FIGURE 1: Poetic Outlining Example

(Un)seen undulation: Reflecting on the ripples made by artist-teachers and researchers

ADAM VINCENT University of British Columbia, University of the Fraser Valley

When I meet new people, I am often asked the usual question of “What is it that you do?” The open-ended question leads my brain down a multitude of pathways, and I try to follow all of them until they intersect or bisect at a point where my words can begin. I often say, “I am an instructor, a teacher”. They nod. I then add, “But I am a poet, a writer, a researcher.” Brows furrow. “I am a poet, teacher, artist, educator…” I stop myself. They ask, “What do you teach?” “I teach in the areas of education and communications.” They get it. I muddy the waters. Thinking of my research, I then harken back to my initial readings of Prendergast (2009) and Leggo (2005) and the now dozens of others whose work converses with my own, I speak again: “But I also include elements of poetry and poetic inquiry to support students in thinking outside of the proverbial box. I challenge them to consider how they can think and learn in different ways. This helps them to identify ways to personalize their learning, giving their learning greater purpose, which ultimately keeps them motivated as they navigate their educations. What I mean to say is that I support students in using poetry and art to learn more than I think conventional means can teach them, but then I always bring them back to conventional forms and norms so that they understand how to be within the system.” Smiling and nodding, an unabashed shift to a discussion about the weather. I have come to realize that I need to work on how to express what I do (in my role as an educator, scholar, and poet) so that people ‘get it’ and so that I can have fewer conversations about the weather.

These are typical interactions in some social settings. This is a recurring issue when it comes to describing what I do. These occurrences now see me considering how our work as creative pedagogues contributes to our students’ lives and beyond. In this article I address such questions as: What is a creative pedagogue? Who am I in relation to that title? What do I do that some of my colleagues do not do? My conversation, finding my way to an answer, is not conventional, I choose instead to lace my thoughts with poetry. I begin by looking at how I integrate poetry into my two major roles, one as a classroom instructor in two major universities in Western Canada, and the other as a Learning Strategist, who works in academic support in one of the aforementioned institutions. I then move from the pragmatic nature of what I do, written in prose, to an exploration of self and the impact of what I do through the medium of poetry. Having previously felt adrift in the academy, I have chosen to enact, through this poetic exchange, a conversation with my late mentor whose many decades of teaching and writing provided a home for my own work. Through a mixture of prose and poetry, I seek to better identify what it is that I do, why I do it and what ripples my approach to educating may cause (both seen, like that of water, and unseen, like that of a breath of air) for my students and beyond.

Creating Poetry: Informing Teaching, Informing Curriculum

The poetry in my research seeks to better understand my positionality, to see the unseen (like the wind gently creating ripples on the water) and to expand on my understanding of lived experience, contradictorily enough, by using shorter lines and poetic devices to encapsulate grander experiences. This is the same in my teaching. I strive to facilitate a greater understanding in my students by giving them the permission that they seem to need to explore differently. I exemplify and promote ways to use language differently in order to find deeper meaning. Is that what a creative pedagogue does? Do we give permission that some need, simply by living our craft? Do we use our position to show our students that you can at once adhere to convention while being unconventional as you learn and grow?

I have spent the last decade engaging with learners on the post-secondary level. From work as staff and faculty in university academic support centres to lecturing, facilitating, and teaching in the classroom in a number of major Western Canadian universities. I have dedicated much of my life to helping others through their higher education journeys. During this time, I have created ripples. I have integrated my passion for poetry and arts-based approaches to research, learning and teaching into my own teaching practice. Over the years, I have also presented on the topic at a number of conferences and facilitated workshops for other faculty members who wish to reach students who they see as unreachable. I promote multimodality and creating lessons using the tenets of universal design for learning (UDL), based on the work of Story, Mueller, and Mace (1998) and the contemporary work being done by CAST (2018), and encourage faculty members to adhere to the fundamental concepts associated with appreciative inquiry, based on the work of Cooperrider and Whitney (2005). I then create ripples as I promote and exemplify the use of poetry across the disciplines as a tool for deeper learning; that is learning that extends beyond rote memory and ventures into layers of understanding and application that is ultimately more personal for the student This use of poetry as part of my teaching practice began during my time in our academic support centre (The Learning Centre) where students would request help with writing their introductory English essays, the 5X5 expository essays (five paragraphs, five sentences) that nearly all students are required to do. It is here that I first saw the anxiety that students had over the form of the standard academic essay and I wanted to find a way to break away from the form and focus on the ideas. This would not only help students with one particular assignment, but it would also show them ways in which arts-based approaches could allow their thoughts to develop before having to write for course required conventions.

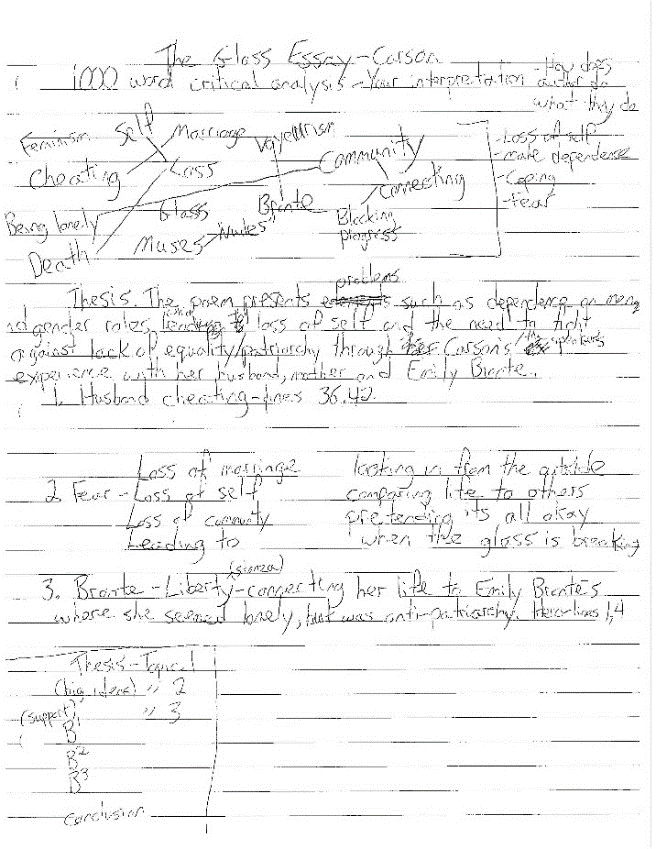

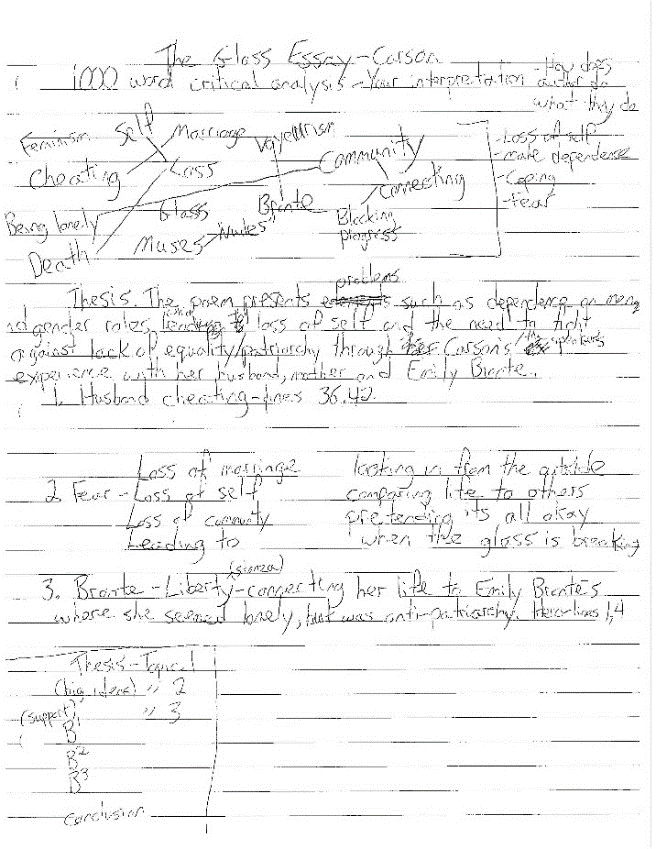

To begin, I took the learning strategies of mind-mapping and concept mapping and thoughtfully integrated my knowledge of poetry and poetic forms. I asked students to write short lines of ideas (not complete or complex sentences), use metaphors or similes (asking them such questions as “If you could describe your idea using different words, what would you say? What is it like?” “Is there something concrete that you would say X is like?”). I would then have them cluster their ideas into common themes, akin to that of a poetic stanza, and then worked with the students to take this free verse poem and transpose it into an essay outline and then finally their essays (see Figure 1). I am aware that in creating ripples that I must ensure that they do not turn into damaging waves; they must help to propel the students along in their academic journeys. Students were able to get their ideas down on the page, often using non-academic language or metaphors to express their thoughts and understandings, and position their ideas in a conventional essay outline template. This allowed them to see that they had strong ideas, arguments and evidence that could meet their assignment criteria, but that they had to process their knowledge differently before using academic language, conventions, and forms.

FIGURE

1:

Poetic

Outlining Example

This rippling idea of breaking away from requested forms and using metaphors and descriptive language proved itself useful for students in such areas as biology and chemistry, as they tried to identify parts of the body, parts of cells, biological events, and chemistry problems. Seeing the problem differently resonated with them deeply and I was able to support them as they brought their ideas and knowledge forward into the requested format(s) of their instructors. Lab report details became clearer as they understood the processes that occurred in a more meaningful way. Word counts for their papers also became less of a concern as their initial arts-based interactions with course concepts, then synthesized critically with the literature, provided students with greater depth and breadth to write on.

I continued to integrate poetry, especially lyrical poetry, into my classroom teaching practice. In my courses which focus on university transitions, educational theory, critical reflection and basic communication skills, poetry has provided an additional layer to my curriculum. For example, I have used music and poetry to link to larger concepts and themes (e.g., using such songs as Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall” to discuss models of schools), to show students that learning exists beyond the classroom (promoting intertextuality) and to offer poetry as an acceptable form of reflection. This different way of reflecting has allowed them to better know who they are as individuals and what they would like to get out of their education. This moving away from and beyond the standard response paragraphs has provided a formative and summative way for students to demonstrate their engagement with course concepts. Receiving positive responses from students, as they are related to their non-standard reflective practices, then lead to me integrating poetry itself or elements of poetry (e.g., using poetic devices such as metaphor or rhyme and various textual forms to engage students differently) into my lessons. Instead of having small group discussions about concepts with strict prompts, I created a ripple where students were asked to use metaphors to show the depth of their understanding and to support their classmates in thinking beyond their expectations of what learning is or looks like. This yielded deeper meaning-making opportunities and saw a greater level of criticality for most students as they linked their metaphor not only to course concepts, but what that concept meant in their lives. This formative assessment technique, which I sometimes refer to as poetic triangulation (using course content, personal reflection, and poetic devices), also led to greater classroom engagement. Through the vulnerability of sharing their metaphors and what they mean to them, students built stronger bonds and mutual respect.

As I design with creativity, married with theories of curriculum development; as I facilitate knowledge creation and collaboration through words, both academic and non-academic; and as I support crafting and craft development through modeling and directive techniques with metaphors to further understanding, I sometimes wonder where I fit within the academy.

Rippling Realizations of the Poet-Teacher

Leggo (2012) wrote:

“As a poet, I often wonder

if anybody besides other poets

really care

about poetry.

And as an educator,

I often worry

about the influence of schools,

curricula,

and teachers

in shaping the literacy experiences of learners.

And as a language and literacy researcher

with a focus on poetic inquiry,

I often wander in the magical places of the alphabet,

with a wand in hand,

ready to spell possibilities

for new ways of seeing and knowing” (p. 143)

Ultimately, Leggo asked: what is a poem good for? (p. 141)

Had he still been here

not an infinite number of time zones away

reposing with rhetoric

from a life lived poetically (Leggo, 2005)

with successful semantics

resonating in hearts and minds

brought forward from

his life of love

for and with language

for and with teaching

for and with family

I would have asked him

‘Carl (for I knew him with kindred spirited familiarity, over coffee and nicoise),

what is a poet good for?’

We would then talk for hours

about poets

and poetry

and promoting pops of inspiration

and introspection

to create a world where students feel

liberated

to learn, to explore

to be.

Yet, I have to ask myself:

do I pop inspiringly?

I position myself as a poet

as an educator

(facilitator, demonstrator, creator, investigator of ideas)

who pushes poetry

(peacefully)

in to view,

(unavoidable unless you swerve or swivel daftly and intentionally

or squint so tightly that the light cannot get in),

in hopes of inspiring change

with(in) each student

that may ripple through society

building their creativity and capacity

to learn differently

to seek their own way to contribute

to their micro or macrocosm.

I wonder:

What, then, am I?

Does this make me an a/r/tographer? (Irwin, 2013)

I am

Poetic a/artist/

choosing words as my instrument of expression

metaphors merging meaning

spoken or spiraled in scrawl

(admittedly) only I can read.

I am a r/researcher/

I research that which came before

delving into the literature

picking the minds of mentors and colleagues alike

to push myself to do more

to give the facts for those who ask

to present the path blazed by others:

their successes

their follies

their foibles

their lessons for me to apply

to my crafting of curriculum

to my creation of crisp mind calligraphy

imagery of stanza upon stanza

of symphonic language

of sequenced cadence

composed with the intent to teach aesthetically

supported by the giants

whose broad shoulders I stand upon

offering my hand for others to stand next to me.

I am t/teacher/ by a variety of names

too many to count.

Fashioning fora for forays into fundamentals

bolstering and buoying forethoughts for success

stretching myself beyond institutionally given titles

which ask me to question myself

What am I good for?

What is a poet, researcher, teacher good for?

I/we inspire

through a modelled life

a mere suggestion of a way of being

living artistically

poetically

phonetically sounding out the inspiration inside

so that it is heard, clearly

with the hope of rousing rippling realizations

of what education can do

of what art can do

of what the marriage of both can do

for each individual student

for each community

for each strand of humanity in this world.

I/we practice our preaching

by not only teaching our craft

but integrating it into our praxis

to demonstrate how to use creativity economically

in ways that support and stimulate

not dominate

not the cliché of artistic anarchy

where only the art, not purpose, matters

Our craft is our conviction

our conviction is our craft

To contribute to the enlightenment of humanity

through aesthetic thoughtful artistry of knowledge

I think I see it now.

I think I know, Carl.

I know what we are good for.

I know what I am good for.

Still watching the ripples

As in my poem, I recently stopped questioning my value as an educator and embraced my identity as an artist-teacher with an affinity for arts-based research. This is due in large part to seeing the impact of my work (the ripples) on students and their academic journeys. I have had the honour of having some students openly express their enjoyment of my courses and share their new or different realizations that coincided with our classroom discussions (other factors in their lives also seemed to sync at once). This, as other educators can likely relate, is one type of exchange that propels us forward in our academic and teaching endeavours. For my students, these changes are as small as approaching their course readings differently or as significant as changing their ultimate educational goals and career paths. I have also had students return after their consultation in The Learning Centre, where I support students as a Learning Strategist, to share how adapting their approaches to learning led to greater academic success. I am aware that these changes did not happen in a vacuum and that students are constantly adapting and changing, but I cannot help but believe that expanding their awareness of different ways to learn and arts-based approaches to learning caused a spark in them. This small realization that learning need not be constrained gives students the means to personalize their learning, while not forgetting the necessity of communicating through conventions. They develop the power to communicate in and through multiple forms of expression which better demonstrates their understanding and causes deeper learning to occur. Through my crafting of poetry and curricula, designed to use academic research (e.g., the tenets of UDL) and art (from use of form, metaphor, line breaks and enjambment) to draw students in and expand their views on learning, I have found my own way to support students and ultimately support how they live in the world. Some students fully embrace the notion of using art in their daily lives as a means of expression, as a way to learn and as a way to think differently, while others resist these ideas. Whether or not a student has been consciously changed is no longer an issue for me in my practice. I believe that offering an awareness that extends beyond their usual confines of thinking, an action that creates a ripple, is enough. Creative pedagogues, artist-teachers, a/r/tographers, poetic inquirers, narrative inquirers, arts-based researchers, people who teach and create art, whatever their title may be, are working in current educational systems to give students further opportunities to learn and to be in the world and to create their own ripples.

To me, that is poetry.

References

CAST (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Cooperrider, D. L., & Whitney, D. (2005). Appreciative inquiry: A positive revolution in change (1st ed.). Berrett-Koehler.

Irwin, R. L. (2013). Becoming a/r/tography. Studies in Art Education, 54(3), 198–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2013.11518894

Leggo, C. (2005). Pedagogy of the heart: Ruminations on living poetically. The Journal of Educational Thought (JET) / Revue De La Pensée Éducative, 39(2), 175–195.

Leggo, C. (2012). Living language: What is a poem good for? Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies, 10(2), 141–160.

Prendergast, M. (2009). “Poem is what?” Poetic inquiry in qualitative social science research. International Review of Qualitative Research, 1(4), 541–568.

Story, M. F., Mueller, J. L., & Mace, R. L. (1998). The universal design file: Designing for people of all ages and abilities. Center for Universal Design, NC State University. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED460554