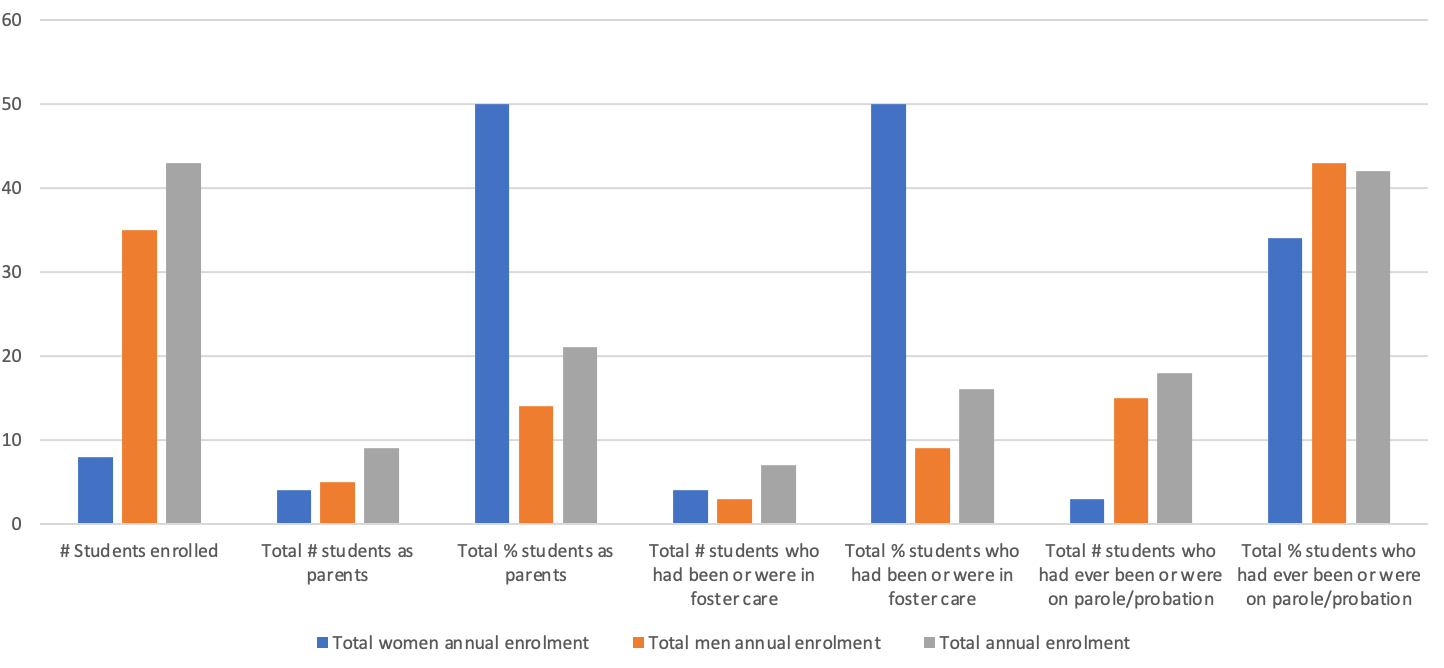

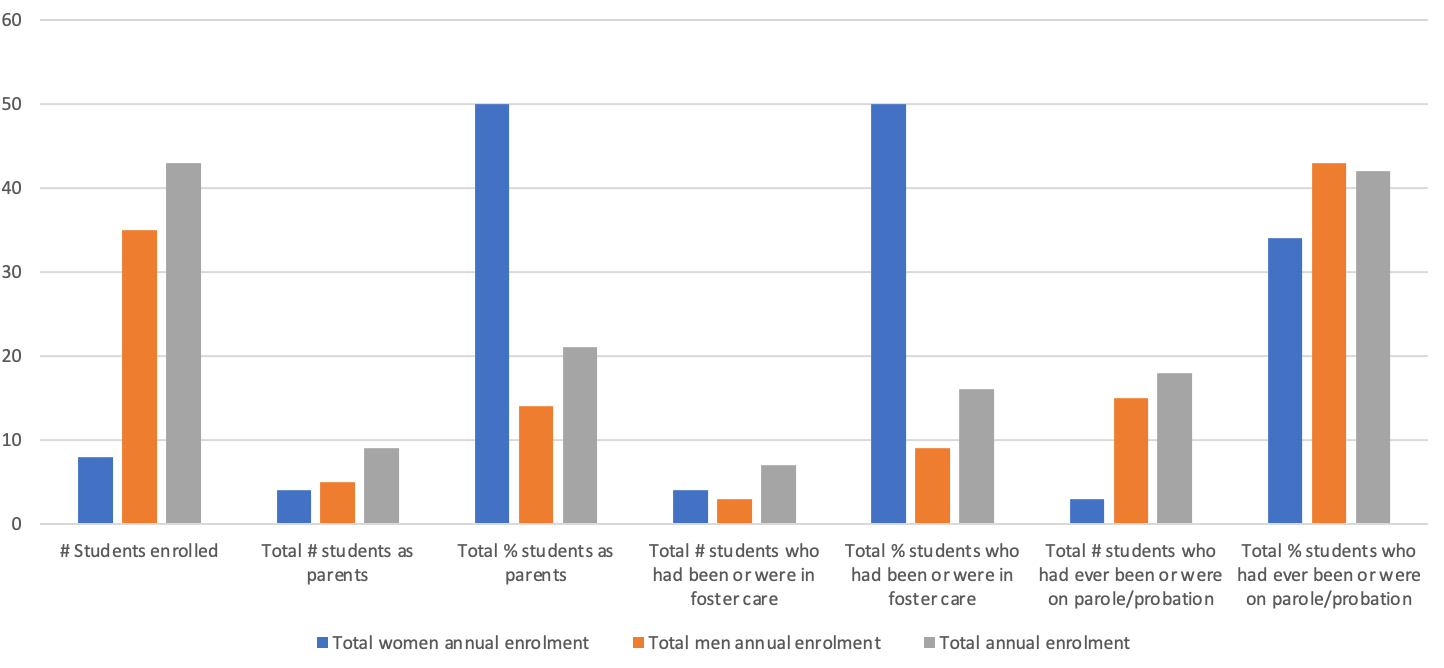

FIGURE 1. Demographic enrolment data for HSRA LA for academic year 2018–19

How to pay your students to go to school: Student-run record labels and the creative pedagogue

MICHAEL LIPSET McGill University

During the 2018–19 academic year, I served as the acting executive director at the High School for Recording Arts Los Angeles (HSRA LA) pilot program, a credit-granting high school program founded by the same educators who started the first High School for Recording Arts in St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1998. High School for Recording Arts (HSRA) was started by Twin Cities rap artist David “TC” Ellis out of his downtown recording studio as a response to young people in his community seeking a culturally sustaining educational alternative (Seidel, 2011). As a result of its origins in Hip-Hop culture, the school has been affectionately dubbed “Hip-Hop High.” The school’s mission is to serve opportunity youth ¾ young people between the ages of 16 and 24 who are out of work and school (Belfield et al., 2012, p. 5). Public charter schools began in the US in response to the inflexibility of the non-charter public sector. They allow qualified applicant schools to operate with certain derogations and autonomies otherwise not afforded to traditional public schools to foster growth, development, and innovation not achieved in the public sector (Nathan, 1996).

During the 2018–19 school year, my co-founders, founding team, and I partnered with the YouthBuild Charter School of California (YCSC) to operate this credit-granting high school program. We were lucky to find a partner in YCSC who allowed us to identify our own staff and run our own program in Downtown Los Angeles. YCSC holds a special designation as a public charter school allowed to operate multiple sites across California. Each site operates in partnership with a workforce and vocational training organization. We provided the vocational training to YouthBuild’s high school certification, which allowed HSRA LA to bring our expertise in the recording arts to LA’s opportunity youth. Through this partnership, we were able to provide a workforce and vocational training program with a full-stack high school diploma.

We also partnered with the American Jobs Corps. Through a piece of federal legislation called the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), the Jobs Corps enabled us to hire our students as interns and pay them to run their own record label. The WIOA fund distributes federal funds to organizations at the municipal level. These organizations, identified by the state, are responsible for identifying providers of youth internship opportunities in professional fields. We offered our students vocational training in the recording arts by providing them with the infrastructure and competencies to run their own record label. This paper examines the mechanisms in place to pay young people to go to school and run their own record label, and the effects of this student-run enterprise on student engagement and those operating the school, which produced a turn towards what could be called the role of a “creative pedagogue.”

Furthermore, this paper contributes to the literature on opportunity youth (Belfield et al., 2012) and the WIOA program (United States Department of Labor, 2019). Opportunity youth are the target audience of the WIOA program and, though this population has received plenty of research on its defining characteristics and required wraparound services, less research has been done on the practical applications of the WIOA program in support of deeper learning in the creative industries (Belfield et al., 2012; Hossain, 2015; Moore, 2016). Under President Obama, the WIOA recognized the important roles of education and work in the lives of those young people on the receiving end of some of America’s most oppressive systems (Hossain, 2015). As a result, the WIOA purposefully makes provisions for opportunity youth to attend school and receive credit for paid vocational training. As our program unfolded its unique student-run record label internship program, I began complicating my approach to school leadership towards the role of a creative pedagogue.

The definition of a creative pedagogue was formed because of the work covered in this paper. In reflecting upon the work of teaching artists, this term stems from definitions of a teaching artist but with a particular emphasis on 21st-century skills and competencies that include elements of a school curriculum as well as innovative, non-traditional, artistic paths to teaching and learning. The concept of a creative pedagogue most directly stems from that of the teaching artist who, according to Eric Booth (2009), “[i]s an artist who chooses to include artfully educating others, beyond teaching the technique of the art form, as an active part of a career” (p. 3, Chapter 1). Booth also identifies teaching artists as virtuosic artists unto themselves (p. 7, Chapter 1). Adding to this understanding of what constitutes a creative pedagogue, Booth names collaboration with classroom teachers as supportive of the goals of teaching artists broadly (p. 9, Chapter 1). Considering the notion that Hip-Hop–based educators bring a social justice lens with them into educational contexts (Akom, 2009), and as Baldwin (1962) says, that “the precise role of the artist … is to make the world a more human dwelling place,” the creative pedagogue is also someone who engages in their practice in order to disrupt and dismantle systemic forms of violence such as racism, sexism, classism, ableism, and the like (p. 1).

Given the increase in demand from today’s young people for stable jobs in the creative industries (Campbell, 2020), a creative pedagogue must also be explicitly dedicated to cultivating competencies relevant to careers as creative professionals. Based on these characteristics of a creative pedagogue, classroom teachers, teaching artists, and community members can all be considered creative pedagogues depending on their ability to educate young people through art-based, social justice–oriented, collaborative learning opportunities that develop professional skills in creative industries. The characteristics of creative pedagogues just described position them in distinct opposition to neoliberal aspects of today’s society that emphasize laissez-faire economic policies, individual competition over collaboration, and the perpetuation of systems that concentrate wealth in the hands of the few (Cairns, 2013; Orlowski, 2011).

Context

The re-engagement of opportunity youth into high school, i.e., the work of the High School for Recording Arts, differs from traditional education for a number of reasons. First, opportunity youth are often low-income and racialized (Belfield et al., 2012, p. 8). Opportunity youth are also subjected to houselessness at increased rates, have children at younger ages, and often have to earn money to contribute to their households (Belfield et al., 2012). Schools serving opportunity youth often develop wraparound service offerings in response to student needs that include support with housing, childcare, food, clothes, toiletries, securing official documents (e.g., identification cards and birth certificates), mental health services, and paid work (Moore, 2016). YCSC and HSRA both have a defined mission to serve this population, and each is well-versed in the needs of opportunity youth. Having found that our young people tend to skip school in favour of money-earning opportunities, the possibility of paying them for vocational training during school hours through the WIOA program seemed invaluable. Though this paper covers a US-based school, information that shows potential for such programs in Canada is provided in the Discussion section.

Research shows that experience is the best form of certification one can attain in a creative industry like the recording arts, and that increasingly, young people seek careers in creative industries (Campbell, 2013). Even so, the creative industries lack the same kinds of scaffolding and institutional recognition provided to other, more standardized vocational training paths like those of a pipefitter, electrician, or ironworker (Campbell, 2020). Knowing the precarity of work in creative industries like the recording arts, we considered the skills of teamwork and collaboration as crucial for our young people to begin imagining themselves as professionals working together, rather than as lone actors seeking success. Instead of uplifting the traditional notion of artists as solitary creatives (Baldwin, 1962), we connected artistry to teamwork by defining roles and building goals collectively to combat damaging notions of competitive individualism espoused by America’s approach to the acquisition of wealth (Orlowski, 2011).

Two goals of the internship program included increasing attendance / enrolment in the school and providing young people with real-world paid internships in the recording industry. Fundamentally, the HSRA LA team aimed to develop students’ sense of responsibility to community and to forego the competitive individualism that both traps (by isolating) and defeats agency, and we encouraged purpose in social justice and artistic initiatives. To do so, we felt the need to instruct students in how to navigate existing “systems” while also working to subvert them. As a result, we had to conscientiously toe the line between developing enough competence in survival skills while preserving enough sense of agency and community to work for change. These skills included fostering forms of cultural capital germane to students’ lived experiences that Tara Yosso (2005) identifies as “aspirational, navigational, social, linguistic, familial, and resistant” to combat racism, sexism, misogyny, classism, homophobia, transphobia, islamophobia, xenophobia, linguicism, and more (p. 69). By doing so, we were able to identify skills and competencies to strengthen within our students, as opposed to adhering to conceptions of business skills that did not align with our students’ lived experiences. In this way, our approach to the student-run record label fell within what Ginwright et al. (2007) refer to as a “critical civics praxis” that acknowledges structural constraints in young people’s lives, but also views young people “as active participants in changing debilitative neighbourhood conditions” (p. 694).

Attendance at a public school like ours may be viewed as within the paradigm of a neoliberal system of public education designed to produce the next generation of wage labourers (Parsons, 1964; Tyack & Cuban, 1995). HSRA, designed with the express purpose of serving out-of-school youth, uses a personal learning plan for each student, allows students to design their own project-based learning opportunities, and, through these student-centred approaches to education, empowers students to take ownership of their learning experiences, thus breaking down the aforementioned paradigm in the process (Seidel, 2011). At HSRA LA, we also dedicated our school community to zero suspensions or expulsions and committed to transformative justice as a form of conflict resolution that excluded the police and criminal (in)justice system from our school at all costs. In these ways, our community valued the active resistance of neoliberal mechanisms of schooling that have led to the hyper-disciplining of Black and Brown students, the school-to-prison pipeline, the adultification of young Black women, and the ghettoization of schools serving predominantly Black, Brown, and Indigenous students (Anyon, 1997; Darling-Hammond, 2000; Love, 2019; Morris, 2016).

Methods: Secondary data analysis

The research in this paper draws on secondary data on attendance, enrolment, the number of students officially hired into the internship program, and ethnography. I have limited the use of my ethnographic journal to excerpts that do not make students or staff identifiable. Because the data are anonymous, publicly available, and cannot be linked to the individuals who provided them, research ethics board review was not required. From this data set, I draw preliminary findings on potential impacts of the student-run record label on the school’s ability to serve students. Taken together, the findings support programs that pay young people to attend school, provide more opportunities for paid work in school, and pair paid professional experience in the creative industries with for-credit education. I also examine the turn from school leader into the role of a creative pedagogue.

Connecting Hip-Hop Based Education, Opportunity Youth, and WIOA

I position this paper within the literature on arts in education since the findings contribute to ongoing advocacy for the arts as essential to a well-rounded education (Booth, 2009; Gardner, n.d.; Gee, 2004; Seidel, 2013). Research in the US shows that, of all mentions of the arts in schools in the media, roughly half position the arts as subject to removal due to budget cuts or as working in opposition to improving standardized test scores (Gould, 2005; Tamer, 2009). Often, the arts only receive support in schools when the medium of artistry falls within classical artforms such as ballet, theatre, orchestral music, painting and sculpture (Gaztambide-Fernández, 2013). The student-run record label highlighted here, however, falls within the bounds of Hip-Hop–Based Education (HHBE), a field that covers the broad interactions between Hip-Hop culture and education (Petchauer, 2009). To date, HSRA has been identified as one of very few high schools in the US to centralize Hip-Hop culture as the overarching school culture (Seidel, 2011). In so doing, HSRA makes Hip-Hop, a culture regularly identified and stigmatized for its proximity to Black culture, into an asset, a symbol of inclusion, and a reminder of the need to maintain a focus on social justice in education (Seidel, 2011). Due to the stigmas surrounding Hip-Hop culture and the necessity for HHBE to be rooted in social justice (Akom, 2009; Alim & Paris, 2017; Emdin & Lee, 2013; Hill & Petchauer, 2013; Ibrahim, 2004; Ladson-Billings, 2017; Love, 2015; Rodriguez, 2009; Wong & Pena, 2017), this paper also incorporates the ways high schools can incorporate student-run record labels via HHBE for the re-engagement of out-of-school youth in social justice-oriented ways.

Mobilizing the WIOA program for opportunity youth

Our small program enrolled nine students before the start of the first year. We held three full-time staff positions that included me; a full-time, certified teacher; and a studio production and recording facilitator. The number of actively enrolled students grew over the course of the year and peaked during Trimester 3. Every student enrolled in our program over the year fit the category of opportunity youth. Only one of our students considered herself White, while the rest identified as Black or Latinx. Of the 43 total students in our program, 18 had been court-involved upon enrolment. Of the young women, 50% were mothers under the age of 24. Total enrolment by the end of each trimester grew from 21 active students at the end of Trimester 1 to 28 by the end of Trimester 3. Figure 1 displays demographic data of total annual enrolment and shows the level of need among our student population.

It took the majority of the year for us to discover how to make the internship program possible for our students. As a result, we could not set a start date for the program until the first day of Trimester 3. This delay meant that we did not inform our students of the opportunity until shortly before the beginning of Trimester 3, which left little time to prepare, hire students, and begin the internship before the year was over. More detail covering the importance of these challenges can be found in the Findings section.

Through the WIOA, certain schools qualify to receive WIOA status, which YCSC did. Research was done on the legislation to find out more about the WIOA program, which showed that it was designed to increase the chances for opportunity youth to win gainful employment and earn a high school diploma. Given our mission of serving opportunity youth in Los Angeles, a location we chose both for the devastating number of opportunity youth in the city and for its proximity to a robust recording arts industry, the combination of vocational training in the recording arts and the education needs of LA aligned well with each other. The WIOA legislation allowed our school to enrol and serve youth up to the age of 24 (Hossain, 2015), something traditional schools in California are not allowed to do (Escudero, 2019). WIOA legislation also made it possible for opportunity youth to be paid for vocational training and gain school credit for those experiences (United States Department of Labor: Employment and Training Administration, 2019). Our partnership with YCSC, designated as having WIOA status, made this internship program possible.

FIGURE 1.

Demographic

enrolment data for HSRA LA for academic year 2018–19

FIGURE NOTES. Figure 1 represents demographic data indicative of some of the challenges faced by our student population. Data on gender non-conforming students were not publicly available.

As the definition of a creative pedagogue requires community involvement and partnerships, how we established our WIOA program matters to the ways in which we turned from education professionals to creative pedagogues throughout the experience of building this program. In LA, one organization receives all federal funds for the city’s WIOA program. That organization provides funds to WorkSource centres around the state, which then distribute them to local programs. We connected our school with a local WorkSource centre, a division of America’s Jobs Corps, which then designated our school as a work site. The WorkSource centre acted as our accounting department, processing our interns’ timesheets and application paperwork and distributing the interns’ paychecks. It made 22 positions available to our site, pending submission of required documentation for each intern. At the beginning of Trimester 3, we had 24 students actively enrolled in our school, three of whom were independent study students and thus ineligible for the program. The remaining 21 students were eligible. Each intern would get paid minimum wage in LA ($13.25 USD per hour) for a maximum of 100 hours on campus. Interns were offered an additional 20 hours by our WorkSource centre partner to attend programming on how to manage their finances. The state of California, the federal government, the Jobs Corps, and clients of our student-run record label all became partners to the school in our efforts to provide this unique learning opportunity to our students, thus fulfilling the community partnerships component within the role of a creative pedagogue.

The marriage of work and schooling serves to reinforce neoliberal notions of education as a vehicle for professional attainment (Anyon, 1997; Cairns, 2013; Orlowski, 2011). Therefore, building this program could have undermined our efforts to educate students through a social justice lens as creative pedagogues. Public schools have time and time again been accused of funneling Black, Brown, and Indigenous students from working class backgrounds into working class jobs while reserving the most valuable opportunities for those who come from middle / upper-class backgrounds, who are usually White (Lipman, 2004). By engaging in the WIOA program at our site, we risked replicating this damaging cycle. However, as a school rooted in personalized, project-based learning through the recording arts and the only such school to do so in LA at the time of this program, we offered our young people a unique and rare opportunity. By focusing the mechanisms of the student-run record label on a team-based operational structure wherein success could only be found through cooperation between students and staff, we actively worked to combat neoliberal notions of schooling that value individual achievement over collective striving, grades over personal well-being, and pre-determined curricula over student interests. As well, by virtue of offering this opportunity to students whom the education system had largely forgotten, the program worked to combat students’ experiences with schooling that had offered them only the most remedial forms of education. In our view, the skills they were learning could be applied to the recording arts and many other aspects of their lives. Our commitment to social justice as a school meant we engaged in the work of social justice as a through line to our work, establishing social justice as a pillar of our work as creative pedagogues.

The internship experience

This section describes the internship experience and discusses its relevance to the component parts of the work of a creative pedagogue. Our staff and students collectively identified five main goals for the internship:

1) to provide learning in core content areas,

2) to promote the music they had made over the course of the year,

3) to learn the practical skills of running a record label,

4) to meet the basic expectations of most professional jobs, like timeliness and product outcomes,

5) and to promote the school to the community and engage the community in the school.

To establish high expectations for our interns, we interviewed each student for four kinds of internship positions. These four positions are in Table 1.

TABLE 1. The four available internship positions

Media database management intern - Mine and gather contacts for radio and news media; enter contacts into management system - Develop list of influencers and individuals who could help promote interns’ work |

Media promotions intern - Design artwork, flyers, social media messages, and album covers for promotion of various creative products - Manage social media accounts, develop relevant hashtags, make a post schedule, target influencers, document daily work of record label |

Student publicist intern - Draft press releases and outreach emails; work with team to finalize and distribute to contacts gathered by the media database management intern |

Music producer / Beatmaker intern - Make music for radio ads, videos, songs, social media posts, and customers

|

During interviews, we asked our students several questions to determine their primary area of interest for the internship. To break down the notion that careers consist of only one area of expertise or practice, we made it clear that on such a small team they would be gaining experience in each position and walking away with content for their resumes from the positions in which they were most active. We interviewed every student, regardless of whether their paperwork had been accepted by the WorkSource centre, to establish the understanding that all would be eligible provided their applications were complete and submitted in a timely fashion.

Before the internship began, we set clear expectations for our interns. First, students needed to turn in all required documents. Unfortunately, this proved to be a barrier to entry in and of itself since the list of required documents was long and inclusive. An entry from July 1, 2019, in my ethnographic journal states: “The youth must present a W4, I9, birth cert, signed copy of a social security card, proof of residence (18+), work permit (under 18), signed library card, school ID, job application, selective services registration (18+), and copy of a parent’s photo ID (under 18)” (M. Lipset, personal communication, July 1, 2019). For some students facing barriers such as houselessness and criminalization, presenting documentation proved challenging. Still, identifying factors that may have prevented our students from getting hired elsewhere, such as a criminal record or undocumented status, were not obstacles. In this way, we were able to provide paid internships to young people whose opportunities for work had already been greatly reduced by the criminalization system and international borders, neoliberal structures that serve to separate, isolate, and segregate people based on difference. Since a number of our students were unable to produce the required documents, we hired only 15 students for the available 22 positions, which meant we filled 68% of the positions and hired 54% of our total classroom-based students.

Second, our students would only get paid for the hours they worked and had to document their own timesheets. By establishing work hours for students, we introduced an employer-employee dynamic, which conformed to neoliberal notions of power and hierarchy within professional fields. However, we gave students control over almost every other creative aspect of the work wherever possible to promote autonomy and dialogical decision-making.

Once the internship began, students set out to promote their first collectively written and produced album. Songs on this album covered topics ranging from false narratives surrounding Christopher Columbus, the displacement of Latinx communities for the construction of the Los Angeles Dodgers’ stadium, and our school’s theme song, to other topics that sought to critically deconstruct academic topics in artistic and social justice-oriented ways. During the internship, students gathered over 1,200 media contacts; wrote press releases for three separate artistic products; designed album covers for each; wrote and recorded a promotional song; shot and edited a video for that song; wrote, recorded, produced, and disseminated radio ads for each product; promoted music videos for their first and second singles; and gave the keynote performance at the world‑renowned Deeper Learning Education Conference in 2019. By the end of the internship, our students were invited for a studio interview and performance at the legendary BeatJunkies radio station to promote their work.

Throughout the process, our teachers credited students for much of the work they did on behalf of the record label. Students received English credit for the written work they produced in their professional emails and press releases. Students received math credit through an algebra project focusing on creating graphable functions of the amount of money each major music-streaming platform pays its artists per play. Students also received economics credit for analyzing the monetary and non-monetary incentives available to them as artists.

During the internship, a record label executive at HSRA, St. Paul, Minnesota, remotely co-facilitated our interns in collaboration with one of our local instructors, schooling the students formally in the daily tasks of the industry. Students worked back and forth between the recording studio and the pre-production room where we hosted the internship, engaging with our studio facilitators to apply the knowledge they had learned in the recording arts during creative parts of the internship. As a teaching team, we nurtured our students’ abilities to thrive in the world as creative professionals, converting us as educators into creative pedagogues through partnerships among ourselves and our students in addition to partnerships with community-based organizations like those mentioned earlier. Through the artful instruction of creative practices and processes, we stepped into the role of teaching artists, fulfilling that portion of the role of a creative pedagogue.

Some unavoidable challenges made it difficult to establish consistency and momentum at the beginning of the internship. We name these here for those considering starting similar programs. The WorkSource centre initially had assured us our site could begin logging our interns’ hours by the start of the second week of Trimester 3. Unfortunately, they took an extra 1.5 months to process our students’ paperwork, delaying the students’ first paychecks an extra 45 days and leaving only one month to log and process their hours. Although we began the internship in the second week of Trimester 3 and planned to backdate student timesheets to match hours worked, the absence of a timely paycheck was a serious disincentive to our students. Nevertheless, visits from the WorkSource centre’s site manager helped maintain the sense that the internship was real, and hours ultimately would be compensated.

FINDINGS

Despite these challenges, certain outcomes suggest possibilities for future schools to benefit from similar programming and the repositioning of adults in the school from teaching artists, teachers, and administrators to creative pedagogues. Such outcomes include evidence that students gained an improved sense of financial management, earned more academic credit over the course of the trimester, and were more drawn to enrolling in and attending school itself. For example, a review of my own ethnographic journal indicates that, for many of our students, this job was the first time they had ever received an official paycheck or opened a bank account. In my July 1, 2019, reflection, I wrote, “Many asked questions about how to cash a check, how to open a bank account, and when paychecks would arrive next” (M. Lipset, personal communication, July 1, 2019).

As school leader, my responsibilities shifted from those of an administrator to those of a creative pedagogue, a much more dynamic role. My duties as an administrator primarily included coaching our core content instructor, coaching our studio facilitators, insuring collaboration between our core content instructor and studio facilitators, tracking metrics like enrolment and attendance, guiding school culture, engaging in regular transformative justice practices, promoting our school to the community, tracking overall student progress, building strong relationships with families, managing our many social service offerings (such as free clothing/toiletries and housing support), inviting guests to the school, and maintaining mission-orientation. Through the internship, however, I became involved more directly in student learning by building partnerships between the studio, the classroom, and our flagship school in Minnesota. As activities from the internship spilled over into the rest of the school day, I became involved in supporting our team in navigating how to adjust their teaching practices to remain rooted in social justice, the instruction of careers in the creative industries, and to do so through partnerships with relevant organizations.

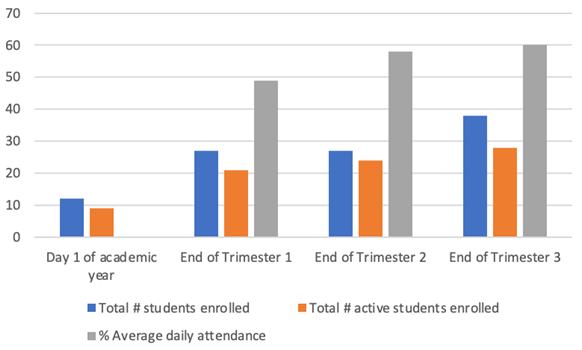

Though data do not point to clear causation with regard to enrolment and attendance in response to the internship, findings suggest a positive correlation may exist. Of the new students who enrolled in Trimester 3, each had been referred by a parole / probation officer, social worker, community organizer, or friend who was already familiar with our program. Figure 2 shows enrolment and attendance numbers over the course of the year.

FIGURE

2. Enrolment

and average daily attendance by trimester at HSRA LA for academic

year 2018−19

FIGURE NOTES. Figure 2 shows the difference between growth in enrolment over the course of the school year in three areas: 1) Total students enrolled, which is the total number of students enrolled, both active and inactive. 2) Inactive students enrolled refers to the students who left after enrolling or were unable to return. 3) Average daily attendance represents the percentage of active students who actually showed up on any given day out of total enrolled. Among re-engagement schools, national trends for average daily attendance range from 50%–60% (Moore, 2016).

The same social workers and youth workers from the community brought new students to our program and mentioned our internship offerings as a hook when touring our school with their youth during Trimester 3. This trend suggests they saw the internship program as a powerful opportunity to engage their youth and underscores the importance of a creative pedagogue as connecting the school to the community. Through presentations of our internship program and school offerings to administrators at the Department of Child Foster Services, Parole and Probation Offices of Los Angeles, and the Gang Reduction Youth Development Task Force of Los Angeles, we were able to attract more students by building relationships throughout the community in line with the work of creative pedagogues. My journal entry from April 21, 2019, reads:

I presented to [a community organization] a few weeks ago … they have since been sending us students. Still, the best way for students to get in the door is by word-of-mouth and thus far, that has been our biggest asset in terms of recruitment. (M. Lipset, personal communication, April 21, 2019)

Each service referred a number of students to our program throughout the year with Trimester 3 showing the largest increase in our total enrolment of 11 new students. Perhaps the most important indicator of impact from the time of the internship, however, was an increase in the number of hours students spent on campus overall, which resulted in increased time each student spent in academics. By the end of Trimester 3, all but two of our interns earned more credits during Trimester 3 than in the first two trimesters.

Discussion

One of our biggest concerns when starting this internship program lay in its reinforcement of neoliberal justifications for education (i.e., that learning should be done in service of securing a job or financial stability). Such concerns are warranted, and we as a staff agreed that learning should be revered as the worthy endeavour we expect from young people generally. Nevertheless, our students’ strained financial circumstances played a role in preventing them from accessing opportunities to learn. If students’ circumstances are such that they are having trouble accessing education without increased financial security, especially because of systemic forms of violence such as racism or classism, combining paid work and education only makes sense. We felt our students in particular deserved access to the funds provided by the WIOA program. Furthermore, although the income generated for our students through this program meant a tremendous amount for them, students could only earn $1,590 pre-tax. We did not compensate their education to the degree that their schooling on the whole could have been seen as valuable only as paid work. I believe the outcomes of our student-run record label show that the opportunity to gain professional experience in creative industries in conjunction with education increased our students’ general academic engagement as evidenced by changes in student attendance, credit accrual, and enrolment during Trimester 3.

As creative pedagogues consider similar programming, they should heed lessons learned here through partnering with state-based bureaucratic systems like America’s Job Corps, which took extra time to process student applications. For example, since consistent timing and the start-date of an internship program may impact how students perceive the internship within their broader schooling experience, ample planning time should be allowed for the successful launch and consistent execution of important human resource processes like issuing paychecks, processing applications, and gathering the appropriate application materials. How organized the internship provider / school appear(s) to the students may impact how seriously students take the opportunity, an area deserving of further research.

Neoliberal understandings of power, privilege, wealth, and individualism have historically served wealthier, White individuals and their organizations to the detriment of the working class and students of colour. Yosso (2005) argues the value systems that accompany these mechanisms take precedence in traditional school settings but should be replaced with the kinds of cultural capital germane to students from communities on the receiving end of systemic forms of violence. This internship program, in its entirety, represented a counter-hegemonic approach to education in the creative industries. With our students, we actively worked to combat neoliberal tropes of individualism by cultivating a shared vision for the workplace, empowering students to own their collective work and to imagine how they might use their new skillsets in the future. Our work fell within the lines of what Campbell (2013) found to be true of similar, non-credit granting, arts-based work programs: “Economic development can be understood not only as individual interpersonal work, but part of a broader social justice mandate of self-determination and economic self-realization, in particular for marginalized youth” (p. 174). Findings suggest this internship increased student re-engagement by bringing more out-of-school youth back into a high school setting that operated with an ethos of social justice-oriented, anti-oppressive educational practices. We were confident in our ability to do so since our education program had already been designed to instruct for critical consciousness and in opposition to the kinds of education programs that had left our students disaffected and pushed out in the first place. Schools that have not produced an anti-oppressive curriculum and school culture should not work to re-engage students at all, much less through an internship program like the one described here. Doing so would subject them to the same damaging cycles that already pushed them from school.

The student-run record label internship program stood in stark contrast to the historically exploitative relationship held between record label companies and artists, which, in Hip-Hop especially, often sees artists of colour creating work that garners more money for White record label executives than for the artists themselves (Rose, 2008). In the case of our student-run record label, all proceeds went to the students, who were also the artists and who also had creative control over their work. In this way, the student-run record label reversed the historically exploitative relationship between Hip-Hop artists and their record labels by placing control over every aspect of the artistic and industrial processes in the hands of the students. By placing students at the centre of both the creative and entrepreneurial processes, we were able to support students in developing their entrepreneurial skills by harnessing their artistic talents. Rather than making art for art’s sake, our students had to consider art for the sake of the whole label’s wellbeing (i.e., their peers). We pushed students to think about such components of Hip-Hop culture as improvisation and creativity as tools to be used for the promotion and dissemination of their art and their social justice initiatives / statements.

With some work, such a program may be possible at many schools. If the school is not in LA but within the US, further exploration of the specifics of the WIOA program in a given location may be required. Starting something like this program outside of the US means first determining whether students can be paid while attending school and receiving credit. If a local government does not allow such an opportunity, hopefully this paper encourages decision-makers to pursue changes in legislation that would allow such an opportunity, at least for those students who historically have been underserved by the education system.

The existence of systems supporting paid, for-credit internship programs on school campuses in both the US and Canada adds evidence to the important work of creative pedagogues. In Canada, for example, where education policy exists on a provincial level, the following programs support student internships: The PATHS program in Manitoba focuses on providing opportunities for young people to pursue careers in the automotive industry for pay and high-school credit (Council of Ministers of Education, 2015, p. 45). The Apprenticeship Credits and Saskatchewan Youth Apprenticeship for Recognized Trades provides credit for career training and paid work in Saskatchewan (Council of Ministers of Education, 2015, p. 35). The Ontario Youth Apprenticeship Program (OYAP) is available only to full-time 11th and 12th graders ages 16 and up who are interested in skilled trades (Council of Ministers of Education, 2015, p. 57). The Youth Apprenticeship Program in Newfoundland and Labrador is designed to grant high school and post-secondary credit to students interested in pursuing a trade in their last year of high school (Council of Ministers of Education, 2015, p. 75).

Although each program identifies increasing secondary school completion as a core goal, the aforementioned programs have only focused on the trades. None provides opportunities for paid, for-credit career exploration on campus that might increase attendance and reduce barriers to entry for students who have trouble attending school as a result of having to find paid work. Furthermore, very few career paths supported through the programs align with the creative industries despite rapid growth in interest in careers in the creative industries (Campbell, 2020, p. 2). However, each such program has posted notable increases in high school completion for students involved (Council of Ministers of Education, 2015). Though none of these programs focuses on underserved youth, they do provide credit to young people for work off-campus and confirm that students in Canada can receive credit for paid work. It may be possible, therefore, for young people to participate in something similar to what has been described here in certain Canadian provinces. For example, skilled trades in Ontario include titles like “special events coordinator” and “entertainment industry power technician,” roles that, when put together, could provide creative pedagogues with incredibly rich learning opportunities, for example, to engage young people in planning and producing their own music festival (OYAP, 2019). The OYAP also includes “hairstylist” as a supported position, which would allow for creative pedagogues to come together in support of a student-run, on-campus youth barber / beauty shop.

Our program was possible because of a unique confluence of partnerships that may be difficult to develop elsewhere. For schools interested in doing so, partnering with an organization specializing in a vocation that students find engaging and that matches the mission of the school seems crucial. Grantmakers interested in funding a program may also serve as the accounting department for a school’s newly hired interns, or a school could partner with an additional organization, something akin to our local WorkSource centre, to play the same role. Whether or not paid on-campus and for-credit internships exist in each location, the opportunity for school staff to shift towards the role of a creative pedagogue always does. The arts, education, social justice, and community partnerships can still align to produce powerfully engaging learning opportunities for young people and present new and exciting opportunities for students to prepare themselves for life beyond high school.

Summary

Findings suggest the pairing of paid internship programs for academic credit produced powerful learning incentives for opportunity youth. Students came to school more regularly, were drawn to our school for such an offering, and earned more academic credit during the internship than in previous trimesters. Students developed their ability to design and develop their own professional spaces, particularly in creative industries, learning practical life skills along the way. Furthermore, as school leader I felt an identified shift in my role towards that of a creative pedagogue, which facilitated deeper learning opportunities for students. If a school serves young people whose access to education is hindered by the necessity to find paid work, educators and policy makers should consider developing paid internship experiences that also offer opportunities to earn credit on campus.

The arts should be central to student learning, especially at the re-engagement level, where addressing basic student needs of safety and care commonly supported by the arts exist alongside developmental needs like increased self-esteem and self-knowledge. These needs can be supported by successful professional work, especially in the creative industries given the therapeutic nature of the arts.

Further research on the impacts of paid internships for opportunity youth could shed light on a number of important approaches to increasing the re-engagement of out-of-school youth. For example, the internship as occurring over the course of 10 weeks, with the first and last hour of each day as paid hours, seemed to increase student engagement over the course of a trimester. While internships have been documented in the field of construction, other such trades as the creative industries deserve the same opportunity for research. Until the greater mechanisms of society change to level the playing field for low-income and youth of colour, policy makers and change agents should work to incorporate paid internships into their academic programs with the combined goal of empowering young people to advocate for the world they want to live in. Given increased interest by students in creative professions, educators and policy makers should consider paid internships in creative industries central opportunities for learning important life skills within an ecosystem of learning. Instead of cutting the arts from schools and marginalizing work in the creative industries, the arts and careers in the creative industries deserve more structural support within systems of education to set today’s youth up for success in fields of their choosing.

References

Akom, A. A. (2009). Critical hip hop pedagogy as a form of liberatory praxis. Equity & Excellence in Education, 42(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665680802612519

Alim, H. S. & Paris, D. (2017). What is culturally sustaining pedagogy and why does it matter? In D. Paris & H.S. Alim (Eds.). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world (pp. 1–25). Teachers College Press.

Anyon, J. (1997). Ghetto schooling: A political economy of urban educational reform. Teachers College, Columbia University.

Baldwin, J. (1962/1998). The creative process. In T. Morrison (Ed.). James Baldwin: Collected essays (pp. 669–672). The Library of America.

Belfield, C. R., Levin, H. M., & Rosen, R. (2012). The economic value of opportunity youth. 1(1), 1–49. The Corporation for National and Community Service and the White House Council for Community Solutions.

Booth, E. (2009). The music teaching artist’s bible: Becoming a virtuoso educator. Oxford University Press.

Cairns, K. (2013). The subject of neoliberal affects: Rural youth envision their futures. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien, 57(3), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12012

Campbell, M. (2020). ‘Shit is hard, yo’: Young people making a living in the creative industries. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 26(4), 524–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2018.1547380

Council of Ministers of Education, Canada. (2015). Toolkit of promising practices that assist in the alignment of skills and education systems with the needs of the labour market. https://www.cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/349/Toolkit_jan15-2016_EN.pdf

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). New standards and old inequalities: School reform and the education of African American students. Journal of Negro Education, 69(4), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.2307/2696245

Emdin, C., & Lee, O. (2013). Hip-hop, the "Obama effect," and urban science education. Teachers College Record, 114(2), 1–24.

Escudero, P. V. (2019). Los Angeles Unified School District Student Health and Human Services: Reference guide 2019–2020 Opening day procedures: Supplemental guide and updates. Los Angeles Unified School District. http://www.lausd.net/cdg/PupilServices/6767/story_content/external_files/REF%206767%201%20LAUSD%20CAMPUSES%20AS%20SAFE%20ZONES%20AND%20RESOURCE%20CENTERS.PDF

Gardner, H. (n.d.). Passion tempered by discipline. Unpublished remarks to the AIE Advisory Council. Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Gaztambide-Fernández, R. (2013). Why the arts don't do anything: Toward a new vision for cultural production in education. Harvard Educational Review, 83(1), 211–237. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.83.1.a78q39699078ju20

Gee, C. B. (2004). Spirit, mind, and body: Arts education the redeemer. In E.W. Eisner & M.D. Day (Eds.). Handbook of research and policy in arts education (pp. 115–134.) Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers.

Ginwright, S., & Cammarota, J. (2007). Youth activism in the urban community: Learning critical civic praxis within community organizations. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education (Qse), 20(6), 693–710.

Gould, D. & Co. (2005). Media paints arts education in a fading light. Education Commission of the States. 1–17. https://www.ecs.org/clearinghouse/63/75/6375.pdf

Hill, M., & Petchauer, E. (Eds.). (2013). Schooling hip-hop: Expanding hip-hop based education across the curriculum. Teachers College Press.

Hossain, F. (2015). Serving out-of-school youth under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (2014). MDRC. https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/Serving_Out-of-School_Youth_2015 NEW.pdf

Ibrahim, A. (2004). (Popular) culture matters - Operating under erasure: Hip-hop and the pedagogy of affective. Jct, 20(1), 113–134.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2017). The (r)evolution will not be standardized: Teacher education, hip hop pedagogy, and culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0. In Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (Eds.). Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world (pp. 141–156). Teachers College Press.

Lipman, P. (2004). High stakes education: Inequality, globalization, and urban school reform. RoutledgeFalmer.

Love, B. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

Love, B. (2015). What is hip-hop-based education doing in "nice" fields such as early childhood and elementary education? Urban Education, 50(1), 106–131. https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1177%2F0042085914563182

Moore, A. O. (2016). Reengagement: Bringing students back to America’s schools. Rowman & Littlefield.

Morris, M. W. (2016). Pushout: the criminalization of black girls in schools. New Press.

Nathan, J. (1996). Charter schools: creating hope and opportunity for American education. Jossey-Bass.

Ontario Youth Apprenticeship Program: Trades at a glance. (2019). https://oyap.ca/en/skilled_trades/trades_at_a_glance

Orlowski, P. (2011). Teaching about hegemony: Race, class and democracy in the 21st century. Springer.

Parsons, T. (1964). Social structure and personality. Free Press of Glencoe.

Petchauer, E. (2009). Framing and reviewing hip-hop educational research. Review of Educational Research, 79(2), 946–978. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0034654308330967

Rodriguez, L. F. (2009). Dialoguing, cultural capital, and student engagement: Toward a hip hop pedagogy in the high school and university classroom. Equity & Excellence in Education, 42(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665680802584023

Rose, T. (2008). The hip hop wars: What we talk about when we talk about hip hop— and why it matters. BasicCivitas.

Seidel, S. (2013). Exploding parameters and an expanded embrace: A proposal for the arts in education in the twenty first century. Harvard Educational Review, 83(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.83.1.q8q24t6859494833

Seidel, S. S. (2011). Hip hop genius: Remixing high school education. Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Tamer, M. (2009). On the chopping block, again. In Ed. Magazine. Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Tyack, D. B., & Cuban, L. (1995). Tinkering toward utopia: a century of public school reform. Harvard University Press.

United States Department of Labor: Employment and Training Administration (2019). Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act: WIOA program. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/youth/wioa-formula

Wong, C., & Pena, C. (2017). Policing and performing culture: Rethinking “culture” and the role of the arts in culturally sustaining pedagogies. In Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (Eds). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world (pp. 117–138). Teachers College Press.

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/1361332052000341006