FIGURE 1. Overview of Story Map

EXPLORING THE CREATIVE GEOGRAPHIES OF WORK WITH PRE-SERVICE SOCIAL STUDIES TEACHERS: EXPOSING INTERSECTIONS OF TIME AND LABOUR IN NEW BRUNSWICK, CANADA

CASEY M. BURKHOLDER & ALLEN CHASE University of New Brunswick

Engaging in the labour of teaching has always been political and draws on creative capacities. Among the purposes of designing meaningful and critical assignments for pre-service teachers is the desire to create opportunities for learning, and for pre-service teachers to imagine incorporating similar practices in their own teaching. Given the unlimited range of creative pedagogies that professors of pre-service teachers have, garnering learners’ intrinsic desire to learn for the sake of learning, as well as fostering an awareness of potential agency towards teaching for and about social justice issues through creative inquiry, provides the didactic purpose of pedagogy. Challenging pre-service teachers to critically reflect upon their sense of agency and their role in systems reproduction is an essential and necessary task. By positioning the professor as a co-learner in a social justice and agency dialectic, co-learning has the potential to flourish from the ground-up (Choudry & Kapoor, 2010; Freire, 2018). In this kind of a classroom, the teacher-student paradigm is modified from being a traditional top-down experience to an engaged exploration of social justice issues where teaching is positioned as a kind of activist practice within a local context — addressing inequities in both schools and society. Together, we wonder, how might pre-service teachers engage deeply and creatively with pressing political issues in the Geography classroom (racism, inequality, labour conditions, late-period capitalism, settler colonialism) in the context of New Brunswick, Canada, and how might this engagement be assessed?

In this article, we reflect on an example of co-learning creative pedagogical approaches by developing multiple interconnections between artmaking (positioning an assignment as art-production) coupled with critical inquiry into the geographies of work in New Brunswick. In this article, we describe an assignment where a class of pre-service teachers, enrolled in a Bachelor of Education degree program with a concentration in social studies, learned about the inexorable intersections of time and work with real-world experiences. Through this assignment, Burkholder sought to politicize the ways in which work — including the work of teaching — is seen and unseen with an eye toward promoting teacher agency and engaging in teaching for social justice. The example herein shows how a pair of pre-service teachers (Allen and his collaborator) reconceptualized their role as prospective teachers in terms of the political potential of engaging students with social justice issues by examining how work and time intersect by mapping a worker’s day. Creative pedagogies such as narrative map-making, cellphilm production (cellphone + filmmaking, see MacEntee et al., 2019), and researching the ways that labour and time intersect through work all require a reflection upon the synthesis of work, time, and the alienating and exploitative nature of labour in today’s late-period, neoliberal, commercialist, and capitalist society. We see our work together as an example of collaboration, of creating solidarities, and of examining as well as addressing inequalities within labour and in teacher education, in response to the neoliberal political status quo.

SITUATING OUR INQUIRY IN RELATION TO THE COURSE

The Introduction to Geography in Education course was intended for secondary pre-service Social Studies teachers to begin to think about the practice of teaching geography: inclusive of ideas about place, space, time, geography, humans, and the Anthropocene — the present geological era where human behavior has irreparably shaped the physical environment (Lewis & Maslin, 2015). The goal of the course was to encourage students to become reflective and inquisitive geography educators, by critically investigating Social Studies & Geography curricula, Grades 6–12. We reflected and extended upon existing curricular concepts and engaged in multiple ways of knowing and experiencing along the way. The course focused on exploring geography within and beyond maps (i.e., exploring and representing space, time, humans, art, actions, and the environment) while conceptualizing them as inherently political projects. In choosing the course textbook, Katherine McKittrick & Clyde Woods’ Black Geographies and the Politics of Place, Casey sought to disrupt the ways that European settler geographies have been foregrounded in the teaching of Social Studies and Geography in the context of New Brunswick. The erasure of Black peoples’ and Indigenous peoples’ histories and geographies from New Brunswick Social Studies and Geography curricula encourages the state project of anti-Indigeneity and anti-Black racism (Adjei, 2018; Maynard, 2017). Throughout the course, Burkholder worked to disrupt the apolitical teaching of geography and the erasure of Wolastoqiyik, Mi’kmaq, Passamaquoddy, Abenaki, Penobscot, and Black Atlantic Canadians’ histories and geographies with creative pedagogies. Through the reflection and production of stories, images, and videos, we worked to capture the ways that political and dystopic geographies exist in Atlantic Canada, especially around environmental injustices related to resource extraction and fracking, racial injustices in the name of progress (e.g., gentrification and dispossession in Nova Scotia from Africville to the present), and reproductive injustices through barriers to access to reproductive health services for trans, non-binary people, and cisgender women.

Regular course practice consisted of field trips, such as exploring liminal spaces along back alleyways, and exploring the local high school’s “hill” where illicit activities were said to take place. We also watched films: Thom Anderson’s (2004) visual essay Los Angeles Plays Itself, that shows the ways the city of Los Angeles has been depicted visually within Hollywood cinema, and Lisa Jodoin’s (2014) short Tracing Blood, which explored her identity as an Indigenous woman responding to the “Are you native?” question. We began by thinking deeply about space within our local context. How is space constructed? What about time? How do humans interact in spaces and with time? How are these experienced in relation to racial, ethnic, sexual, gendered and (dis)abled identities? How are space and time constructed in schools and society? What can we learn if we think about these space and time in political terms? How are cities, territories, rural areas, and nations constructed in film / media? How are people that occupy these spaces constructed in relation to the spaces? What makes a Maritimer a Maritimer? Or a New Brunswicker a New Brunswicker? What do these constructions tell us about racial, ethnic, sexual, gendered and (dis)abled identities? These guided questions served to creatively anchor our inquiry into local geographies and the ways in which spaces and places shape our behaviors and actions.

Together, in this article, we reflect on an assignment where pre-service teachers were asked to map a worker’s labour for a day. The purpose of the assignment was for pre-service to explore the extent to which labour separates and connects people in the city and province in ways that are largely invisible, and intersected by issues of gender, class, race, ability, and sexuality (Crenshaw, 1989). The assessment was adapted from an assignment developed by Dr. Shannon Walsh at the School of Creative Media (City University Hong Kong) in Winter, 2015 and refocuses the assignment toward the geographical particularities of New Brunswick in Spring 2019. The questions that have driven this inquiry are influenced by our experiences as professor (Casey) and as former pre-service, now in-service teacher (Allen):

How might looking at work and labour encourage pre-service teachers to creatively engage with social critique and action?

What can we learn about work, labour, space, capitalism, and intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) by mapping a worker’s day?

How might visual inquiry, as a creative pedagogical practice, encourage pre-service teachers to think about and perhaps even take political action?

POSITIONING OURSELVES IN THE STUDY

Positioning ourselves in relation to the study is necessary to situate our understandings, as feminist and post-colonial theorists have long argued about, and the politics of speaking for [and about] others (Alcoff, 2009). Alcoff argues that a researcher must contend with the social spaces where both the research and the discursive acts within the research are taking place.

Following Foucault (1975/1995), I will call ‘rituals of speaking’ the discursive practices of speaking or writing that involve not only the text or utterance, but its position within a social space which includes the persons involved in, acting upon, and/or affected by the words. We focus on two elements within these rituals: the positionality or location of the speaker and the discursive context (p. 121).

This work is especially important in locating us spatially and geographically as two people who have directly benefitted from the state project of European Canadian settler colonialism.

We write together as a professor of an Introduction to Geography in Education course (Casey) and as a former student of the course (Allen). Though she has been teaching in postsecondary institutions for the last five years, Casey has recently begun to really think about what she is doing in her work as a teacher educator in terms of systemic reproduction and furthering oppression. She had previously thought that her work with pre-service teachers to see and expose inequalities in schools and societies was making a difference in her local educational contexts. Over time, she has become a little disillusioned with this work. Looking around her, Casey has noticed that the world is on fire, both literally (Kyle, 2019) and in relation to the erosion of people’s rights and freedoms (O’Donnell, 2019). To what extent does her work in teacher education replicates the oppressive systems and structures that she, as a white middle class cis femme, has benefited from? Throughout the Introduction to Teaching Geography class, she focused the class inquiry on the issues that she was most concerned with living ethically in the Anthropocene, confronting anti-Black racism and anti-Indigeneity, petrocapitalism, institutional geographies of patriarchy, exploring liminal spaces and noticing slow violence, such as the environmental catastrophes that build up slowly over time and hardly make the news (Nixon, 2011). These themes arose throughout the course, and she endeavored to bring them through the course assessments.

As a recent graduate of a Bachelor of Education degree program and former graduate student in political science, Allen is particularly interested in how educators develop critical consciousness in the process of thinking dialectically (Freire, 2013; 2018). Educators face the challenge of bridging the gap between theory and praxis on a daily basis: some educators are conscious of their reflective action and critical theorizing, while others reject them criticality. Following the “Freirian” message of immersing the educator with the learner as a co-learner in a dialectical process toward conscientization is part of the critical and necessary elements in education. The extent to which educators are problematizing the status quo, as well as challenging historical and cultural realities, generates a same-order-of-magnitude space where learners (and educators) begin to experience praxis in itself (Freire, 2013). Allen is troubled by the deeply ingrained bureaucratic systems that support our society’s neoliberal and capitalist structure, especially in systems like public education. Drawing from Marx’s economic and political philosophy, the critical philosophy and social theory works of the Frankfurt School’s political philosophers (Horkheimer, Adorno, Marcuse, etc.), and Hannah Arendt’s breadth of work drawn from the ancients on the human condition, the inherent crises of capitalism in our late-modern world (f) call for immanent attention and action. The importance of educating learners within a critical consciousness dialectic helps combat the inevitable process of alienating students’ experience of knowledge as a commodity. “School makes alienation preparatory to life, thus depriving education of reality and work of creativity” (Illich, 1971, p. 47). Allen is interested in exploring how teachers adopt, accept, and embrace critical consciousness (in teacher education) and implement it in their own classes. He is similarly interested in an exploration of how critical consciousness is lost, whether by the nature of their work and profession or as a process in an alienating, bureaucratic, and technocratic environment.

We bring our experiences, and frustration with the neoliberal status quo to our inquiry here.

POLYVOCALITY: A METHOD FOR CO-WRITING

We have negotiated ethical tensions within our collaboration as we have moved from the positions as professor and student to our ongoing collaboration as co-writers (Sultana, 2007). Through an examination of multicultural women’s writing, Nayak Kishori (2009) has argued that polyvocality, or the use of many voices writing together, is a “pluralist and transgressive” (p. 46) feminist writing practice. We employ a polyvocal approach in the writing of this article to address the power imbalances within the research, particularly when reflecting on the work that Allen had previously submitted for assessment. Kathleen Pithouse-Morgan et al. (2015) describe the “critical introspection and shared vulnerability” (p. 163) that can be drawn out in the polyvocal process. We see our polyvocal collaboration as an extension of critical geographical practice: creating space in writing together in order to get at the tensions of mapping work and labour. It is our intention to shift our creative pedagogies toward writing collaboratively and disseminating our thoughts in academic spaces by employing a polyvocal approach to writing this article (Pithouse-Morgan et al., 2017).

THEORIZING OUR INQUIRY

The conceptual framework for our inquiry draws upon intersectionality — the ways in which social categories (e.g., race, class, gender) are experienced relationally, rather than independent of one another (Crenshaw, 1989; 1991), which we have seen through our examination of the political nature of work and space and movement. Our practice of working together to look back on the assignment engages with theories of critical civic engagement (Buckingham, 2009; Buckingham & Willet, 2013; Fox et al., 2010; Gordon, 2008; Harris, 2012). Adding criticality to an understanding of citizenship is integral to this study as much of the citizenship literature’s canon. For example, Marshall, 1977 and Turner, 1990 present theories of citizenship without careful attention to intersectional issues, but these notions have clear implications for citizens that cannot be mapped within dominant, hegemonic majorities. We also frame our inquiry through an examination of labour and time in relation to Marxism (Carver & Harris, 2019; Marx & Engels, 1978). Drawing on the work of Schratz and Walker (1995), de Lange (2012) takes a “research as social change approach” and argue that working “deeper and not wider” in communities may encourage both project sustainability and social action (p. 324). Casey takes a similar approach in her teaching: drawing on the tenets of participatory visual research methodologies, she works with learners, as co-researchers, to investigate society deeply. By employing participatory approaches and working with pre-service teachers to look deeply at inequality and oppression to identify changes that they would like to see in their own communities, Casey has endeavored to put social action at the fore of this assignment and in our writing together. We see this inquiry as critical within the creative practice of teaching and learning.

Critical thinking is a tool for self-determination and civic engagement (Freire, 2018; Giroux, 2017). Critical pedagogy provides students with the opportunity to learn from a position of agency. In this view, teachers should strive to establish safe classroom environments where students are given the opportunity to raise problems and to question the dynamics of power and authority; students are provided with more control over the conditions of their learning based on these classroom relations (Giroux, 2017). In order to help avoid the perpetual replication of the capitalist and neoliberal status quo in education, critical pedagogues should aim to inherently reject the systems of educational rationalization that are oriented around market capitalism, instrumentalized knowledge, and technocratic “culture industry” over creativity, imagination, and critical thinking (Adorno, 1998). Assignments that highlight the intersections of work and labour, such as engaging students with workers in a community, fosters a dialectic of critical consciousness among students, pedagogues, and the local communities of work.

Bridging the gap between theory and praxis is one of the aims of critical pedagogy. The didactics of critical pedagogy by teachers with students is, arguably, one of the most important aims of teaching. One way to teach critical theory is by having students work with teachers on finding and establishing educational contexts to address social issues by means of critical studies and analysis (Rogers, 2017). One such method of engaging students in critical studies is through creative and participatory media making — including documentary filmmaking and cellphilming. Film as text-making allows for a critical context for engaging in real-world explorations of topics to teach for and about equity and social justice. Simultaneously, the teacher becomes an active participant in the co-learning process. Without ever explicitly outlining critical pedagogy to students, teachers have the opportunity to create authentic learning in the pursuit of students’ agency through participatory filmmaking.

Learning alongside students highlights the intricacies of power and agency dynamics, relationships of authority, and developing a consciousness of freedom in the pursuit of social justice and equity, is the dialectical purpose of what Freire (2018) calls “an instrument for critical discovery” — or the pedagogy of the oppressed (p. 48). In an era of the besiegement of public and higher education by conservative and neoliberal forces (Giroux, 2017), educators have the potential to form part of the frontline to hold off market-driven changes to education. If the purpose of education is a “purpose of freedom” (Giroux, p. 154), then critical pedagogy must be connected to social justice and equity.

RESISTING APOLITICAL APPROACHES TO GEOGRAPHY EDUCATION: CENTERING JUSTICE AND SPACE

The assignment

The guidelines of the Geography assignment we reflect upon was to get pre-service teachers to create a Story Map containing up to 10 data points which locate the movements of a worker in the span of one working day. Pre-service teachers were also tasked with creating a cumulative analysis of their inquiry in the form of a narrative cellphilm (cellphone + film production, see MacEntee et al., 2019). The purpose of the assignment was to understand the extent to which labour separates and connects people in a city in ways that are largely invisible. Pre-service teachers were expected to seek out someone whom they feel holds the city together through their work and follow that person throughout their working day. In the process, the pre-service teachers created a topological map of data points with supporting photos and descriptors. The assignment’s purpose was also to demonstrate the interconnected relationship between workers and the city’s environment. Furthermore, the assignment aimed to synthesize the intersections of where work happens, and who benefits from the work. Casey aimed to challenge pre-service teachers’ sensibilities about how the assignment might politicize work, and make visible the economic implications of work (how the work minimizes labour concerns). Some questions she wished to encourage pre-service teachers to consider included: how is work conducted on unceded / unsurrendered territories? How does work intersects with settler colonialism, land, appropriation of traditional territories, and dispossession? Ultimately, the assignment sought to challenge future Social Studies teachers to consider how they might use a similar assignment with their own students.

The assignment description read:

Cleaners, dishwashers, taxi drivers, cooks, childcare workers, domestic builders, plumbers, sanitation workers, construction workers, bankers, bartenders, and sex workers make the city. In this group assignment (2–5 students), students must find someone who they think holds the city together through their work, and follow that person, creating a map and visual story of who and what depends on their work. The result is that each student’s topological map will be placed in relation to other students’ maps, ultimately producing one large class map showing the complex and interconnected relations between people in the city.

Students were guided to choose a worker to follow for the day, and to map their labour’s coordinates using a software program called StoryMaps. StoryMaps is a software program that encourages the integration of storytelling and visuals with coordinates on a map. Providing at least 10 data points and at least 10 photographs or visuals, pre-service teachers were asked to create a story that explained the worker’s workday journey and the ways that their labour contributed to the city or Province. What follows is a reflection on an example of a StoryMap involving one pair of pre-service teachers (Allen and his Collaborator) and their analyses while completing the assignment.

Mapping intersections of time and labour through the example of a delivery truck driver’s work

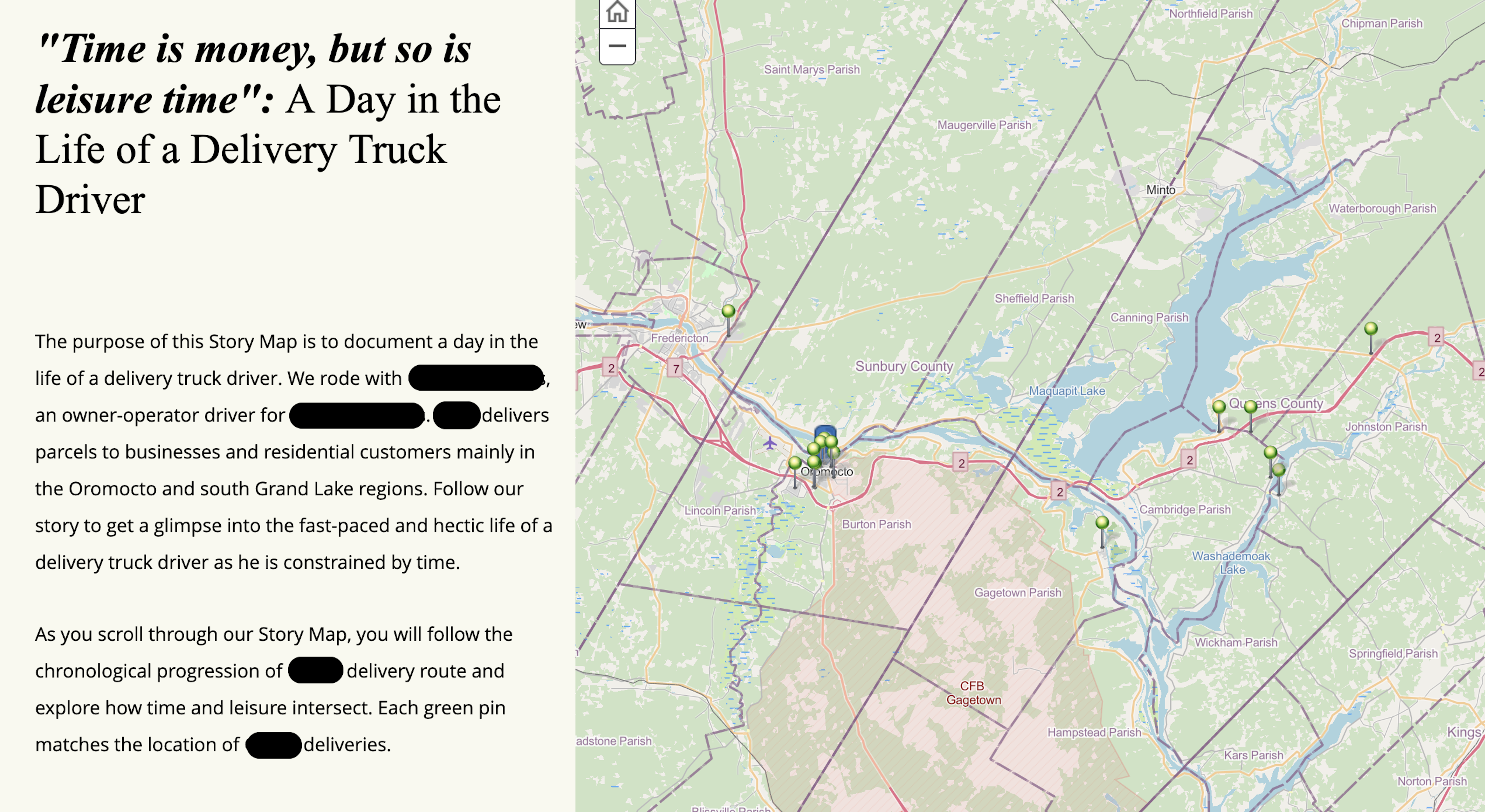

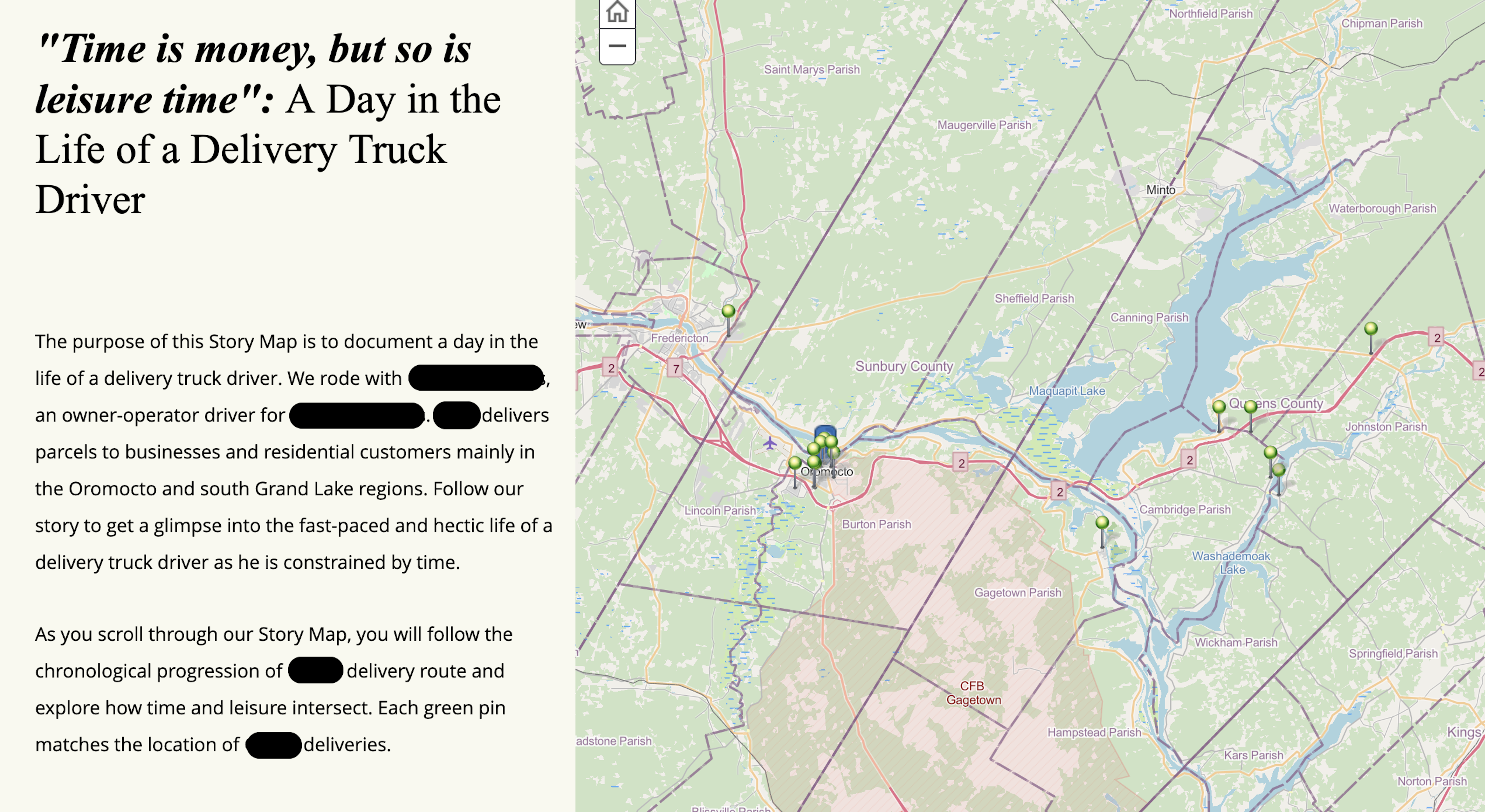

Allen and his collaborator chose to document the working day of a delivery truck driver in the Fredericton and Oromocto, New Brunswick region. For the sake of anonymity, the driver and his company will not be named. We include below excerpts from the assignment that followed a delivery truck driver through a day’s work.

FIGURE

1. Overview of Story Map

The purpose of this Story Map is to document a day in the life of a delivery truck driver. We rode with Bob, an owner-operator driver for ACME Delivery1. Bob delivers parcels to businesses and residential customers mainly in the Oromocto and South Grand Lake regions. Follow our story to get a glimpse into the fast-paced and hectic life of a delivery truck driver as he is constrained by time. As you scroll through our Story Map, you will follow the chronological progression of Bob’s delivery route and explore how time and leisure intersect. Each green pin matches the location of Bob’s deliveries.

The delivery truck driver starts his day at a cargo and sorting depot on Fredericton’s Northside at 5:45 am. The driver is not paid for the 1 to 1.5 hours it takes him to collect, verify, and sort his deliveries into sequential order, which will in turn save him time. The driver explained to use that he is only paid during the time that he is making deliveries. He is compensated for the number of packages delivered which is also factored by the distance he needs to drive to make the delivery. Therefore, in his work, time is money. He is also not paid for taking breaks, lunch, or stops along the way that are not delivery related. The conception of free time versus unpaid labour was a recurring theme in our ride with Bob. Since the worker is not paid for lunches or breaks, he is forced to work swiftly and accurately, so as to not waste time. The result is often distracted driving, where he is forced to eat while driving or to check his parcel scanning device while on-the-go.

Trust. ACME drivers are trusted with delivering sensitive, private, and secure packages. Bob said he regularly delivers up to $250,000 worth of pharmaceutical drugs each day. Company drivers are bonded and must pass a criminal record check before employment.

Wasting Time. If Bob does not load and organize his truck properly, and if a logical route is not planned ahead of time, Bob risks “wasting time.” Bob packs the back of his truck so that he can grab home deliveries from his cab, and larger packages from the rear cargo door. All boxes rotate clockwise so that they are in order. He reorganizes his cargo around his noon lunch break at Sobeys in Oromocto. After leaving Base Gagetown, Bob stops next to deliver parcels to Oromocto’s main grocery store and drugs to the pharmacy:

Pharmacy / Privacy. Bob is trusted to deliver expensive pharmaceuticals (narcotics, opioids, etc.). Pharmacists trust that Bob will deliver the pharmaceuticals on time, as well as adhere to their customers’ privacy.

Goodfood Delivery. Goodfood and HelloFresh parcels / boxes are delivered each Wednesday and Friday, making for larger loads and more stops in residential areas (most are in Oromocto). These deliveries are quick, as he does not need to ring the doorbell — packages like these can be left at the front door. Bob takes a photo of the delivery, which helps account for the delivery in case of lost packages.

Post-Modern "Good foods"? Bob delivers Goodfood and Hello Fresh food preparation parcels, which he has seen a steady rise in delivery. Bob expressed his skepticism about why people feel they need / want boxes of kit food delivered to their homes. He was aware of the massive promotion of such products, and how there is an erosion of valued time for meal preparation with families.

Drop & Go! Bob doesn’t mind residential stops, as he can leave parcels at the front door: no “wasted time” waiting for someone to answer the door. He takes a photo on the ACME wireless device as proof.

Checking ACME Wireless Device. Bob uses a Panasonic wireless device that scans and uploads / downloads parcel information, as well as takes photos of parcels delivered.

“It's Only Wrong If You Get Caught”. The pressure that Bob faces in the run of a day is apparent in this photo. Bob feels the need to basically text and drive — Loomis sends updates and alerts several times a day, which are time-sensitive. Bob is aware of the risk of illegal texting and driving and stated that he has to watch out for police.

Residential Deliveries. Most of Bob’s residential deliveries were Goodfood packages or Walmart parcels. His residential deliveries depend on the contracts that ACME has with big business.

“Walmart Shit”. Bob calls these packages “Walmart Shit”, as he is incredulous of all the Walmart products / parcels that he delivers. Some people order Walmart food and Walmart goods all the time, which raises questions about profitability of delivery costs and carbon footprint. However, Walmart does offer free shipping, which helps for those who cannot drive to Walmart (this raises other questions about the need for people to have cars).

Liminal Spaces. Behind most commercial businesses are delivery areas which the public rarely see. Bob’s big-business / commercial delivery stops are spent mostly in liminal spaces — the areas behind buildings and businesses which the public seldom see. These areas are dirty, dusty, and rusty.

FIGURE

2. Bob delivering a firearm to a

Canadian Tire store

Lunch at Sobeys Parking Lot. Gary usually stops for lunch (time-permitting) around the time he done delivering at Canadian Tire and/or Sobeys (he says this is usually between 10:30-11:00). If he’s ahead of time / schedule, he tries to squeeze in a 5k-10k run on the trails in Oromocto; if he’s short on time, he eats while driving.

Pressed for time. Bob is not paid for lunches or breaks, so he needs to make his own time by either working fast to get ahead of the clock to allow for breaks or leisure, or risks making the day longer for himself. This forces Bob to multitask (while driving), which can include eating on-the-go. He usually condenses his morning so that he has time to spare in the afternoons to go the gym (if he doesn’t get a chance to run in the mornings). He changes between running gear in the back of his truck.

Rural Delivery. For the first stop past Oromocto after lunch, Gary stops in the Village of Gagetown to make a delivery (Goodfood). After taking the Trans-Canada highway out of Oromocto, Bob leaves the highway to deliver one parcel of Goodfood to a household.

FIGURE

3. Bob delivering one of many Goodfood

parcels

Carbon footprint. Think of the carbon footprint that one box of Goodfood costs the planet. Bob reached highway speeds and cruised at the most efficient speed possible for about 15 minutes before leaving the highway at the Village of Gagetown exit. He then drove for about 20 minutes to make the delivery, then back to the highway. All that driving and burned hydrocarbons for just one parcel: there's no such thing as “free shipping” when it comes to the planet.

FIGURE

4. Looking back into Bob’s truck

Convenience Store Delivery. Bob is always concerned that the owner of a convenience store will be around when he makes deliveries. Bob has been shouted at for parking his truck near the store, as the owner says that he will block customers. The store has the monopoly on convenience products and gas in the town, as it is the only store in a considerable radius. There is a loading / freight area, but Bob cannot use it, as it’s full of junk. Instead, I helped Bob deliver packages into the crowded convenience store.

Handle with Care. Bob is tasked with delivering valuable and time-sensitive parcels to pharmacies, but I did not expect that he would have to deliver sensitive cryotoxic packages. Small town businesses, like pharmacies, rely on delivery truck drivers’ promptness for their products. Bob is conscious of time, as well as the expectations his customers and the company have of him.

Nursing Home Delivery. The nursing home residents love it when Bob stops by. Bob describes how he has been a regular (and punctual) visitor, getting to know some of the nursing home residents; he said that “it makes his day” when some of the elderly residents greet him.

The Final Destination (Not a Pun). After joking that the Nursing Home was in the middle of nowhere, Bob points out that the nursing home is new and of (seemingly) acceptable standards. The nursing home, like the pharmacies, rely on Bob being prompt when delivering pharmaceuticals. In many ways, Bob is bound by time. I asked if this was Bob’s final stop. He didn’t get my morbid pun and told me that we were headed to our last stop of the day in Coles Island — another 25km east on the Trans-Canada.

Irving Small Package Delivery. The final stop before heading back towards Fredericton. Bob delivers one parcel to the Irving station near Coles Island, his maximal distance stop.

Time is money. Fuel expense is paid by ACME drivers (owner-operators). The longer it takes to drive somewhere and to deliver, the longer the driver’s day is. They are paid by packages delivered and kilometers driven. Despite the financial gain of having further deliveries, the cost is time.

DISCUSSION

Theoretical notions of time

The notion of free time, saving and wasting time, as well as being pressed for time, were recurring themes in the driver’s day and in the nature of work. Foucault (1975/1995) outlines the use of timetables as a form of discipline on human activity and work — timetables inherited from monastic communities, Protestant militaries, and the Industrial Revolution. The ensuing adoption of time as a form of control upon workers realized an extension of the wage-earning class partitioning of time on nearly all facets of life. Foucault mentions that the detailed partitioning of time, quality of time, and useful time are forms of discipline and control on “docile bodies” (p. 150). “Time measured and paid must also be a time without impurities or defects; a time of good quality, throughout which the body is constantly applied to its exercise” (Foucault, p. 151). We witnessed the continuation of wage-earning partitioning of time when riding with the delivery driver; the time working, resting, eating, etc. was inexorably and creatively linked with the underpinnings of modern capitalism.

Weber opposed the Marxist concept of dialectical materialism and traces the rise of capitalism to the Protestant work ethic. In Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism, Weber (1905/2002) contends that the development of the “capitalist spirit” (e.g., work ethic) with development of rationalism as an ethos, “labor in the service of a rational structuring of the provision of the material needs of humanity has always been one of the guiding purposes of [the Protestants’] life’s work” (Weber, 2002, p. 26). Weber utilizes the lifestyle of Benjamin Franklin as to make an example of an overly righteous lifestyle and philosophical model that contradicts more recent economic models, where higher wages incentivize workers to work harder and more efficiently (Solow, 1979; Akerlof, 2002). The Protestant / Calvinist / puritan asceticism towards “work as the end and purpose of life commanded by God” (Weber, p. 107). is exemplified in the reflections / maxims in Franklin’s famous autobiography: where he espouses “time is money”, where “wasting time” is one of the most serious of all sins, and where “work hard in your calling” equals fruitful labour and meaningful life (Weber, p. 106–107). Franklin is used as a metaphor to represent the Protestant ethic and ethos of modern capitalism: that the explicit moral attitudes towards economic activity and work, the rationalized approach to living, and the ascetic of Protestantism are what led to the formation of the “capitalist spirit” and economically rational conduct of life (p. 27).

Discursus in political theory

The resounding observation of the delivery truck driver was his relationship between his work, time, and fastidiousness of his actions contrasted by what he was doing, i.e., delivering commercial goods to consumers. The power of profit is strong; profit is the driving force of capitalism (Shaikh, 2004). Thanks to the myth that the accumulation of goods makes one happy, consumers propel the capitalist system of goods and services. The delivery truck driver is merely a cog in a much larger system of free market capitalism. Marcuse (1991), writing in the aftermath of Totalitarian regimes and the Holocaust, theorizes that the freedom of enterprise is not a blessing, but a symptom of the technological processes of mechanization and standardization that has released “individual energy into a yet uncharted freedom beyond necessity” and that “advanced industrial civilization imposes its economic and political requirements for defense and expansion on labor time and free time, on the material and intellectual culture” (p. 2–3). Marcuse’s indictment of modern industrial capitalism is a grim warning of the underpinnings of technology and consumerism as extensions of what contributes to the waning of critical and reflective thought — the resulting “one-dimensional” human outlook on life. Similarly, Horkheimer and Adorno of the Frankfurt School of thought, point out that the “coercive nature of society alienated from itself” is the symptom of technological rationales of the post-war “culture industry” (Horkheimer & Adorno, 2002, p. 121). The dual achievements of standardization and mass production have been achieved at the cost of the logic of work and social systems. The resulting culture monopolies are the objective social tendencies is the hidden subjective purposes of the most powerful sectors of industry: steel, petroleum, electricity, and chemicals (p. 122).

Today we see the pervasive power of petrocapitalism, transnational corporations, and a rise in fascist, populist, governments as part of an inescapable process of hubris — where humans increase their power over things of this world, which, in turn, furthers and perpetuates world alienation (Arendt, 1958/1998, p. 252). Arendt spent much time exploring the results of world alienation over self-alienation, which she describes as the “hallmark of the modern age” (p. 254). We have witnessed the results of the “banality of evil” personified by the “rational man / cog in a machine” bureaucratic actions of Adolf Eichmann during the Holocaust. Eichmann, as portrayed by Arendt’s coverage of his trial in Jerusalem, was “neither perverted nor sadistic” as a Nazi war criminal, but “terrifyingly normal” (Arendt, 1963/1994, p. 276). Eichmann is the exemplar of the rational person — the bureaucratic cog — who took great pride in his work to the detriment of others. As witnessed throughout the modern age, we encounter the exploitation of marginalized people, expropriation of workers’ labour, and obscene accumulation of wealth in the vast minority of the population. Cynically, we have been discussing the way that as educators of pre-service teachers (Casey) and of young people in school systems (Allen), we are working to strengthen the status quo by educating future workers. Optimistically, we think that engaging in creative pedagogies can help to enlighten students to the reality of our shared experience; we orient ourselves towards the knowledge of our experience, as well as developing critical consciousness for its own sake. But is criticality enough, even when harnessed through creative pedagogies? On this point, Casey (hardening cynic) and Allen (critical optimist) are split.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS AND LINGERING QUESTIONS

As we look back on Allen and his collaborator’s engagement with the work and leisure assignment, we see the potential for the assignment to encourage pre-service teachers to creatively engage with social critique and action. In reflecting deeply on the assignment, Casey wondered, what might this examination of work and leisure minimize? We were engaging in work on unceded Wolastoqiyik territory, though intersections of colonialism, land theft and dispossession did not come through explicitly in the pre-service teacher assignments. This left Casey wondering: how might a future iteration of this assignment focus more directly on interrupting settler colonialism, and the intersections of colonialism, land theft and dispossession?

Casey also notes that not all pre-service teachers were comfortable engaging deeply, creatively or critically in this assignment. Some groups, those not invited to continue to think and write about their assignments and experiences, merely fulfilled the assignment guidelines (follow and document a worker’s journey) without applying any analysis to this work. Casey sees a danger in this kind of creativity — engaging creatively in a ‘fun’ assignment without applying a political analysis, without thinking deeply about structural racism and space, without engaging with ideas of schools and subjects (Geography, Social Studies) as static, apolitical constructions. This tendency to want to deliver a neutral curriculum neutrally is, of course, impossible, but this desire for neutrality remains a dominant assumption about what teachers should and should not do.

Despite the example of some of the pre-service teachers’ apolitical creative works, we still see the opportunity in encouraging pre-service teachers to examine their positions, agency, and social value (Wiebe & Smith, 2016) both within and beyond classrooms through this kind of inquiry. Casey has been grappling with the balance between creative pedagogies and her role as a teacher educator. Throughout the course, she mentioned that she was wresting with the notion of educating pre-service teachers who were destined into the workforce, who would then replicate the status-quo. The assignment was designed to foster intrinsic learning about the intersections of work and time, of the political nature of movement and space, and to politicize the nature of assessments within the Geography classroom by encouraging learners to think deeply about agency and social value. What does it mean that many of the learners in the classroom were resistant to this kind of overt politicization? What does it mean that Allen was receptive to the idea and so continued to think through these ideas through this written collaboration?

Through our collaboration, by looking back on an assignment to map work in New Brunswick, we have argued that Geography must be taught with an explicit political orientation to disrupt the notion that place and space are apolitical concepts. We sought to center the ways that dispossession, migration, disruption, and control of space and place highlights the ways that whiteness and settler colonialism seep into Geography curricula in the context of New Brunswick. A politically and creatively oriented Geography classroom offers space address some of the most pressing concerns facing us collectively—climate change, racism, anti-Indigeneity, gender-based violence, among others. This version of Geography teaching presents learners with opportunities to research and unsettle the status quo, to notice the things we often take for granted—including the ways that work operates within our local contexts and seeks to center the communities who have been historically dispossessed. This kind of creative Geography teaching even offers the potential to disrupt anthropocentric worldviews (Davis & Todd, 2017). To suggest that there is one way of experiencing space, centers settler colonial ideals about place, naming, and disregards the myriad ways that especially Indigenous and Black folks experience discrimination across spaces and structures. A nuanced and political Geography curriculum must engage creatively, yes, but more importantly, it must focus on the ways in which space, place and location are experienced relationally and are open in different ways to different kinds of people.

NOTES

We have provided a pseudonym for the driver and his company to protect his anonymity.

References

Adjei, P. B. (2018). The (em)bodiment of blackness in a visceral anti-black racism and ableism context. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(3), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.1248821

Alcoff, L. (2009). The problem of speaking for others. In A. Jackson and L. Mazzei (Eds.), Voice in qualitative inquiry: Challenging conventional, interpretive, and critical conceptions in qualitative research (pp. 117–136). Routledge.

Adorno, T. (1998). Critical models: Interventions and catchwords. Columbia University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/ador13504

Akerlof, G. A. Behavioral macroeconomics and macroeconomic behavior. American Economic Review, 92(3), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1257/00028280260136192

Arendt, H. (1994). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the banality of evil. Penguin. (Original work published 1963)

Arendt, H. (1998). The human condition. University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1958)

Buckingham, D. (2009). ‘Creative’ visual methods in media research: Possibilities, problems and proposals. Media, Culture, and Society, 31(4), 633–652. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443709335280

Buckingham, D., & Willett, R. (2013). Digital generations: Children, young people, and the new media. Routledge.

Mustafa, N. (Executive Producer). (2019, June 14). Reclaiming Marxism in an age of meaningless work [Audio podcast episode]. Ideas. CBC Radio. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/reclaiming-marxism-in-an-age-of-meaningless-work-1.5175707

Choudry, A., & Kapoor, D. (2010). Learning from the ground up: Global perspectives on social movements and knowledge production. Palgrave MacMillan.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of discrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist practice. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Davis, H., & Todd, Z. (2017). On the importance of a date, or decolonizing the Anthropocene. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 16(4), 761–780.

de Lange, N. (2012) Researching to make a difference: Possibilities for social science research in the age of AIDS. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 9(supp 1), S3-S10. https://doi.org/10.1080/17290376.2012.744897

Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline & punish: The birth of the modern prison. Vintage. (Original work published 1975)

Fox, M., Mediratta, K., Ruglis, J., Stoudt, B., Shah, S., & Fine, M. (2010). Critical youth engagement: Participatory action research and organizing. In L.R. Sherrod, J. Torney-Puta & C.A. Flanagan (Eds.), Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth (pp. 621–649). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470767603.ch23

Freire, P. (2013). Education for critical consciousness. Bloomsbury.

Freire, P. (2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed: 50th anniversary edition. Bloomsbury.

Gordon, P. J. (2011). Building voice, taking action: Experiences of youth from a civic focused school. (Publication No. 3486002) [Doctoral Thesis, Harvard University]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://www.proquest.com/docview/909002130

Giroux, H. A. (2017). On critical pedagogy. Bloomsbury.

Horkheimer, M. & Adorno, T. W. (2002). Dialectic of Enlightenment. Continuum.

Illich, I. (1971). Deschooling society. Marion Boyars.

Kishori, N. (2009). Transforming multiple hierarchies: Polyvocality, flux and problems of identity in multicultural women's writing. The IUP Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 1(1), 46–60.

Kyle, K. (2019, July 30). Arctic wildfires breaking records, in numbers and emissions. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/arctic-wildfires-1.5228945

Lewis, S., & Maslin, M. (2015). Defining the Anthropocene. Nature, 519, 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14258

MacEntee, K., Burkholder, C., & Schwab-Cartas, J. (2019). Cellphilms in public scholarships. In P. Leavy (Ed.) The Oxford handbook of methods for public scholarship, (pp. 419–442). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190274481.013.13

MacEntee, K., Burkholder, C., & Schwab-Cartas, J. (2016). What’s a cellphilm? Introducing the methodology. In K. MacEntee, C. Burkholder, & J. Schwab-Cartas (Eds.). What’s a cellphilm? Integrating mobile phone technology into participatory visual research and activism, (pp. 1–15). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-573-9_1

Marcuse, H. (1991). One-dimensional man. Beacon Press.

Marshall, T.H. (1977). Class, citizenship and social development. University of Chicago Press.

Maynard, R. (2017). Policing Black lives: State violence in Canada from slavery to the present. Fernwood Publishing.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1978). The economic and philosophic manuscripts of 1844. In R. C. Tucker (Ed.), The Marx-Engels reader (2nd ed.). (pp. 66-125). Norton.

Nixon, R. (2011). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Harvard University Press.

O’Donnell, S. (June 1, 2019). Speaking up for reproductive rights and access to abortion in New Brunswick. NB Media Co-op. http://nbmediacoop.org/2019/06/01/speaking-up-for-reproductive-rights-and-access-to-abortion-in-new-brunswick/

Pithouse-Morgan, K., Muthukrishna, N., Pillay, D., Van Laren, L., Chisanga, T., Meyiwa,T., Moletsane, R., Naicker, I., Singh, L., & Stuart, J. (2015). Learning about co-flexivity in a transdisciplinary self-study research supervision community. In K. Pithouse-Morgan & A. Samaras (Eds.), Polyvocal professional learning through self study research, (pp. 145–171). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-220-2_9

Pithouse-Morgan, K., Inbanathan N., & Pillay, D. (2017). “Knowing what it is like”: Dialoguing with multiculturalism and equity through collective poetic autoethnographic inquiry. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 19(1), 125–143. http://dx.doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v19i1.1255

Rogers, M. (2017). Participatory filmmaking pedagogies in schools: Tensions between critical representation and perpetuating gendered and heterosexist discourses. Visual Research and Social Justice, 11(2), 195–220. https://doi.org/10.26522/ssj.v11i2.1522

Schratz, M., & Walker, R. (1995). Research as social change: New possibilities for qualitative research. Routledge.

Shaikh, A. (2004). The power of profit. Social Research, 71(2), 371–382. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40971701

Solow, R. M. (1979). Another possible source of wage stickiness. Journal of Macroeconomics, 1(1), 79–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/0164-0704(79)90022-3

Sultana, F. (2007). Reflexivity, positionality and participatory ethics: Negotiating fieldwork dilemmas in international research. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 6(3), 374–385. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/786

Turner, B. S. (1990). Outline of a theory of citizenship. Sociology, 24(2), 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038590024002002

Weber, M. (2002). The Protestant ethic and the “spirit” of capitalism and other writings (P.Baehr & G. C. Wells, Trans). Penguin. (Original work published 1905)

Wiebe, S., & Smith, C. C. (2016). A/r/tography and teacher education in the 21st Century. McGill Journal of Education, 51(3), 1163–1178. https://doi.org/10.7202/1039633ar