Transforming Graduate Studies Through Decolonization: Sharing the learning journey of a specialized cohort

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) affirmed that education is an important pathway towards reconciliation, through an increased emphasis on acknowledging Indigenous people, languages, and land, and building inter-cultural understanding, empathy, and mutual respect. Recommendation #10 in the Calls to Action of the TRC’s report specifically relates to decolonizing teacher education and developing transformative pedagogies (TRC, 2015, p. 2). Our graduate program aligns with these goals as we have developed a specialized cohort that explicitly focuses on decolonizing education. Through our research, we have found that educators need support and a caring community to unlearn the legacy of the colonial education most of us have received. Decolonizing education includes (re)examining historical narratives, confronting the attempted genocide of First Nations, Métis and Inuit (FNMI) peoples, understanding the legacy of residential schools, and the continuation of the separation of Indigenous parents and children through the auspices of child welfare systems, challenging negative myths and stereotypes about Indigenous peoples, as well as learning, sharing, and valuing knowledge with and about Indigenous peoples. We recognize that the work of decolonization is an ongoing process. In order to better understand our own decolonizing practices and the impact of our program, we are embarking on an ongoing multi-year, multi-group study. Here we share our learning journey with and alongside the first group of educators in the Indigenous-focused cohort (2014-2016), who nourished their own learning spirits as they learned about affirming the learning spirits of others, and deepened their understandings and agency in their efforts to decolonize their curricula, practices, and work at transforming and changing all levels of the educational system.

Context

Education has been said to be an emancipatory tool that can change the world. However, if we listen to the voices of Indigenous people, we need to be mindful that the type of education that is provided is important. From this perspective, the educational institution may not only be seen as a positive force, but a negative force; the history of residential schools in Canada unequivocally shows that education may be hurtful and damaging to Indigenous youth, their families, and communities (Knockwood, 2001; Milloy, 2006; TRC, 2015).

Marie Battiste (2013) shares her memories of the colonial education she received:

I remember little about my Eurocentric education or the conventional approaches that I had been part of. I tried to stay under the radar of the teacher, not to be noticed or labeled dumb. Little is there I care to remember. Many memories I have long ago let go. But what I think is important is my own path toward understanding the collective struggles of Indigenous peoples framed within a patriarchal, bureaucratic enterprise of government, with education used as the manipulative agent of various intended outcomes, some well-intentioned, some not, but all strategic. These collective struggles are the transforming points of my learning and vectors from which I grew into new responsibilities. (p. 17)

In acknowledging the school system’s destructive assimilation project that often limits and fails to affirm Indigenous children and their community’s knowledge systems, Battiste finds a strength from which to be responsive and responsible and imagine education anew. Colonialism has systemically eroded and devalued Indigenous people, languages, and land (Kovach 2009; Loomba, 2008; Smith 1999). This legacy of cultural genocide was further reinscribed through the residential school system (TRC, 2015) and child social services (Blackstock, 2012). Transformation of the colonial system through decolonization operates in two ways (Battiste, 2013): First, reactively — by challenging the negative overt and covert beliefs and practices surrounding Indigenous people, and rejecting the discrimination the colonial project institutionalizes through education and other governmental systems (Battiste, 2013); and secondly, proactively — by constructing a positive narrative of Indigenous people, their knowledge systems, and their value as people (Battiste, 2013). Battiste (2013) writes, “educators must help students understand the Eurocentric assumptions of superiority within the context of history and to recognize the continued dominance of these assumptions in all forms of contemporary knowledge” so that they may help to decolonize the education system (p. 186). For educators, this recognition is also needed to be responsive to the calls to decolonize education and find their new responsibilities, including nourishing the learning spirits of those they teach.

The Canadian Council of Learning’s (CCL, 2009) final report on the state of Aboriginal Education provides alternative models of learning that nourish and contribute to the well-being of Indigenous people, physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. In consultation with FNMI peoples, the CCL developed distinct graphics to represent the learning and teaching systems of diverse Indigenous peoples. These models represent healthy educational relations in contemporary times, based on the wisdom of community members, and might be considered best practices. Building on Indigenous people’s traditional educational systems, which valued the roles and responsibilities of all community members, these findings act as guidelines to heal and nourish the learning spirit of all learners. Nourishing the learning spirit is a lifelong process:

Learning…as Aboriginal people have come to know it, is holistic, lifelong, purposeful, experiential, communal, spiritual, and learned within a language and a culture. What guides our learning (beyond family, community, and Elders) is spirit, our own learning spirits who travel with us and guide us along our earth walk, offering us guidance, inspiration, and quiet unrealized potential to be who we are. In Aboriginal thought, the Spirit enters this earth walk with a purpose for being here and with specific gifts for fulfilling that purpose. (Battiste, 2010, p. 15)

As learning is lifelong, learners may find different guides at different times of their lives and be guides themselves. Educators, if they are to contribute to the well-being of youth, can begin to respond to the calls to decolonize education by being nurturing guides (Anuik & Kearns, 2017). It is with the spirit of decolonization and nourishing the learning spirit that we designed a program rooted in a hope not only to help support a critical mass of educators to transform their practice, but also the educational system as a whole.

Our program: Decolonizing graduate education in Faculties of Education

The Indigenous-focused Master of Education cohorts

Our passion to engage in decolonizing work, led us to create a specialized graduate cohort in Indigenous education. The cohort is situated within a faculty of education with a commitment to social justice, a long-standing relationship with Mi’kmaq community members (Paul, Lunney Borden, Orr, Orr, & Tompkins, 2017), and a commitment to decolonization (Paul et al., 2017; Kearns, 2013). Among our faculty were professors who had the capacity to lead this work. Some of us are Indigenous or speak an Indigenous language, others are non-Indigenous professors, all of whom have spent a significant part of their teaching careers in FNMI communities, or have worked in rural, or urban settings with some Indigenous youth. Building on the Association of the Canadian Dean’s (AECD, 2010) Accord on Indigenous Education to support Indigenous focused education, the faculty seemed well situated to imagine a specialized Indigenous-focused graduate program. In order to imagine what decolonization in a graduate program might entail, we, the authors, drawing from our years of experience in Indigenous education, came together and brainstormed on whiteboards, markers in hand, what the goals of the program might be. The initial goals of the cohort are to:

• Examine the historical and contemporary effects of colonization on schools;

• Be aware of the pathologizing of Indigenous people that so frequently happens by society, the media, and other institutions;

• Understand how teaching and learning is conceptualized in Indigenous contexts;

• Explore multiple ways to understand colonization (anti-racist perspectives, decolonization, deconstruction and reconstruction);

• Theorize and problematize the concept of culture;

• See colonization as a continuing story (neocolonization, recolonization);

• Become familiar with Indigenous methodologies that inform curriculum development, leadership, and research;

• Examine case studies of successful educational practices in FNMI communities;

• Use Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing to challenge mainstream understandings of teaching and learning.

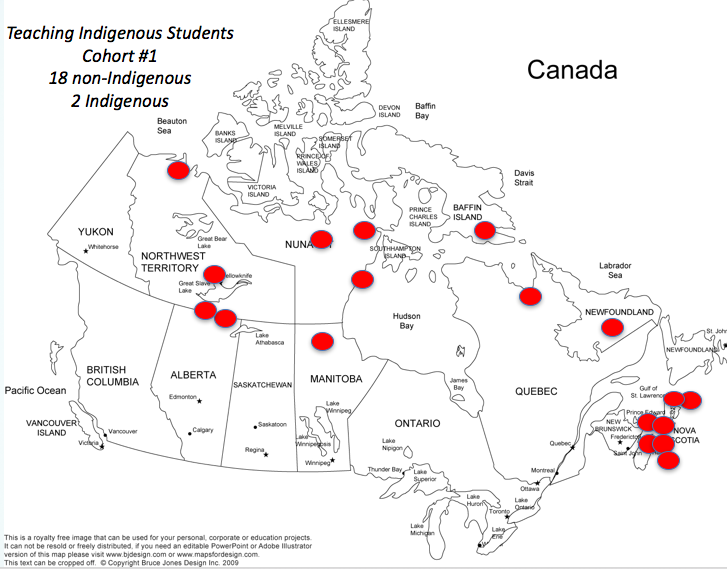

A call of interest was put out and we received an interest from over 20 participants who were teaching FNMI students across the country (See Figure 1; the 18 dots on the map represent the various communities in which graduate students are teaching). We generally cap the program at 20 to be able to develop better personal and professional relationships in our program, both in person and in our on-line learning environment. The graduate program consists of 12 core courses, with project, capstone, or thesis options available.

Figure 1. Cohort 1 map

The program is designed with part-time graduate students in mind. It is intended to be completed over a 24-month period with graduate students completing two courses in the summer and taking one course in each semester of the Fall / Winter / Spring terms. Two face-to-face courses take place on campus during the first summer of the program and provide the foundation for the subsequent 10 synchronous online courses that students from the cohort will continue to take together. This program is situated in the leadership stream of the Master’s program. The 12 courses include: Foundations of Education, Introduction to Research, Leadership and Administrative Theory, Dynamics of Change, Professional Development and Supervision of Instruction, and Critical Research Literacy, Administration of FNMI Schools, Cross-cultural Issues in Education: Working with FNMI Families and Communities, Infusing Indigenous Perspectives in Math and Science Education, Literacy in the Content Areas, Indigenous Languages and Community Wellness, and a Directed Study (Capping Experience). One of the overall goals of our Master of Education program is to cultivate educational inquirers and researchers, believing, like Lytle and Cochran-Smith (1992), that a teacher researcher stance towards pedagogy increases teacher agency. With that in mind, each graduate student develops an action research / teacher inquiry research plan which they enact in their final capping experience.

To date, our program has developed three Canada-wide specialized graduate cohorts for educators who are teaching Indigenous students and/or interested in Indigenous-focused pedagogy (2014-2016 Cohort 1; 2015-2017 Cohort 2; 2017-2019 Cohort 3). Cohort 1 had a majority of non-Indigenous graduates, while Cohorts 2 and 3 have a majority of Indigenous graduate students. We believe that the strong uptake to the Indigenous education cohort speaks to the need for educators working with FNMI students in diverse contexts across the country to deepen their understanding of decolonizing education.

Setting the tone to learn in a “good way”

As a faculty, we have been using self-study research (Kearns, Mitton-Kükner, & Tompkins, 2014; Tompkins & Orr, 2009) to examine how our relational and decolonizing pedagogy has enabled us to be successful in creating transformational spaces for social justice learning to occur. Palmer (1993) reminds us that effective learning for adults requires open, bounded, and hospitable spaces. He urges us to consider carefully the ways we invite people into the learning space, while reminding them that we will be asking them to travel with us to places where difficult conversations take place. Our explicit program design, beginning with the two face-to-face courses, allows us to build relational pedagogy. As one graduate student, Bobby, noted in a sharing circle conducted in 2016, “without that start, and the bonds that we’ve built, during those two first classes — I know I wouldn’t have been able to keep it up and I’m sure I’m not the only one…. it carried me through.” The program engages with Indigenous storytelling, via methods such as Storywork (Archibald, 2008), nourishing the learning spirit (Battiste, 2010; CCL, 2009), and St. Denis’ (2007) anti-racist framework. This approach helps to guide our explorations of schooling that examine issues of power, privilege, positionality, cultural capital, as well as colonization. We use a wide variety of learning strategies, including experiential learning, cooperative learning, small group discussions, talking circles, videos, guest speakers, and multiple ways of representing knowledge to engage learners. We consider ourselves facilitators, and, true to the root of that word, we see our job as making talking to each other, facile or easy. We know that deep professional learning will not happen if our adult learners feel judged, so we enter into the classes with a spirit of generosity that allows us all to be learners. We heed Battiste’s (2013) words that we are all, non-Indigenous and/or Indigenous, “marinated in Eurocentrism” (p. 6) and so we are really learning how to be in relationship with each other in a good way.

The Research: Methodology and Methods

A decolonizing framework is foundational to our graduate studies work and to our research. The importance of recognizing history with a view to understanding present conditions and future possibilities for Indigenous “self-determination, decolonization and social justice” (Smith, 1999, p. 4) is paramount. Smith reminds us that deconstructing Eurocentric, Imperialist, colonial versions of history and revealing the Indigenous counter-stories and perspectives is part of a decolonizing framework, but so is responding to the historical conditions that contribute to a vicious cycle of negative stereotypes that continue to perpetuate poverty, violence, and a lack of basic human dignities, such as clean water and safe housing. We are reminded that the work of decolonization is complex, multifaceted, and needs many people to work in a number of areas. Kovach (2009) says: “Indigenous researchers have acknowledged colonial history of Indigenous oppression and the political nature of Indigenous research” (p. 28).

In seeking to take up our responsibilities, this research aims to examine how specialized cohorts in Indigenous education, with their explicit focus on deep professional learning, might strengthen the capacity of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous educators to be effective in their contexts, whether that is teaching FNMI students in band-operated schools, public schools, or at the postsecondary level. Joyce and Calhoun (2010) noted in their research on professional learning that learning opportunities that are focused, sustained, and supported lead to increased teacher capacity in schools. This research has implications on multiple levels for seeking to understand how our work impacts teaching and learning. In our research, we thus ask:

1. How does a program with a clear decolonizing focus influence teachers’ practices, community engagement, sense of agency, curriculum possibilities, leadership, and possibilities for transforming school culture?

2. How has this program nourished the learning spirit (Battiste, 2013) of the educators themselves and the students teach?

We are beginning to answer these questions with the insights from our first cohort. In recognizing the complexity of adult learners, we acknowledge that many people who enter graduate studies are balancing work and life responsibilities in addition to graduate work, and not everyone’s path will be the same. So, although we started with 20 students initially, 12 students graduated within the 2014-2016 trajectory; some have since completed their M.Ed (2017), while others are on track, but are pursuing a thesis, and others had to step away from the program temporarily and are working on completing the last few credits required for graduation.

Our research methods and methodology align with Kovach (2009), who adheres to a constructivist view of knowledge, and employs a decolonizing perspective. The methods we employed to conduct our research draw upon Kovach’s (2009) work, in particular her use of “sharing circles” (p. 35) which she uses as part of her method in conducting Indigenous-focused research. Students were first introduced to talking circles in our courses, where we were mindful to introduce everyone to protocols for speaking, listening, being fully present, and cognizant of everyone’s voices being equal in the circle (instructor and student). The research sharing circle was modeled on how we often engaged in our classroom discussions, where everyone had the opportunity to share and give feedback. Participants were invited and consented to have their voices recorded for research. This approach was informed by the Mi’kmaw practice of mawikinutimatimk (coming together to learn together) which recognizes that everyone has something to learn and something to share (Lunney Borden & Wagner, 2013).

After the final presentations of the 12 graduating students from the first cohort, we used a sharing circle to initiate a discussion on how this program nourished their own learning spirits and helped them support and nourish the learning of FNMI students within their own contexts. We have used pseudonyms for the participants, and note the context in which they teach, their career stage and their role in the system, and if that has changed:

• Krista is a mid to late career educator, former guidance counsellor, currently working in a government leadership role in Nunavut;

• Ben was a teacher when he began the cohort and who quickly moved into a principalship, now in his second year, and is in the Northwest Territories;

• LeeAnn is an early career high school teacher, in a small town in Nova Scotia located close to two Mi’kmaw communities;

• Sharon is a mid-career college instructor in a large community in the southern part of the Northwest Territories;

• Shawn is an early career educator who began the cohort as an elementary teacher in the Northwest Territories and recently accepted a job as a vice-principal in a First Nations community in British Columbia;

• Larry is a mid-career educator teaching middle school in the Nunavik region of Quebec;

• Brianne is a mid-career secondary science educator who teaches in a Nova Scotia provincial school, which serves a high number of Mi’kmaw students;

• Suzanna, Erica, and Denise are all mid-career educators, who have taught at the elementary and secondary levels, and who teach in different Nova Scotia provincial schools, which serve a number of Mi’kmaw students;

• Bobby is a mid-career elementary educator teaching in a large fly-in community in Nunavut;

• Roxanne is a late career educator in Western Canada who is the principal of the school in which she previously taught as a teacher.

We received ethical approval from the university before proceeding with the sharing circles. We taped and transcribed the recording. We each read and coded these transcripts individually and then came together to crystalize our shared understandings and create themes. We also participated and shared our own learnings, since, as Kovach (2009) stipulates, reflexivity is important within qualitative research within Indigenous inquiries. Data for this first part of the study also comes from Program Evaluation Surveys that were e-mailed to the 12 students and were independently returned.

We thought it would be important to follow up with the students within a year of graduating to further reflect on the program and consider if or how it helped them decolonize in their own educational sphere of influence. We thus conducted a second sharing circle that six of the graduates were able to attend. Several sent regrets and we will follow up with them individually at a later date.

In conducting our research, we were mindful to consider and do research in a relational way, in a good way, and as Kovach (2009) asks us, to hear the voice of the Elder: “Are you helping us?” (p. 36). We hope we are responding to the best of our abilities at this time, though we may find different paths and have new and deeper understandings later. In conducting research to understand how we are and can better consider the decolonizing project, we are mindful of our desire to help and not harm Indigenous people and Nations.

Findings and Discussion

Here we share some of the themes that have emerged from our sharing circles in 2016 and 2017 with the first Indigenous-focused graduate cohort. It has been our privilege to journey with this dedicated group of professionals. In asking how the Indigenous focused cohort impacted the participants and their practices, a number of stories were shared on aspects of nourishing the learning spirit, teachers’ practices, community engagement, teachers’ sense of agency, curriculum possibilities, and leadership possibilities for transforming school culture. Participants also expressed a sense of hopefulness. These themes emerged through our analysis of the recordings of the sharing circles. Each of these themes is described in more detail below.

Nourishing the learning spirit

In debriefing after the final presentation in the summer of 2016, Larry reflected:

Two years ago we were like little tiny seeds…our instructors poured a big glass of water on us and… ideas started to germinate… all of us in this cohort have just blossomed…we talked this morning about a variety of different ideas [to decolonize education] and it just goes to show you what collaboration does, and… what the planting of a little idea can do. In these past two years…. “who benefit[s]?” “Our students.” And I think that speaks volumes about what we’ve accomplished between the summer of 2014 to the summer of 2016. (Sharing Circle [SC], 2016)

Larry shared a real sense of growth and having ideas blossom, and those ideas in turn helped the students that he taught, but he also implied that the learning shared by the group helped all the students these educators reach and teach. Brianne also shared that she has “grown so much as a teacher…I feel so blessed to have had this opportunity to share this journey with you all…I’m very, very thankful. The connections and the relations were awesome” (SC, 2016). The learning community helped nurture her growth as an educator as well.

Transformation takes place over time. Denise recognized that everyone entered the program with some similar goals claiming, “we all had this same goal of trying to be better, better educators for our students…I can remember the first class in the summer…not even realizing [how much I didn’t know] about colonization and decolonization,” and by the end of the program she said “now I just feel…so much more capable of including all of the students I teach everyday” (SC, 2016). Denise introduced talking circles in her classroom where Indigenous youth represent only a small number of her students, but she found this holistic practice was good for all her students, as did her two research mates, Suzanna and Erica, who tried the same practice in their classrooms at their different schools. Suzanna shared that “changing one or two little things that you do in your practice everyday…makes you a better person…[a better educator]” (SC, 2016). Erica stated that she was “thankful” and that she is “hoping to bring a lot of what [she’s] learned to make positive changes within our school” and wants “to continue on with our project…hoping to make that spread school wide” (SC, 2016). The cohort found ways to support each other to try and incorporate more Indigenous practices, and they learned that this type of nurturing was good for all youth, as well as themselves. As Roxanne said: “everyone was supportive, and so willing to share, I want to say a big ‘thank you’” (SC, 2016). Roxanne’s spirit was nourished and energized by being able to connect with others and find a supportive community. In fact, upon reflecting almost a year later, Roxanne said:

I find with nourishing my learning spirit I’m a lot more open. I find there’s a lot of hope. I seem to be very sensitive after taking this course [program]. A big part of my project was having Elders in the school, and we kind of pulled from that to a culture room that we started and now we have a classroom that looks like a log cabin. That’s where a lot of the culture happens now. (SC, 2017)

Elders had been invited into the school prior to her work in our program, but since graduating, a permanent place had been created in the form of a cultural / cabin atmosphere classroom. So the Elders are welcome in the school and the youth can easily connect with them. Reflecting back on her time in the program, she recalls: “I would rush home and look forward to this course.” Now that the program has ended, she shared that she missed it and feels a professional “void” (Roxanne, SC, 2017). In connecting to another participant’s sharing, Roxanne said:

When you mentioned the PLCs [professional learning communities], LeeAnn… The teachers are up to their eyeballs in literacy. Our last two PLCs I got a hide for the school and we started doing beading. All of the teachers, and the guys too, we started making moccasins. It’s a work in progress, but they just really enjoyed that. I was surprised they look forward to our PLCs now; it’s moccasin making not literacy. They needed that break…that time to just talk about things and enjoy themselves, I guess wellness. (SC, 2017)

Roxanne has used her own feeling of well-being and being nurtured to create spaces for her students in her school to be engaged with Elders, but has also created practices to enable her staff to be nourished. She is using Indigenous cultural practices and honouring their power in her school’s PLC. Arguably, these cultural practices are a form of literacy, but ones not always recognized by those who adhere to traditional concepts of literacy (López-Gopar, 2007). Indeed, practices and traditions from the First Peoples of this land are nourishing the spirits of our cohort members and beyond.

Teachers’ practices and curricular possibilities

One of the program’s intents is to help empower and strengthen educators’ abilities to decolonize their practices and curriculum, to have people question history and the narratives and images we are presented with about Indigenous people. To that end, LeeAnn shared:

My historical knowledge definitely increased. It [this program] opened my eyes because I did a major in history and it opened my eyes to how much was missing from those courses that I took as a history major in terms of Indigenous history and colonization in Canada. That really changed things for me. I feel like when teaching social studies now, I have a much different perspective and many resources and videos that were shared…I use on a daily basis. (SC, 2017)

LeeAnn was open to (re)learning history and perspectives different than the ones she had learned from mainstream curricula. To that end, she is now critical of the curricula that she presents to her students:

I look at my curriculum differently now. Each lesson that I teach…I have a different perspective on why I’m teaching what I’m teaching…and how to make it more inclusive, to represent Indigenous learners, but also just the learners in my class from various communities, wherever they come from. (LeeAnn, SC, 2017)

LeeAnn’s practices as an educator have shifted in that she is a much more inclusive educator. She is aware of different narratives and the diversities of the youth in her classroom. Sharon, an adult educator at the college level, has also found her teaching practices have changed and she has been able to try new curricula as well. She explains that since completing the program, she has

…initiated two culture camps, one in the first term, and one in the second term, and this past one I have asked students to take part more. For example, I have students making caribou stew, I have students share their knowledge of traditional Inuit games. One student brought his drum and shared a song. (Sharon, SC, 2017)

As a non-Indigenous educator, Sharon has opened up the educational space for her own students to share aspects of their culture and for that to be honoured in their educational journey. As Donald (2009) explained, when we let go of the idea of an educator being all knowing, an expert at everything, and we take the opportunity to learn from as opposed to learn about Indigenous people, authentic and engaging curriculum changes can take place. If we embrace the idea of an educator that can learn alongside others, more can be shared.

The confidence of having a critical cohort committed to decolonization helped support an important change at the school level with regard to resources. Systemic changes are indeed needed to decolonize education. The efforts taking place in different classrooms and in different schools are certainly heartening, though there is still a long way to go.

Engagement with community

Colonial education prioritizes Eurocentric ways of knowing, being, and doing, while carefully avoiding any acknowledgement of local Indigenous communities’ language(s), knowledge, and ways of being. Long serving Inuit educator and Elder Peesee Pituluak laments “You shouldn’t have to look outside the classroom window to know you are in Nunavut” (personal communication, July 21, 2009). Too often FNMI communities are (un)consciously seen from a deficit point of view by non-Indigenous educators. It is indeed a decolonizing moment when Indigenous communities and families can be seen from an asset perspective and as a potential place of curriculum-making and relationship-building. Graduate students in this cohort talk about how they are able to see Indigenous communities and/or Indigenous families relationally. Roxanne speaks of her leadership effort to bring in more Dene language into the school curriculum.

With us here, as far as hopefulness and decolonizing, the language feature [is vital]...we now have a Dene teacher who comes to the school and teaches the Dene language. I find here we bring in culture any way we can. Even the division seems to be moving forward with the FNMI education. (SC, 2017)

Roxanne shows that although the community and its people are standing right in front of educators, sometimes a Eurocentric educational system prevents them from seeing the possibilities of partnering with Indigenous knowledge holders. As a long-term resident of the community, she describes how this cohort has helped her see previously hidden possibilities for engagement. “I know I have taught in the community and been in the community for years, but the cohort really opened my eyes up and made me think differently” (SC, 2017). Once the paradigm shifts, community engagement and community representation in the school can increase.

Likewise, Ben sees the possibility of the community and importantly the land being a place of valuable learning for his Dene students.

I highly encourage them [the staff] to have a connection to the Dene Curriculum for the NWT. I think this is the hope to bring students back to more traditions. This week is a great example. I’ll be driving the van down to the river and doing some basket weaving, skinning animals, out trying to catch beaver, rabbit, moose, or bear, exposing them to that as much as possible. There is a balance you need to find; it can’t be all culture all the time.... There is lots of hope on keeping the younger generation in touch with their culture, to slow down and keep it alive as much as possible. There is an inevitable connection to the western world now, there’s no going back. It’s just keeping that traditional culture alive and well…. I would be hoping to do that as an agent for decolonizing education. (SC, 2017)

Educators’ abilities to see and incorporate aspects of Indigenous culture in their schools and curriculum are an important part of decolonizing education. Ben came to these realizations in discussion with his colleagues in the cohorts, particularly Roxanne. Sharon also was able to make more community connections, and while she cannot travel to the diverse FNMI communities from which her students come, she knows that they themselves bring community knowledge with them into the classroom. Where previously she might have left that Indigenous community knowledge at the door of the classroom, she now intentionally makes decolonizing spaces. As discussed in her work with the culture camps, Sharon notes that she had to initiate this activity and in so doing she is interrupting the Eurocentric agenda of post-secondary institutions.

Once the colonial narrative has been interrupted, it is difficult, if not impossible to return to it. Krista comments on how she examines engagement with community and inclusion of community voices in school processes with more of a critical stance. She looks for the presence and participation of Indigenous people and is more aware of their absence and willing to challenge those omissions. She explains:

I spent the last week working with a Pan-territorial group to create some recreation-programming curriculum. It’s funny when I looked at the lens that I approached that with now. I was like ‘you didn’t start with Indigenous indicators or Indigenous people to create this curriculum?’ I don’t think I would have had that awareness before. (SC, 2017)

Teachers’ sense of agency

As teacher educators deeply involved in teaching for and researching about social justice, we know the incredible power of teacher agency. We note many participants in the Indigenous cohort face high levels of school and community challenges, due in large part to the enduring colonial legacy. Many teach in remote communities where there are few if any second-level supports, such as access to school board mentors or visiting consultants. It is therefore heartening to see the increased sense of teacher agency these educators speak about. The economic, social, and historical conditions of the communities in which many teach have not changed, but they themselves have been changed by their participation in this cohort. Shawn speaks of his excitement and confidence.

First off, StFX [Saint Francis Xavier University] totally changed my life. Every day that goes by I notice a huge difference in how I approach education. As a Vice Principal now, it’s very exciting to be a part of a lot of different committees and choices. In terms of nourishing the learning spirit of others, where I live right now, we just finished a children’s cultural celebration and I was dancing in part of that. I was helping out…I always had a passion before, but StFX helped me do that in more professional and sophisticated manner. (SC, 2017)

The deep professional learning that was part of a cohort intentionally focused on decolonization over a 2-year period has been considerable. Roxanne speaks to the depth of her new knowledge as well: “My knowledge base has really increased since I’ve taken these courses, with the books that we have read, and the experiences that you as instructors brought to the courses” (SC, 2107).

With increased knowledge and skills come an accompanying confidence that allows the participants to act as a supporter and advocate in Indigenous education. For example, LeeAnn was, by her own admission, feeling intimidated enrolling in a Master’s program and unsure of her ability to be successful (personal communication, July 16, 2014). The learnings in the cohort, however, have given her the confidence to be an actor in her classroom, and in the school. “Now I feel more comfortable trying new things in my classroom and I didn’t have that before [the program]” (LeeAnn, SC, 2017). For Krista and Shawn, the agency they now feel comes from their sense of knowing that they stand on deep teachings from Elders, the writings of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars who advocate for critical pedagogy, and the support of Indigenous and non-Indigenous colleagues who have worked with and alongside them. Krista states

I can say that for me I went into the program knowing that learning about Indigenous education was the right thing to do, and now I can justify it pedagogically. Not to brow beat anyone, like Shawn said I don’t want to alienate anyone, but when a dialogue happens… it’s important in academic circles to be able to refer to [for example] Marie Battiste. (SC, 2017)

Krista can now articulate with confidence to others what she believes to be true about Indigenous education. Shawn concurs,

Every day that goes by I notice a huge difference in how I approach education…I was using some Heiltsuk in the classroom. I always had that passion before, but StFX M.Ed program helped me do that in a more professional, sophisticated manner…”

Leadership and possibilities for transforming school culture

Graham Smith (2000), Maori educator and scholar, speaks of the power that comes from a leader knowing what is it that is to be done from amid several choices. As this cohort was nested within a leadership stream, all graduate students were exposed to decolonizing models of leadership. Traditional Eurocentric leadership theory has tended to use models that focus on the individual leader and then to see leadership embedded in hierarchical structures. An explicit goal of the leadership core courses was to help the graduate students focus on shared and distributed models of leadership and leadership as process. As such, the participants named and saw their teaching as leadership. LeeAnn expressed, “I approach my teaching much differently since completing the program” (SC, 2017). Lee Ann sees herself as using her leadership beyond her classroom outwards to the school community. When she has been able to do this, she has noticed the positive effects. “The interest [in including First Nations’ perspectives] is contagious. People will pick up on that and come to you. I definitely notice that with people in my school and family members” (LeeAnn, SC, 2017).

Shawn, in his new role as vice-principal, spoke of how he is asserting his leadership to create a process to discard outdated and colonial resources. He assisted in reviewing very outdated resources that depict Indigenous peoples in stereotypical and inaccurate ways. He says now: “I’m way more inclined to step up to the plate in terms of pedagogical discussions concerning resources, and that’s something I definitely learned from StFX that I am passing along” (SC, 2017).

Sharon recognized her teacher leadership and is willing to embark upon changing the climate in her classroom, to the extent possible in her role as instructor:

Through this course I realized that we need to make the learning place that we are in feel more like family and like home. Students are really connecting to it and I think the stats prove it this term, they are staying and they are really engaged in their courses. It’s really exciting. When I think about hopefulness, I think that I am going to try to keep including the students and appreciate and affirm them for who they are. (SC, 2017)

In so doing, Sharon noted that her modeling of how to set up classes in a more relational manner is influencing other faculty to adopt similar ideas. As such, she is demonstrating the ability to lead by example, which is a very powerful element of authentic leadership.

Many graduate students use their formal and informal leadership roles to advocate for decolonization in their schools. Ben, relatively new to the principal’s role, demonstrates how he enacted leadership to transform how the school viewed the home language:

there’s a lot…the one thing I want to focus on is the language in the schools. The most challenging part for me is that I had to accept the fact that I had to start learning the language, that’s never been easy for me even learning French on my own. Having students see me do that on the morning announcements or saying good morning — it’s the little things that I think matter. I never would have done that if I wasn’t in this program. (SC, 2017)

The power of valuing Indigenous languages is paramount. Battiste (2013) reminds us that cognitive imperialism, residential schools, and colonization have all impacted Indigenous languages; some have been lost, others are in danger of not surviving, and some continue to be integral to Indigenous communities. As non-speakers of Indigenous languages, especially those in leadership roles, whether we bring in Elders or speakers into schools and/or an attempt to speak an Indigenous language and show respect of the deep knowledge that comes from Indigenous languages, honouring Indigenous languages is integral to transformation and change. The TRC’s (2015) Calls to Action (#14 specifically) have emphasized the importance of Aboriginal languages and affirm the importance of their preservation, revitalization, and strengthening (p. 2).

Hopefulness

The educators in our study said again and again that the support they found in the program and with their peers gave them more hope in doing their work. Overall, reflecting back on the process, high school teacher LeeAnn said:

I feel like I have a higher level of hopefulness, as Roxanne had said. I feel more eager and positive in looking for more ways to incorporate Indigenous knowledge into the school. I feel like maybe I wouldn’t have been seeking that out as much. I feel like the program gave me tools and resources, and I think a sense of eagerness and a positive approach towards that. It’s not something that is seen as an add-on, it’s something you want to do. You want to be continually incorporating that knowledge into your lessons and into your school and you approach that with a real positive attitude. (SC, 2017)

LeeAnn is acting as a change agent as part of who she is now and how she sees the world. Others too have had more hope brought to the fore. Krista was the school guidance counselor for the two years she was in the program and recently became a suicide prevention advocate. She reflected:

Another thing that it’s done is it’s brought me closer to the Inuit educators that I work with. I am more confident and less shy in working with them, which increases my learning from them. In terms of hopefulness, with suicide prevention — when I think about how I felt about suicide prevention a year ago and how I feel today, it’s totally different. (SC, 2017)

As teacher-educators in the program, we find this remarkable. Many of our graduates work in communities with a lot of trauma, where the intergenerational impact of residential schools is evident, where there is environmental degradation and suicide rates are high. The experiences some of our educators have been through and what they have experienced and witnessed is hard, and some of them shared that it broke their hearts and made it hard for them to continue to teach at times. So we cannot underscore the importance of listening and being present to one another throughout the cohort. The relationships built in the cohort really helped participants to connect with Indigenous people in meaningful ways. When Krista spoke of hope, even though she is dealing directly with suicide prevention, in a jurisdiction where the suicide rates for Inuit youth are higher than the national average, she explained that she feels that a new space is opening up and people are being more open to Indigenous people and knowledges, and she felt the pride will help contribute to greater well-being. Battiste (2010) wrote that “[t]eaching is the psychology of hope, and hope is a cause and consequence of action…it believes that vast problems can yield to several small solutions” (p. 175). For educators in our cohort, taking small actions has given them considerably more hope.

Reflecting on our Learning

We are reminded that decolonizing work has a spiritual dimension to it, as Mi’kmaw Chief PJ Prosper so eloquently stated, “moving from the head to the heart” (personal communication, March 4, 2015). The experience of working with and alongside Indigenous people has deeply impacted our educators. The voices of our 12 non-Indigenous graduate students attest to the power of deep, intentional, and relational graduate education. Perhaps part of the way we unmarinate ourselves from colonization is through ongoing long-lasting conversations and experiences. If working towards reconciliation needs to be taken up by non-Indigenous people, then experiences where they are in contact and open to the knowledge systems of FNMI communities are integral to that process. In deepening their understandings of FNMI peoples and communities, feeling supported in their work, these educators are better able to nourish the children they teach, and continue teaching in challenging heartfelt situations.

Our graduates found support within the cohort to decolonize their sphere of influence. This is not to say that they did not meet with resistance. In response to the question, ‘are you facing resistance from colleagues?’ Ben replied:

Absolutely. It [the program] gives me the confidence to be able to argue that what I am saying is right. Although [the staff] they bring up a lot of good points… [why do] we focus on culture so much when some students are two or three levels below the literacy and math level? [Before] I wouldn’t know what to say, I probably wouldn’t be in this position without the program. It had given me the tools to say, ‘I understand that, but it’s important to have the strategies to incorporate the culture into the literacy.’ (SC, 2017)

In taking up a leadership position, Ben now has the confidence and ability to speak back to concerns around programing. Shawn also shared that having studied “decolonization for two years,” he is much more able to take on a “leadership” and “advocacy role” now that he understands the “dynamics of change” and places a real emphasis on “inside” as well as “outside” the classroom practices (SC, 2017).

Reflecting on our own experiences as teacher-educators, we too have grown alongside our students. We have a better understanding of and are humbled by the complexity and diversity of the contexts in which our students teach. We have had our own learning journeys nourished by the relationships we have been drawn into through our interactions with our graduates. The vulnerabilities exposed in the stories they shared of their classrooms, communities and contexts, deeply touched our hearts, minds, bodies, and spirits. As teacher-educators, there is often an expectation that we have all the answers; however, if answers emerged, they came out of the collective dialogues made possible through the level of relationality in our cohort. These teaching experiences have also created a space for us to share more of who we are as Indigenous teacher educators and allies in ways that are not always possible in more mainstream settings. We too have found more hope in the power of graduate studies to decolonize education.

In Davis’ (2010) collection, entitled Re/Envisioning Indigenous — Non-Indigenous Relations, there is an image of a bundle of twigs; one twig is fragile, but many are strong. Mohawk Elder Jake Swamp’s teaching about the twigs reminded Davis that there is “an urgent appeal for all to pick up our responsibilities as human beings for the sake of survival of all life…a desire to see longstanding injustices resolved and a mutual, respectful future realized” (pp. 9-10). In working towards reconciliation and decolonizing education, we acknowledge there is much work to do that will require a critical mass of educators to work on various aspects of decolonization in various places and spaces. Our cohort participants are seemingly more able to take on and continue this decolonizing work. In recognizing and valuing Indigenous people and cultures, the cohort participants are better positioned to show leadership and play an active role in reconciliation. When non-Indigenous people have acquired cultural humility and when Indigenous people feel that their voices can be respectfully heard, we will truly be in a place where dialogue can occur and reconciliation can take place.

References

Anuik, J., & Kearns, L. (2017). Métis and Ontario education policy: Educators supporting holistic lifelong learning. In J. Reyner, J. Martin, L. Lockard, & W. S. Gilbert (Eds.), Honouring our teachers (pp. 61-76). Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University.

Archibald, J. (2008). Indigenous storywork: Educating the heart, mind, body, and spirit. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Association of the Canadian Deans of Education (ACDE). (2010). Accord on Indigenous Education. Retrieved from https://www.oise.utoronto.ca/aboriginal/UserFiles/File/FoE_document_ACDE_Accord_Indigenous_Education_01-12-10-1.pdf

Battiste, M. (2013). You can’t be the global doctor if you’re the colonial disease [CAUT Lecture]. Retrieved from https://www.caut.ca/sites/default/files/you-cant-be-the-doctor-if-youre-the-disease-eurocentrism-and-indigenous-renaissance.pdf

Battiste, M. (2010). Nourishing the learning Spirit. Education Canada. Canadian Education Association, 50(1), 14-18. Retrieved from http://m.cea-ace.ca/sites/cea-ace.ca/files/EdCan-2010-v50-n1-Battiste.pdf

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Saskatoon, SK: Purich.

Blackstock, C. (2010). Reconciliation means not saying sorry twice: Lessons from child welfare in Canada. From truth to reconciliation: Transforming the legacy of residential schools. Ottawa, ON: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

Canadian Council on Learning (CCL). (2009). The state of Aboriginal learning in Canada: A holistic approach to measuring success. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Council on Learning. Retrieved from http://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education2/state_of_aboriginal_learning_in_canada-final_report,_ccl,_2009.pdf

Davis, L. (2010). Introduction. In L. Davis (Ed.), Alliances: Re/envisioning Indigenous – non-Indigenous relations (pp. 1-12). Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Donald, D. (2009). The curricular problem of indigenousness: Colonial frontier logics, teacher resistances, and the acknowledgement of ethical space. In J. Nhachewsky & I. Johnston (Eds.), Beyond ‘‘presentism’’: Re-imagining the historical, personal, and social places of curriculum (pp. 23-39). Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense.

Joyce, B., & Calhoun, E. (2010). Models of professional development: A celebration of educators. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Kearns, L. (2013). The Ontario First Nation, Métis and Inuit education policy framework: A case study on its impact on the lives of Indigenous and Non-Indigenous administrators, teachers and youth. In Education, 19(2), 86-106.

Kearns, L., Mitton-Kukner, J., & J. Tompkins. (2014). LGBTQ awareness and allies: Building capacity in a teacher education program. Canadian Journal of Education. 37(4), 1-26.

Knockwood, I. (2001). Out of the depths: The experience of Mi’kmaw children at the Indian Residential School at Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia. Black Point, NS: Fernwood.

Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous methodologies. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Loomba, A. (2008). Colonialism / Postcolonialism. New York, NY: Routledge.

López-Gopar, M. (2007). Beyond the alienating alt]phabet literacy: Multiliteracies in Indigenous education in Mexico. Diasposa, Indigenous and Minority Education. 1(3), 159-174. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15595690701394758

Lunney Borden, L., & Wagner, D. (2013). Naming method: “This is it, maybe, but you should talk to…” In R. Jorgensen, P. Sullivan, & P. Grootenboer (Eds.), Pedagogies to enhance learning for Indigenous students (pp. 105-122). New York, NY: Springer.

Lytle, S., & Cochran-Smith, M. (1992). Teacher research as a way of knowing. Harvard Educational Review, 62(4), 447-473.

Milloy, J. (2006). A national crime: The Canadian government and the Residential School system 1879-1986. Winnipeg, MB: The University of Manitoba Press.

Palmer, P. (1993). To know as we are known: Education as a spiritual journey. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Paul, J. J., Lunney Borden, L., Orr, J., Orr, T., & Tompkins, J. (2017). Mi’kmaw Kina’matnewey and Mi’kmaw control over Mi’kmaw education: Using the master’s tools to dismantle the master’s house? In E. A. McKinley & L. T. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of Indigenous education. New York, NY: Springer.

Smith, G. H. (2000). Protecting and respecting Indigenous knowledge. In M. Battise (Ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision. Vancouver, BC: UBC Pres.

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies. London, United Kingdom: Zed Books.

St. Denis, V. (2007). Aboriginal education and anti-racist education: Building alliance across cultural and racial identity. Canadian Journal of Education, 30(4), 1068-1092.

Tompkins, J., & Orr, J. (2009). “It could take forty minutes: It could take three days”: Authentic small group learning for Aboriginal education. In C. Craig & L. Deretchin (Eds.), Teacher learning in small-group settings. Teacher Education Yearbook XVII (pp. 261-277). Lahnam, MD: Rowan & Littlefield.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to action. Ottawa, ON: Author.