AN EXPLORATORY CASE STUDY OF ONE EARLY CAREER TEACHER’S EVOLVING TEACHING PRACTICE IN NORTHERN CANADA

There is considerable interest in understanding more about how pre-service teachers (PSTs) grow and change as they move from teacher education programs into their first years of teaching (Beck & Kosnick, 2014; Cochran-Smith et al., 2012; Caudle & Moran, 2012; Grossman et al., 2000; Jones & Enriquez, 2009). We conducted a longitudinal study from 2012 to 2016 examining the transfer of learning about literacy practices from a preservice teacher education program to the secondary classrooms of early career teachers (ECTs). Emerging from this study and our observations on the influence of our teacher education program intersecting with the new teaching contexts of ECTs, we explore how one ECT, Don,1 described his teaching practice as he made the transition from a Bachelor of Education (B. Ed.) program2 in Atlantic Canada to the first years of teaching in an Indigenous community in northern Canada. The purpose of this paper is to highlight the possibilities of paying attention to the particularities of individual cases of ECTs, and suggest implications for teacher education programs that have PSTs who go on to teach in northern Indigenous communities.

Re-thinking teacher education programs for ECTs teaching in Indigenous communities

The authors work in a teacher education program that has deliberately focused its efforts to develop PSTs’ critical consciousness in ways that are mindful of and committed to understanding the complex social conditions of the communities in which they will teach. Equity and social justice comprise one of the four program themes, embedding an examination of cultural diversity, anti-racism, Indigeneity, white privilege, gender, and poverty into key required courses and field experiences. Students are asked to examine their own privilege and to consider who is and who is not well served by the current education system, and to design learning experiences that redress marginalization (Olson, 2008). Over half of the faculty members who are part of this program have had significant teaching experiences alongside Indigenous peoples, and others have worked in cross cultural situations of high poverty and / or cultural diversity.

We conceptualize reconciliation, drawing upon the principles outlined by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, as a responsibility to “sustained public education and dialogue, including youth engagement, about the history and legacy of residential schools, Treaties, and Aboriginal rights, as well as the historical and contemporary contributions of Aboriginal peoples to Canadian society” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015b, p. 3-4). With many faculty members committed to notions of reconciliation and decolonization of schools, Indigenous and non-Indigenous B. Ed. students learn about the oppression experienced by Indigenous peoples and have opportunities to think about how to infuse Indigenous knowledge, treaty education, and other decolonizing actions into their teaching as part of their teacher development.

ECTs in northern Indigenous communities: A review of the literature

This review of the literature has two main sections; one highlights relevant aspects of the vast literature on the transition from teacher education programs to first years of teaching for (mainly southern, urban) ECTs, and the second examines the literature for findings related to teacher education and ECTs in remote Canadian and Indigenous communities.

ECTs’ development of teaching practices

ECTs find that learning about the contexts of their schools is one of the biggest issues they face, especially when that context is very different from their own school experiences. McCormack, Gore and Thomas (2006) asked first year teachers to keep a journal, and found they wrote extensively about the context of their schools. One teacher stated, “Nothing I did at uni[versity] prepared me for this!” (p. 103), and the theme of feeling overwhelmed by the unfamiliarity of the new context is commonly reported by ECTs (Thomas & McCormack, 2002, as cited in McCormack, Gore, & Thomas, 2006).

There has been considerable research into ECTs’ practices and how preservice teacher education program can best meet the needs of soon-to-be ECTs (Cochran-Smith et al., 2012; Darling-Hammond, 2006, 2012; Flores & Day, 2006). Many have noted that time is a factor in teachers’ professional development as teaching is a multifaceted undertaking. “Learning to teach, as Feiman-Nemser (2001) suggested, requires pulling together strands of understandings and skills” (Wood, Jilk, & Paine, 2012, p. 2), a complex task that highlights the need for strong knowledge of content and pedagogy, as well as pedagogical content knowledge (PCK, Shulman, 1986). Grossman et al. (2000) found that ECTs actually increase and refine their use of pedagogical tools learned in teacher education programs after their first year of teaching, rather than simply discarding those tools, as is sometimes suggested. Their work indicates the importance of determining what capacities are the most important to develop in teacher education programs and how best to develop them. DeAngelis, Wall and Che (2013) noted the “complex interplay…between preservice preparation and mentoring and induction support” (p. 353) and its impact on ECTs’ career decisions.

McCormack, Gore, and Thomas (2006) noted that first year ECTs in their study “continued to find enacting a beginning repertoire based on the pedagogies learned and modeled in their teacher education challenging” (p. 110). Barnatt et al. (2016) identified two sets of factors in their review of the literature regarding ECTs’ decision-making: “[1] those involving teachers’ expectations about teaching practice and their subsequent sense of efficacy and emotional well-being…and [2] those that allow novice teacher to exhibit agency and…[to] persevere” (p. 9). Barnatt et al. (2016) found the ECTs in their study all encountered “disequilibrium” (p. 25) in their school contexts, and that the varying degrees of sense of agency each teacher felt were critical to the response each made. In other words, “the interplay between a teacher’s identity and agency was key” (p. 25).

While this literature is helpful for understanding how teacher education programs can support PSTs in becoming ready to teach in a general sense, it is silent on the topic of ECTs in northern Indigenous communities. There is a gap in this literature regarding the rich, beautiful, inspiring, and distinct strengths that these communities offer to ECTs in terms of becoming teachers who derive a sense of community and meaning from their practice. There is also a gap regarding the challenging situations in which non-Indigenous ECTs confront complex issues such as poverty, cultural differences, and geographic isolation in remote northern Indigenous communities in Canada. The following section addresses the literature on this critical topic for Canadian teacher education programs.

ECTs in northern Canadian Indigenous communities: Lessons for teacher educators. There is a long history of non-Indigenous ECTs in Canada heading north to teach, often for just a few years before moving to a larger, more southern community. Many feel “overwhelmed and underprepared” (Harper, 2000, p. 153). A large study critiquing the Ontario Ministry of Education’s Aboriginal Education policies (Cherubini, Hodson, Manley-Casimir, & Muir, 2010) found there is a crisis in education of Aboriginal students in Ontario, Canada’s largest province. The crisis is described as multi-faceted but one feature salient for this paper is the lack of appropriate knowledge and background new teachers bring to schools in Aboriginal communities. Cherubini et al. (2010) cite Ladson-Billings’ (2006) call for teachers to gain “culturally relevant academic knowledge to address the cultural capital of all students” (p. 334), and they link this call firmly with teacher education:

Without a profound investment in the re-education of in-service teachers and pre-service teacher candidates, the predominant experience of Aboriginal children will effectively undermine their respective communities who are actively engaged in building their children’s capacity to be self-determining. (Cherubini et al., 2010, p. 330)

There are examples of teacher education programs that are making this investment. Ladson-Billings (2014) described how she has developed courses which include culturally relevant pedagogical strategies and a “sociopolitical edge” (p. 80) to engage PSTs in gaining knowledge and understanding of African American, Latino, and immigrant cultures, along with relevant approaches for teaching in schools with children from these populations. We note a lack of Canadian articles or other publications describing how teacher education programs are incorporating mandatory Indigenous courses and other strategies, and hope to see this gap addressed.

The imperative for teachers in Indigenous schools to be highly knowledgeable and skilled in culturally relevant pedagogical practices and choices of materials involves the need to infuse teaching practices with Indigenous knowledge (Battiste, 2002, 2013). Wiltse (2015) urged a “consideration of how Aboriginal students’ “funds of knowledge” (Moll, Amanti, Neff, & González, 1992) from home and community networks can be utilized to reshape school literacy practices” (p. 61). A funds of knowledge approach invites a wider range of texts and literacy practices, “acknowledg[ing] that minority children, like their majority classmates, have participated in social practices in their families and communities, and it urges schools and teachers to connect school learning to children’ s out-of-school learning” (Marshall & Toohey, 2010, as cited in Wiltse, 2015, p. 61).

Wotherspoon (2006) noted that cultural relevance in terms of pedagogies and materials might not be sufficient: “For any teacher working in an Aboriginal community context, there are strong pressures to transform their actions well beyond the simple introduction of curricular materials and pedagogical styles deemed appropriate for Aboriginal learners” (p. 677). We agree with Wotherspoon that more is needed than appropriate reading materials, for example, and also with Berger (2007), who found that good intentions and caring about one’s students are not enough. While these are important, they must be underpinned by an awareness of why change is needed, and what more is needed. “The development of a socio-political consciousness is vital” (Aylward, 2007, p. 3) in order that ECTs (and all teachers) avoid reproducing the same colonizing forms of schooling that have existed for hundreds of years. Interrupting the discourse that reifies the school system’s foundation of Eurocentric curricular knowledge is challenging but important work. In our B. Ed. program, we see the challenges of this work each day. Staying with it, whether as a teacher educator in a program such as ours, or as an ECT in a northern community, calls for particular qualities of perseverance and flexibility. Berger (2007) suggested, “A high level of commitment, but also reflection, growth, advocacy, and collaboration with Inuit [and other Indigenous communities], is needed” (p. 1).

Wotherspoon (2006) advocated, “teachers must negotiate the difficult terrain that interconnects the often disparate and multifaceted worlds of school, economic requirements, and social experiences” (p. 676). This presents a challenging negotiation for ECTs in the context of communities that have endured struggles with colonization and racism, and in which schools are often seen as sites of change for next generations. One way forward is suggested by Aylward (2007), who highlighted the importance of place in her discussion of the Nunavut education system, suggesting that “educators and policy makers deliberat[e] upon constructions of place as they collide with constructions of culture” (p. 6). Recognizing place as a central organizing feature of curriculum is one potential outcome of developing the socio-political consciousness Aylward calls for. Teacher education can play a role in promoting this perspective among PSTs.

One of the 94 calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada (2015a) is that education should be recognized as a site of reconciliation. To better prepare ECTs for teaching in northern Indigenous communities, teacher education needs to rethink coursework and field experiences in B. Ed. programs, with an emphasis on preparing individuals for specific schools and communities, and the possibility of requiring additional qualifications for new teachers in northern Canada, perhaps in the form of community-led initiatives (Harper, 2000). Another response to this call to action is for faculties of education to work in long-term partnerships with Indigenous communities to support community members to obtain B. Ed. and M. Ed. credentials to work in their home communities (Murray-Orr & Tompkins, 2013; Burleigh, 2016). Teacher education programs must also work to “better address Aboriginal issues in education and better prepare non-Indigenous teachers for work outside of southern urban centers…by facilitat[ing] the integration of Aboriginal perspectives across the curriculum” (Burleigh, 2016, p. 88). With these important recommendations in mind, we investigated the experiences of one ECT in a northern Indigenous community, with the goal of finding new ways to engage in rethinking B. Ed. programs.

Theoretical Framework

Given the larger framework of our inquiry into the developing PCK of early career content area teachers as they move from the supports of their pre-service teacher education programs into the contexts of schools and full time teaching, we draw upon Shulman’s (1986) conceptualization of PCK to support our understanding of an ECT’s growth in a northern Indigenous Canadian school setting. PCK, according to Shulman, is understood as one of three kinds of teacher knowledge, the other two being content knowledge and curriculum knowledge. For Shulman, PCK is a consciousness of forms, or methods, of representation that are best matched for the teaching and learning of content within subject areas.

Of particular importance to our inquiry is our attempt to better understand, and document, how the knowledge of ECTs grows by paying attention to their emphasis on how they teach in response to the particularities of the learners they teach within specific settings. While we acknowledge that teacher knowledge, including PCK, grows over time as teachers experientially gain depth and breadth, we are also mindful about the importance of context and how it informs PCK development. Flores (2008) noted, “The ways in which teachers learn and develop in the workplace are dependent upon both idiosyncratic and contextual factors and affect the ways in which they alter their thinking and their practice” (p. 389). Flores’ statement supports our focus on PCK development of one ECT and the particularities of his context in this case study.

Like Cochran-Smith et al. (2012), we understand teaching as a social and cultural process, regarding “teaching as complex and interpretive, where individual agency interacts with the conditions of schooling and the cultures of schools in complex ways” (p. 849). School contexts, including changing geographic contexts, shape the development of ECTs in significant ways (Caudle & Moran, 2012; Flores & Day, 2006; Hoffman et al., 2005). The discourse of cultural relevance (Aylward, 2007; Ladson-Billings, 2014) informs this paper’s focus on teacher education that addresses the needs of ECTs in northern Indigenous communities.

Methods: A Case Study of one ECT’s Evolving Teaching Practice

This case study is part of an ongoing multi-year, longitudinal study of over 60 pre-service and early career teachers’ use of content area literacy strategies (Mitton-Kukner & Murray-Orr, 2014; Mitton-Kukner & Murray-Orr, 2015; Murray-Orr & Mitton-Kukner, 2015; Murray-Orr, Mitton-Kukner & Timmons, 2014). This research project has been granted ethics approval by the Research Ethics Board of St. Francis Xavier University. Don, the ECT who is the focus of this paper, began his teaching career in northern Canada in 2013 after graduating from a teacher education program in Atlantic Canada, and was still teaching there at the time of this paper’s completion in 2016. In this paper, we use a longitudinal single-case design (Yin, 2014) to investigate one ECT’s evolving practice from his final term in a B. Ed. program to the end of his second year of teaching.

Yin (2014) suggested five rationales for use of a single-case design such as the one on which this paper reports. One of these is the longitudinal case, and Yin describes how studying a longitudinal case relevant to one’s theoretical propositions can highlight “trends over an elongated period of time, following a developmental course of interest…[and can contribute to theory development about] how certain conditions and their underlying processes change over time” (p. 53). Don was a research participant in 2013, when he and 31 other PSTs were interviewed before and after his final practicum in April 2013 after completing the compulsory Literacy in the Content Areas course in the winter of 2013. In the spring of 2014, we invited 10 first-year teachers who were former PSTs in the B. Ed. program at our university and participants of this study in 2013, to do follow-up interviews about their experiences integrating literacy into their content area teaching.

Of the 10 people invited, five first-year teachers, including Don, agreed to take part and were interviewed between March and June 2014 by Skype and phone. As Don and others were teaching in locations far from the university from which they graduated, interviews could not be conducted face-to-face. Similarly, in the spring and summer of 2015, Don and the other four ECTs were interviewed as they completed their second year of teaching. In this case study, we explore how Don’s perspectives on infusion of literacies into his teaching shifted from his PST interviews on March 19 (21 minute interview) and April 29, 2013, (25 minute interview) drawing on transcripts from the first-year teacher interview on May 9, 2014, (65 minute interview) and in the second-year teacher interview on August 22, 2015, (66 minute interview) as well as emails, and work samples written by his students. We did not begin the larger research inquiry by expecting to write an in-depth case study of a beginning teacher in a remote Indigenous context, but close reading of the data over the two years in conversation with Don led us to believe there was something significant for the field of teacher education, particularly in how Don adapted to life in this school and community.

During the first phase of data analysis, we individually analyzed the four interview transcripts (Creswell, 2007; Merriam, 2009), noting recurring patterns that we each saw emerging within and across the interview transcripts. Following the individual process of open coding, we each clustered open codes into similar families of thought to create analytic codes (Merriam, 2009). The second stage of data analysis included several meetings where we met and noted the similarities amongst the analytic codes each of us had created. After discussing these codes, we returned to the interview transcripts and confirmed where we had enough data to support their inclusion in our portrayal of Don’s early years of teaching. To do so, we worked with elements of portraiture (Lawrence-Lightfoot, 1997) paying careful attention to how context informs and shapes the ways a researcher may interpret meaning. We shared drafts of the portrait with Don to create a further opportunity for his response and input. Don provided feedback on our interpretations and noted our efforts to showcase his voice throughout the portrayal. We acknowledge that a limitation of this study is its dependence on self-reporting through interviews, and recognize our portrait of Don is based upon his representation of reality. We did not conduct field observations, as it was not financially possible for us to visit the schools in which Don was located during his practicum in the B.Ed. program or later at his remote northern school. Additionally, this study does not integrate the views of Indigenous community members, students, or others. Further inquiry to find out from Indigenous peoples how they view the issues discussed here is imperative. With these limitations in mind, we endeavoured to document Don’s growth over time, as he adapted to life in a remote northern Indigenous community, particularly Don’s emphasis upon how his understanding of the school and the community intersected with his decisions regarding relationships with students, involvement in the school and broader community, as well as instructional decision-making in the classroom.

Findings: Don’s Reflections on Teaching: A Case of Evolving PCK Shaped by Context and Beliefs

In this section, we present our analysis of interviews with Don across two years: from the final term of his B. Ed in 2013 to the summer after his second year of teaching in 2015. In 2013, Don’s interview reveals a desire to enable students to develop traditional school-based literacies, particularly their writing. In both 2014 and 2015, Don spoke at length about his thinking about the school, the community, the students, and his teaching practice as he came to the ends of these school years. In 2015, he noted how he saw his practice had changed over time.

Don as a PST: Committed to incorporating literacies as part of instruction

With a graduate degree in history and qualified to teach social studies, music, and core French, Don was a PST who had reportedly high expectations for his students and felt his role in the classroom as a secondary teacher was to foster opportunities for students to show their learning. During his final teaching practicum in the spring of 2013, Don was at a small rural high school moving between several grades and subject areas and seemed to thrive in this environment. Don explained that while he attempted to do many different things with his students from role-plays to simulations, he consciously put a lot of emphasis on “time for writing…I really wanted to make it part of my practice to have students writing with me.” Don credited his interest in writing to his experiences in his prior teaching practicum where he was “shocked at the poor quality of [grade 9 students’] writing”, and noted the impact that knowledge of literacy strategies had made upon his planning. In particular, Don felt most successful making use of writing to learn strategies (Daniels, Zemelman, & Steineke, 2007) and noted the frequency with which he used reflective writes and writing breaks, both terms for strategies from the Daniels, Zemelman and Steineke book, which was the text used for the Literacy in the Content Areas course. He stated he used them “pretty much in every lesson.” Don emphasized the importance of creating opportunities for students to “write down what [they] were thinking” and observed that for some students, he felt his approach enabled their writing to become “a lot more coherent just over the course of 5 weeks.”

In comparison to his previous teaching practicums, Don identified a major difference about himself in that he felt:

More equipped to imbed literacy as a major part of my instruction where my first practicum I was more concerned with telling the students what they needed to learn…I quickly realized that that doesn’t work. I feel [that] when students are learning and they’re able to write about their learning, and express their success in learning through writing, it’s much more effective.

At the end of his B. Ed. studies, Don seemed aware of the importance of creating opportunities for students to show their learning through written texts and was looking forward to “increasing the variety of writing strategies that I use…to have them ready to use at all times.”

Don’s first year of teaching: Adapting to the particularities of a different teaching context while maintaining expectations

In contrast to Don’s growing confidence a year earlier regarding his use of literacy strategies, during an interview on May 9, 2014, Don evaluated his teaching practice at the end of his first year at a school in an Indigenous community in northern Canada quite differently. Balancing multiple responsibilities, which included teaching several subject areas in grade 7 (English, social studies, math, science, and computer), facilitating an after-school music program, coaching hockey on the weekends, and being a homeroom teacher, Don explained that in terms of infusing literacy he had not been “able to do as well as [he] had hoped.” Don attributed the instructional challenges he experienced to the complex needs of his students. Don explained that, with the exception of one student in his class, all had “a diagnosed learning disability” and that because of this he “had to learn to adjust,” and he found it challenging to meet all of their “needs at the same time.”

With a background in graduate studies in Canadian history with a focus on the racist policies affecting immigrants to Canada, Don seemed well-positioned to theoretically understand the community in which he was situated, as one where community members and families of students were attempting to “fight against colonization and maintain [their] cultural identity” after many years of governmental control of education and many other aspects of their lives. This control included the enforcement of racist and discriminatory policies (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015a), which resulted in, among other things, an inferior educational system in many (though not all) areas (Hare, 2011). During this long period of colonization in many communities, non-Indigenous teachers from the south had come and gone, leading students to be cautious about developing relationships with teachers who might leave at any time (Wotherspoon, 2006).

According to Don, such cautiousness existed in the community in which he began his teaching career, but things improved after the school holiday in December, once the students saw him and his partner “return to the community.” He felt he gained a small measure of students’ trust when they saw him return in January. He also described working hard at gaining students’ trust through involvement in their lives:

So, I’m quite busy after school with trying to get people playing music and using the equipment that’s here…in addition to that, I started playing hockey, so that’s more of a community event, but I’ve also started coaching hockey…so...on weekends, I coach a lot of the students in our school.

Don’s willingness to become active in after-school activities suggests he was aware of the importance of building relationships with students and the community, a decision which reportedly enabled him to spend more time with his students outside of school.

Although Don described his understanding of the effects of the community’s history upon schooling generally, Don noted significant issues in terms of the students he taught and his perceptions of their learning. In response to these challenges, Don was somewhat uncertain and decided to focus on reading comprehension because he felt students struggled to “get meaning from the words that they’re reading” and attempted to use vocabulary activities, brainstorming, and graphic organizers as a way for his students to demonstrate their understanding. Don noted that to assess student learning he began to rely upon “observations…and the way they interact with material orally” and that while he attempted to push “as hard as I can” to improve their reading, he was mindful to “back off” when he felt students were not responding. Looking ahead to his next year of teaching and his plans to return to the school, Don explained that his overall goals were to help students understand that learning was about the opportunity to learn from mistakes and to persevere with challenging tasks, “that mistakes are good, and it’s good to think things through, make a list, make a rough draft, correct it, make it better the second time you do it.” We note Don’s emphasis on the idea of learning from mistakes and acknowledge his efforts to determine what strategies were most useful for his students in terms of reading comprehension. The process he described seems to reflect an evolving PCK, as he identified a pedagogical approach that seemed to be appropriate for his students from the range of possibilities in his repertoire.

Considering Don’s PCK development in light of this interview conversation, it seems that despite the challenges he experienced, as he attempted to adjust to a new school and cultural environment, he continued to search for and implement ways to support student learning. We note Don moved away from his emphasis on writing as his primary assessment tool as described in his interview at the end of his B. Ed. program to the emphasis that he placed upon observing student learning through oral means. Don’s belief in having high learning expectations for his students, and his ability to use literacy strategies to actualize this belief, was a common theme carried forward from his B. Ed. in 2013 into the end of his first year of teaching in 2014. The pedagogical decisions Don made to support his students to achieve these expectations were refined given his growing awareness of the complexities of his students’ lives and the importance of using alternative ways to assess student learning. At the end of his first year, Don, and his partner, planned to return for a second year in the community and remained positive about his students’ futures.

I’m optimistic, and…I think a lot of what takes up my time here is adjusting, and trying to figure out how to teach students, and I’m really hoping that as other things become more settled, then I can better focus on…help[ing] these kids learn to read and write better.

Don’s second year of teaching: A greater understanding of context leads to PCK growth

During the conversation that took place after his second year of teaching in the same community in northern Canada, Don began with an animated description of how his after-school music program had grown and the students had performed in local and provincial festivals and events. Don reported how an organization from southern Canada wanted to support the after-school music program and that school administrative support had grown as well:

They gave us money to buy all new equipment for the secondary music program. And then we took students to another community for a talent show…I took a five-piece band and we won that talent show. It was so great and it was such a positive thing for the community. It just made more people interested in our program and learning music. So…we ended up playing at a big festival in our community, which was actually the top prize [for winning the talent show], to play in our community during the big [community] Snow Festival…. We took that same band to [a large Canadian city] and we played in [that large Canadian city] Folk Festival last June. There’s a YouTube video.

Don described how the students in his music program learned drumming, guitar, keyboard, and singing, and how some students were throat singers, a traditional Indigenous form of making music. While he also talked in detail about his teaching inside the classroom, Don felt his passion for music was inspiring his students to participate in the band program. Don did not use the phrase “musically literate” as he did in his 2013 interview; we note a subtle shift in Don’s discourse, particularly the emphasis he placed upon the benefits of the after-school program for the community as opposed to the individual benefit of musical literacy.

When asked about his use of literacy strategies and instructional decision-making in his teaching in his second year, Don wanted to note a change he saw between his first and second years of teaching: “I remember the interview I had with Jen and I do remember being quite negative at the time.” He recalled he found teaching in his first year “really challenging,” and remarked that at the time he was frustrated that he felt he was “not able to do very academic work with them.” Looking back from the vantage point at the end of his second year in the school, Don saw things a bit differently: “I think what I failed to identify when I spoke with Jen [in 2014] was that the majority of my literacy teaching was teaching critical literacy and I really just tried to have them understand the world around them.” In this moment, we note Don’s attempts to reconcile who he was in his first year of teaching with who he became in his second year. Implied in Don’s comments are his own concerns about the possibility that he unintentionally created a binary between academic literacy and cultural literacy in his first-year teaching practices; in a way reifying a deficit narrative about what Indigenous students bring to school. Don’s emphasis upon wanting his students to notice the world around them may also have been a comment upon himself in his first year, as he tried to navigate a new world far different from his upbringing.

During this 2015 interview, Don described how students brought their knowledge of what was happening in the community into the classroom, and how sometimes this included violent and tragic events such as murders or suicide:

These are just the types of things that we would talk about and…it may not have been…reading a book in English… But…we were talking about their lives. The lives of people in the community, the decisions that people have made in the community, the results of those decisions, and how things could have been different and how their lives could be different based on decisions they make.

Don’s description of his teaching shows the kinds of literacy practices he was intentionally choosing to foreground and suggests that these practices lived in connection with the relationships that he had fostered with his students. He reportedly used what was happening in the community as a text for students to think deeply about the meaning of those events for themselves. He realized students brought particular windows to these texts, and through discussion he tried to help them open up some different perspectives onto these events. Don noted that this kind of literacy endeavour required a kind of trust that takes time to build, and that by the end of his second year, “it [was] completely different…the way students interact with us [Don and his partner]. And the way they seem to enjoy the fact that we are around them and around the school it makes us feel really good coming back.” Don’s community involvement through music and hockey, among other activities, and his increased understanding of the context over the first two years of his teaching appeared to help him see what he was doing in his first year of teaching differently. Don in this conversation seemed to realize that although the work in which he engaged students was not what he originally anticipated upon arrival, the relationships he had fostered seemed to open up possibilities for learning to take place.

As part of this second interview, Don described a variety of professional resources made available to him, which seemed to support both his growth and the broadening of his teaching practices in the community and school. Don described major professional development initiatives that focused on educational topics specific to remote northern Indigenous communities:

We have workshops and we have opportunity to work with teachers who teach in the same sector as us in different communities. So I…visit[ed] other teachers that teach secondary social studies and English and we get to work together and talk about things that are successful in their schools and what students like and what they don’t like…. The topics that we are often working on in our workshops are often very North-specific.

Don reportedly benefited from having the opportunity to work with other experienced teachers and pedagogical consultants in the ways he learned how to better “understand the students” he was teaching. He also described the impact of a new principal at his school that year: “We have new administration this year in [the community], and so far there have been some positive changes.” We noted with interest how Don observed that not every teacher seemed to share his own investment in the school and its community. He commented,

Unfortunately, there still are teachers that come here and they don’t have the idea that they’re teaching the student. They have the idea that they’re teaching the material and it’s for the students to learn it or not…. It’s also the[se] teachers that aren’t involved with the students in after-school programs…they don’t really make an effort to become a part of the community.

In contrast to this scenario, Don seemed to welcome an increase in his classroom responsibilities his second year taking on the teaching of “the entire secondary sector in English and social studies,” from grades 7-12, with one grade 7-9 class and one grade 10-12 class of students. Don was enthusiastic about these changes in that having the higher grades enabled him “to do a bit more complex literacy work, but a lot of it was again contextualising the community…to better understand their community’s past, therefore understanding the present a bit more.” We are reminded of Don’s background in history with this statement, and also of his growing confidence in choosing both materials and pedagogical approaches in his classes:

It remains a critical literacy approach but now that I’ve got some higher-level students, I’m able to use a few more textual resources…but also geographical resources, and I guess it’s a multi-disciplinary approach to critical literacy. I need to find texts that are relevant to their lives.

Don’s choices of texts expanded in his second year of teaching, in part due to changes to his course assignment, with students in older grades. He also appeared to feel more capable to make decisions to use alternative texts. In the following statement, Don’s knowledge of his students appeared to be a factor in his instructional choices as well:

I have to really diversify the work that students are having to do and change my expectations from student to student…the literacy abilities that they are gaining from it are going to be different from person to person.

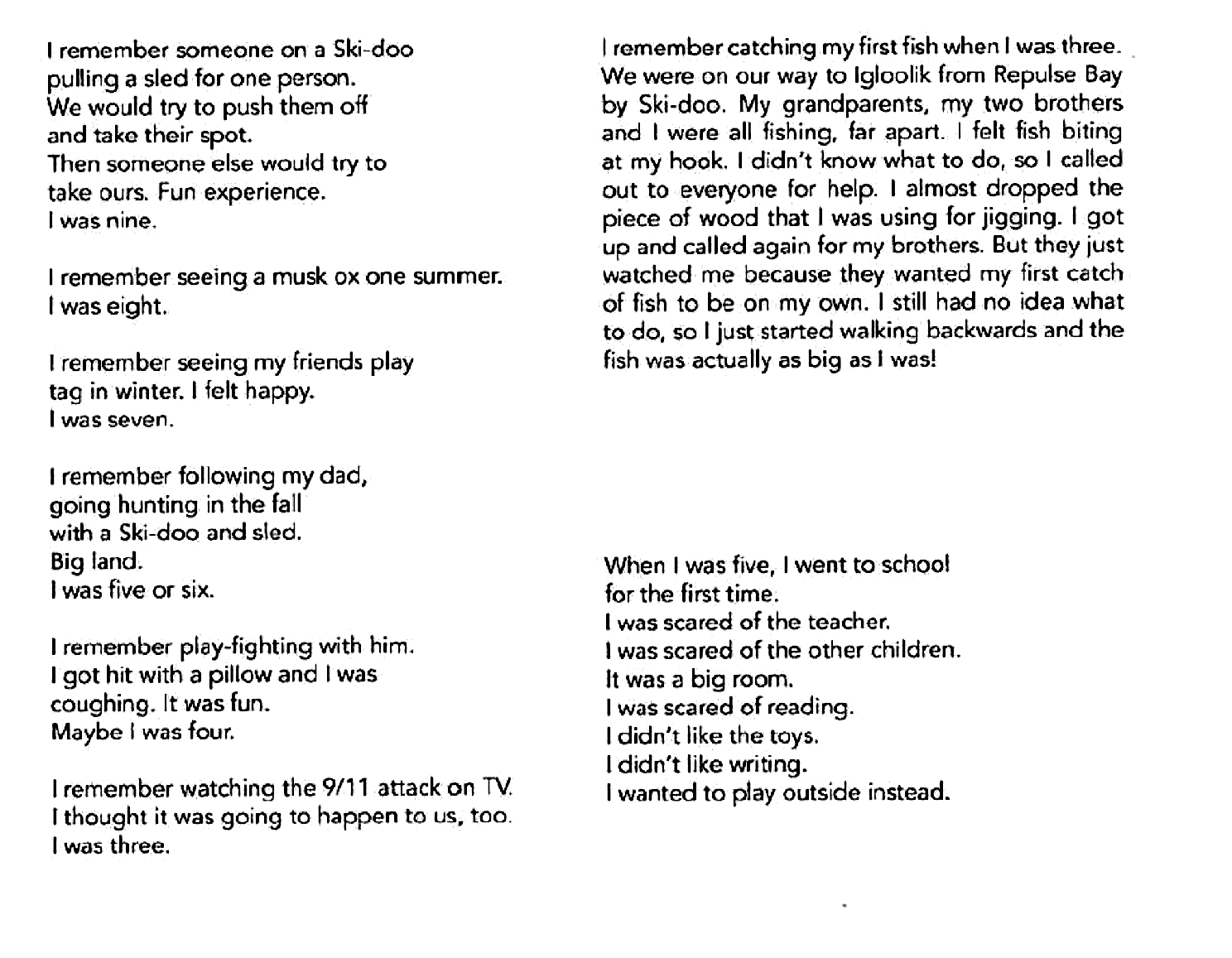

Differentiation seemed to be emerging in Don’s second year of teaching, as he made decisions about choices of texts and activities, nuancing them according to his perceptions of different students’ needs. The conversation about his changing thinking regarding materials, instructional methods, and the need to differentiate suggested Don’s PCK had been evolving in response to where he was situated. For example, Don provided a detailed example of a cross-curricular social studies / English language arts inquiry unit that he taught in his second year using primary source materials such as photographs and documents about an agreement that was signed with the provincial government by all Indigenous communities in the area except for his community. Not signing this agreement shaped the history of the community and the school.3 Don also incorporated recent tourism pamphlets that referred to the community’s decision not to sign, and he had students talk with Elders and family members in the community about their knowledge of this event. Don described the use of critical literacy practices in this unit, engaging students “to use the text and the photographs and their conversations with people in the community to…better understand why their community has not signed this agreement.” Don’s emphasis upon “using multiple ways of looking at something” suggests these were becoming increasingly part of his repertoire of teaching approaches, due to the need to differentiate but also because of the richer understanding he felt resulted from this approach. Three pieces written by Don’s students and published in a provincial school newsletter (Figure 1) illustrate the ways Don invited his students to write using literacy practices focused upon local and out-of-school literacy resources (Wiltse, 2015).

Figure 1. Three of Don’s students’ writing samples (students’ names removed)

Looking at Don’s perspective on his second year of teaching, he seemed quite intentional in his use of both traditional literacy practices like close reading and writing about experiences, as well as critical literacy practices including talking with community members, considering multiple perspectives, and thinking critically with students about how the community’s decision not to sign this agreement had shaped their lives. He described how his literacy goals had changed from his first to second year. In his first year, he “was really ambitious and eager to be very academic,” but over time he appeared to realize that academic goals devoid of the context of the school and community in which he lived were not such great goals after all. Don began basing his instructional decision-making on the students, both individually and as members of this particular community.

Discussion: Don’s evolving teaching practice in the context of his community and school

Three themes arose from our analysis of Don’s reports of his teaching from 2013-2015: Don’s shifting teacher identity as an ECT adapting to life in a northern Indigenous community, his evolving pedagogies, and how his experiences may inform our teacher education program and others.

Don’s teacher identity

Don completed his B. Ed. program in 2013 with specific ideas about how to support students in achieving success, such as a desire to focus on improving students’ writing, after being “shocked at the poor quality of [grade 9 students’] writing” during his pre-service teaching. In May 2014, as his first year as a teacher in a northern Indigenous community came to a close, Don described being disappointed with himself because in terms of infusing literacy he had not been “able to do as well as [he] had hoped.” It appeared there was a disconnection between his teaching practice as planned and the complexities of the classroom and school context in which he found himself. We noted the possibility of a binary emerging between academic literacy and cultural literacy in Don’s first year teaching practice. His disappointment with himself suggests he was unprepared for some of the struggles he encountered as an ECT in the Indigenous community in which he found himself. Despite Don’s reports of feeling inadequate, he provided examples of how he felt he was attempting to support student learning and he spoke of remaining optimistic that he would better understand how to successfully incorporate literacy practices into his teaching.

Barnatt et al. (2016) noted “the interplay between a teacher’s identity and agency was key” (p. 25). This interplay appeared to shape Don’s teacher identity. At the end of his second year, Don spoke more confidently about his experiences, and we saw in his account a return to the high expectations he had at the end of his B. Ed., albeit expectations that were shaped by his evolving teacher identity and growing awareness of the context of the community. He described his work with the after-school music program with much enthusiasm and told us about classroom activities that he felt were relevant and successful for his students. Don indicated that although his first year caused him to question his teaching approaches, he felt he was beginning to have more of a sense of who he was as a teacher in this context. In these ways, Don appeared to be moving toward an understanding of the purpose of education as broader than the promulgation of traditional school-based literacies, as including students’ lives outside of school as well.

Don’s evolving pedagogies

After the end of his second year of teaching in August 2015, Don described a number of teaching strategies he felt he was successfully putting into practice with his students. Don reported choosing relevant texts from students’ lives, such as local primary documents related to a significant event in the community’s history. Don also described purposefully enacting pedagogical approaches that drew on students’ context, and clear goals in his teaching practice. We are reminded of Aylward’s (2007) call to recognise place as a critical feature for curriculum planning. Shulman (1986) understood PCK as including “the most useful forms of representation of those ideas, the most powerful analogies, illustrations, examples, explanations, and demonstrations-in a word, the ways of representing and formulating the subject that make it comprehensible to others” (p. 9). Don’s decision to use texts that were part of the community’s past and present, and his pedagogical choice of critical literacy practices to explore those documents and oral stories, suggest a growing skillfulness in choosing and mediating appropriate forms of representation to enable students’ learning.

It appeared Don’s ability to discern the need for relevant texts and pedagogies in the classroom was shaped by his growing understanding of the community, its history, and people. The argument is made by McGregor (2015) that Nunavut teachers should have greater access to community histories, especially school histories, in order to better understand the communities they work in, build relationships, and decolonize schools. While Don was in a northern community outside of Nunavut, this argument is relevant to him. Wiltse (2015) suggested the importance of valuing the particular contexts and knowledge of students in northern Canada:

Awareness of the differences students bring to school is an important step; the next would be to recognize that these differences are not deficiencies, but funds of knowledge that can be utilised in teaching, in order for students to meet expectations (p. 66).

Don’s description of his teaching by the end of his second year suggests he endeavoured to honour his students’ funds of knowledge and infuse his teaching practice with lessons that focused upon and valued this knowledge. Don appeared to express a developing “social-political consciousness” (Aylward, 2007, p. 3) in pedagogical decisions such as choosing learning materials related to the community’s history in relation to colonizing forces. Some of the dispositions Berger (2007) described as necessary for teaching in Indigenous communities, such as “reflection, growth, [and] advocacy” (p. 1) seemed to emerge in Don’s discussion of his second year of teaching.

How can this case study of Don inform our teacher education program and others?

Don’s yearly conversations with us from 2013 to 2015 caused us to look at our teacher education program with fresh eyes and consider what recommendations we might offer. Those in other teacher education programs may see relevance in these recommendations as well. While Don’s high expectations for students were evident at the end of his B. Ed. program, and he was vocal in his awareness of the devastating impacts of colonization on Indigenous peoples in Canada and the need to redress the inequities faced by Indigenous communities, it is not clear that he was fully aware of some of the specific challenges he might encounter and how he might position himself as a new teacher in his new community. This suggests that while our teacher education program has had a clear focus on engaging PSTs in developing a “social-political consciousness” (Aylward, 2007, p. 3) and an equity lens, we must continue to improve our efforts to support PSTs to understand classroom and community contexts more explicitly. Burleigh’s (2016) call for the need to better prepare non-Indigenous teachers for the contexts of Indigenous schools and communities resonates with us. While we endeavour to provide field experiences that are tailored to the teaching contexts PSTs plan to seek out, we recognize that connections with and unpacking of those field experiences are significant. We work to place PSTs in Aboriginal community schools and schools with substantial Aboriginal populations, especially PSTs who plan to look for positions in Indigenous communities. Of course, there are many contextual differences across Indigenous communities and schools. Incorporating more reflection and discussion on field experiences, on pedagogical successes and challenges, on building relationships with students and families, and on emerging teacher identities are vital aspects of the B. Ed. program that could be improved. Such improvements could support PSTs to anticipate that each new community in which they teach will demand a process of learning about the people and place so that they can tailor their teaching to that context.

Don appeared to feel a sense of disequilibrium in his first year of teaching, seeming somewhat uncertain about his teacher identity. He worked to regain his equilibrium, choosing to live as an actively engaged community member through music and hockey, and choosing pedagogical approaches that showed his interest is the history and social context of his community. The importance of Don’s sense of agency to make decisions that helped him grow in his teaching practice and feel connected to his community point to the benefits of ensuring that PSTs gain at least some tools for developing a sense of agency in their school contexts. In addition to the development of a beginning repertoire of pedagogy, pedagogical tools, and content knowledge, attention to PSTs’ understanding of the importance of attending to new contexts is crucial, to providing a foundational understanding of what to expect and ways to negotiate in unfamiliar contexts.

In response to what we have learned alongside Don, we see how aspects of our teacher education program might be improved. While this paper is focused on one ECT, we are following others, and hope our analysis of the conversations we have with these ECTs will suggest other possible ways to renew our program. We suggest there may be value for other teacher education programs in inquiring into the experiences of some of their graduates, as a method of staying connected to the issues and challenges that new teachers face and how those can inform programming.

Conclusion

This paper used a case study approach to inquire into how one ECT refined his teaching practices as he made the transition from a B. Ed. program to his first two years of teaching of teaching in northern Canada, from 2013-2015. The development of Don’s PCK was traced from his high expectations and commitment to improving students’ writing at the end of his B. Ed., through his feelings of uncertainty near the end of his first year of teaching, as he struggled to get to know his students and adapt his teaching practice, challenging his PCK growth in the Indigenous community school context, to his growing sense of agency and evolving PCK and teacher identity in his second year of teaching.

Don described successes and challenges he encountered as he appeared to work toward developing a social-political consciousness, and an awareness of the community context and history that enabled him to make decisions that supported the learning of his students in a northern Indigenous community. Don’s recounting of his experiences was instructive for us as teacher educators, enabling us to see possible implications for our teacher education program.

Notes

- 1. Don’s name is a pseudonym.

- 2. In our context, the Bachelor of Education degree is a 2-year post-graduate program of study.

- 3. This unit of study is described somewhat generally to protect the confidentiality of the participant and his school.

References

Aylward, M. L. (2007). Discourses of cultural relevance in Nunavut schooling. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 22(7), 1-9.

Barnatt, J., Terrell, D. G., D’Souza, L. A., Jong, C., Cochran-Smith, M., Viesca, K. M., … Shakman, K. (2016). Interpreting early career trajectories. Educational Policy, 1-41. doi: 10.1177/0895904815625286

Battiste, M. (2002). Indigenous knowledge and pedagogy in First Nations education: A literature review with recommendations. Retrieved from: http://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education/24._2002_oct_marie_battiste_indigenousknowledgeandpedagogy_lit_review_for_min_working_group.pdf

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Vancouver, BC: Purich Publishing.

Beck, C., & Kosnick, C. (2014). Growing as a teacher: Goals and pathways of ongoing teacher learning. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense.

Berger, P. (2007). Some thoughts of Quallunaat teacher caring in Nunavut. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 4(2), 1-12.

Burleigh, D. (2016). Teacher attrition in a northern Ontario remote First Nation: A narrative re-storying. in education, 22(1), 77-90.

Caudle, L. A., & Moran, M. J. (2012). Changes in understandings of three teachers’ beliefs and practice across time: Moving from teacher preparation to in-service teaching. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 33(1), 38-53.

Cherubini, L., Hodson, J., Manley-Casimir, M., & Muir, C. (2010). ‘Closing the gap’ at the peril of widening the void: Implications of the Ontario Ministry of Education’s policy for Aboriginal education. Canadian Journal of Education, 33(2), 329-355.

Cochran-Smith, M., McQuillan, P., Mitchell, K., Terrell, D. G., Barnatt, J., D’Souza, L., & Gleeson, A. (2012). A longitudinal study of teaching practice and early career decisions: A cautionary tale. American Educational Research Journal, 49(5) 1-37. doi: 10.3102/0002831211431006

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Daniels, H., Zemelman, S., & Steineke, N. (2007). Content-area writing: Every teacher’s guide. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(3), 300-2314. doi: 10.1177/0022487105285962

Darling-Hammond, L. (2012). Powerful teacher education: Lessons from exemplary programs. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

DeAngelis, K. J., Wall, A. F., & Che, J. (2013). The impact of preservice preparation and early career support on novice teachers’ career intentions and decisions. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(4), 338-355. doi: 10.1177/0022487113488945

Flores, M. A. (2008). Mapping new teacher change: Findings from a two-year study. Teacher Development, 9(3), 389-412. doi.org/10.1080/13664530500200261

Flores, M. A., & Day, C. (2006). Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers’ identities: A multi-perspective study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22, 219-232.

Grossman, P. L., Valencia, S. W., Evans, K., Thompson, C., Martin, S., & Place, N. (2000). Transitions into teaching: Learning to teach writing in teacher education and beyond. Journal of Literacy Research, 32(4), 631-662.

Hare, J. (2011). ‘They tell a story and there’s meaning behind that story’: Indigenous knowledge and young indigenous children’s literacy learning. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 12(4), 1-26. doi: 10.1177/1468798411417378

Harper, H. (2000). “There is no way to prepare for this”: Teaching in First Nations schools in northern Ontario — Issues and Concerns. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 24(2), 144-157.

Hoffman, J. V., Roller, C., Maloch, B., Sailors, M., Duffy, G., Beretvas, S. N., & National Commission on Excellence in Elementary Teacher Preparation for Reading Instruction. (2005). Teachers’ preparation to teach reading and their experiences and practices in the first three years of teaching. The Elementary School Journal, 105(3), 267-287.

Jones, S., & Enriquez, G. (2009). Engaging the intellectual and the moral in critical literacy education: The four-year journeys of two teachers from teacher education to classroom practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(2), 145-168.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: A.k.a. the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74-84.

Lawrence-Lightfoot, S. (1997). The art and science of portraiture. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

McCormack, A., Gore, J., & Thomas, K. (2006). Early career teacher professional learning. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 95-113. doi: 10.1080/13598660500480282

McGregor, H. (2015). Listening for more (hi)stories from the Arctic’s dispersed and diverse educational past. Historical Studies in Education, 27(1), 19-39.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mitton-Kukner, J., & Murray-Orr, A. (2014). Making the invisible of learning visible: Pre-service teachers identify connections between the use of literacy strategies and their content area assessment practices. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 60(2), 403-419.

Mitton-Kukner, J., & Murray-Orr, A. (2015). Inquiring into pre-service content area teachers’ development of literacy practices and pedagogical content knowledge. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(5), 41-60.

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & González, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory into Practice, 31(2), 132-141.

Murray-Orr, A., & Mitton-Kukner, J. (2015). Fostering a creativity mindset in content area teachers through their use of literacy strategies. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 16, 69-79. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2015.02.003

Murray-Orr, A., Mitton-Kukner , J., & Timmons, D.J. (2014). Fostering literacy practices in secondary science and mathematics courses: Pre-service teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge. Language and Literacy, 16(1), 91-110.

Murray-Orr, A., & Tompkins, J. (2013). Implications of Aboriginal immersion for economic development, life-long learning, and community wellbeing. In D. Newhouse & J. Orr (Eds.), Aboriginal Knowledge for Economic Development (Vol. 1, pp. 98-104). Halifax, NS: Fernwood Press.

Olson, M. (2008). Valuing narrative authority, collaboration and diversity in revitalizing a teacher education program. In C. Craig & L. Deretchin (Eds.), Imagining a renaissance in teacher education (pp. 377-394). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015a). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Retrieved from http://www.myrobust.com/websites/trcinstitution/File/Reports/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015b). What we have learned: Principles of truth and reconciliation. Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Principles_2015_05_31_web_o.pdf

Wiltse, L. (2015). Not just ‘sunny days’: Aboriginal students connect out-of-school literacy resources with school literacy practices. Literacy, 40(2), 61-68.

Wood, M. B., Jilk, L. M., & Paine, L. W. (2012). Moving beyond sinking or swimming: Reconceptualizing the needs of beginning mathematics teachers. Teachers College Record, 114, 1-44.

Wotherspoon, T. (2006). Teachers’ work in Canadian aboriginal communities. Comparative Education Review, 50(4), 672-694.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.