The Struggle for Teacher Professionalism in a Mandated Literacy Curriculum

It was March and students had been in school for nearly seven full months. As a school board consultant, I1 was visiting a grade three classroom to touch base with the teacher about a student’s reading. Despite finding no increase in reading levels, the teacher was pleased with the student’s progress. I was pleased to hear that the student was doing well in terms of attitude, participation, and work completion, but the fact that he had not progressed from the reading level at which he had been assessed seven months ago was disturbing. When I probed deeper into the situation, the teacher shared with me that the boy’s level had not changed because he had not met the criteria for fluency as outlined in the relatively new reading program materials implemented by the school board. Fluency is one of four criteria by which students are to be assessed as readers, along with accuracy, vocabulary, and comprehension.

I was shocked by the restrictions, which the assessment procedures of the reading program seemed to impose, holding this child back from progressing to a higher reading level. The teacher, in accordance with the reading program manual, was evaluating the student based on the preset criteria for reading achievement. My concern was that this student had speech production issues, which inhibited his ability to speak fluently. Instead, he communicated orally in sentences which consisted of groups of two to three word phrases (ie., my dog… went outside…. and… and… he found a stick). The reading assessment required the child to read in a smooth and fluent manner, which he was physically incapable of doing. As a result, the teacher felt she was not able to record any change to his reading level in her evaluations, and therefore, it appeared there was no progress in his reading achievement. In this situation, although the child may have made significant advances in other aspects of his reading, the fluency requirement criterion represented a premise incompatible with the child’s speech production issue.

For quite some time I struggled to understand the teacher’s unwillingness to use her professional judgement regarding the child’s reading progress. I understood that the teacher was following the criteria outlined in the reading program, but at the same time I could not help but wonder why her professional decision-making did not override or, at the very least, cause her to question such strict and literal adherence to the program.

Description of the Research Problem within a Context

For the past three decades, national and state / provincial governments have developed educational policy to standardize literacy curriculum with the stated aim of increasing student literacy achievement (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, 2008; Dudley-Marling, 2005; Fullan, 2009; Lingard, 2010, 2011; Office for Standards in Education, 2002; United States Department of Education, 2002; Wyse & Opfer, 2010; Wyse & Torrance, 2009). The implementation of this policy has impacted both the literacy instructional practices of teachers and students’ classroom reading experiences in the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Australia, and Canadian provinces, all of whom have sought to develop a consistent approach to reading instruction that focuses on instructing and monitoring student reading achievement through the standardized testing of specific reading skills and strategies. While there are differences between the various governments’ approaches to policy, there is similarity in standardization, both in terms of curriculum and instruction.

In Canada, there is no federal involvement in public kindergarten through grade 12 education as policies are developed and legislated provincially (Fullan, 2009). From 1990 through 2003, there were four common educational aims pursued by Canadian provinces: standardization; shifts in the locus and direction of responsibility for education; requirements for measurement and reporting of achievement; and, the emergence of consequences linked to accountability reports (Jaafar & Anderson, 2007).

Prince Edward Island (PEI), the location of the study reviewed in this article, experienced significant changes to its educational system during the past five years. PEI is located in eastern Canada and is the smallest of 10 provinces. One of four Atlantic provinces, PEI is primarily an English-speaking province with a population of approximately 145,000 and 56 schools. In these 56 schools, there are both English and French Immersion classes. The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, commonly referred to as the Department of Education throughout PEI, is tasked with developing the curriculum, while it is the responsibility of the School Boards to deliver this curriculum to the school level.

Changes in senior administration in one of the two English school boards resulted in a shift in the focus and direction of the board. Literacy was the primary focus of the new administration, which was evidenced in addresses at local and provincial meetings, as well as within the literacy initiatives planned for 2011-2013 (Western School Board of Prince Edward Island [WES-PEI], 2011).

This concentrated focus on literacy achievement resulted in numerous new literacy initiatives, including the implementation of standardized instructional and assessment materials across the board, and the emphasis on consistency of program use, reporting, and evaluation (English Language School Board of Prince Edward Island, 2012; Kurial, 2005; Prince Edward Island Department of Education and Early Childhood Development [PEI-DEECD], 2012; WES-PEI, 2011). The programs and strategies implemented to address low literacy achievement scores were based on the work of Fountas and Pinnell (1996, 2007, 2008, 2009).

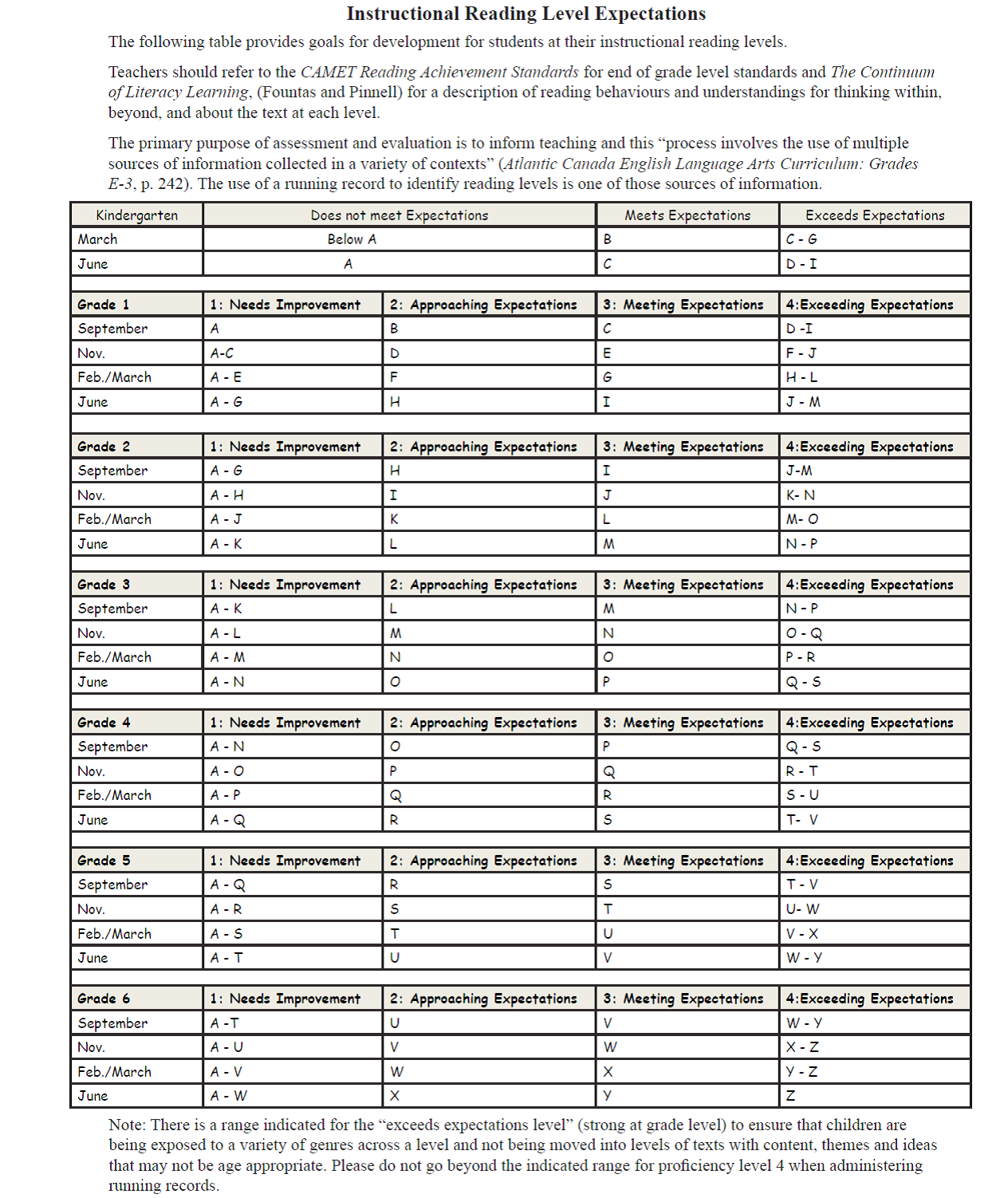

The Prince Edward Island Department of Education created a policy document called Guidelines for Running / Reading Record Assessment for Kindergarten to Grade 6 (PEI-DEECD, 2012). This document outlined how to conduct running records and how to assess an individual student’s oral reading. Despite Fountas and Pinnell’s (2007) caution that reading levels are to be used to support learners and not as an evaluative measure, the department-created document appears to represent a standardized approach to reading achievement and evaluation. The document outlined where students should be reading according to reporting periods and correlated with evaluative language — not meeting expectations, approaching expectations, meeting expectations, and exceeding expectations.

Within the PEI literacy initiatives, teachers were provided with program-specific training, and guidelines were established to monitor adherence to the programs through regularly scheduled grade-level meetings and routine reporting of student reading progress. Evaluative measures for reporting to school administration and school board officials were included as part of the program. This focus on evaluation and accountability is consistent with practices in other Canadian provinces including Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland (Campbell & Fullan, 2006; Government of Alberta, 2010; Government of Newfoundland, n.d.; Government of Nova Scotia, 2013; Government of Saskatchewan, 2012; Manitoba Government, n.d.; New Brunswick Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, 2013).

The increased focus on student achievement scores provided a relevant background to the events in my school board. Achievement scores are publically accessible and often permeate the media after their release. Pressure to improve scores is then felt across all levels — government, board, school, and classroom. As pressure mounts to increase achievement scores, so too does the publication of programs guaranteeing student achievement. Such programs are adopted by educational systems and infused into classrooms, often without sufficient analysis of their costs and benefits (Costello, 2012a, 2012b; Duffy & Hoffman, 1999; Herr, 1999; Spiegel, 1998).

This study explores how elementary language arts teachers make sense of literacy initiatives and investigates how teachers implement new programs and assessment practices in their classrooms. How teachers use their professional judgment in making decisions about the literacy initiatives that school boards require them to take up is also explored.

Research Questions

This study investigated the effect of instructional mandates on teacher professionalism in a climate of accountability and increasing standardization. As such, the concept of professionalism was explored and defined as it pertained to this study. The mandated curriculum was examined and the rationale behind the mandates was discussed. With a working definition of professionalism established and the mandates presented, it was then possible to examine whether the prescribed curriculum within the school board was having an effect on teacher professionalism. More specifically, my research question became “how were elementary language arts teachers making sense of the literacy initiatives which had been implemented in recent years?” and considered concerns related to teacher professionalism.

Theoretical Framework

The concept of teacher professionalism has evolved throughout the decades, with changes often reflecting trends in politics and society. In some of the literature, the term professionalism is used synonymously with the term professionalization. This interchangeability has created confusion about the meaning of professionalism as each of these terms has its own distinct meaning. This section explores this evolution, as it is important to develop an understanding of the issues and confusion surrounding the term professionalism.

It is important to understand that the concept of profession — the root of these terms — has been contested throughout history with no clear definition achieved (Evetts, 2006; Greenwood, 1957; Sciulli, 2005). Researchers have viewed the term profession as an occupation (Evetts, 2013; Hughes, 1958), while others avoid defining the term and instead “offer a list of relevant occupational groups” (Evetts, 2013, p. 4). Evetts (2013) defined the concept of profession as a “distinct and generic category of occupational work” (p. 4) but added that most researchers consider a profession to be the knowledge-based aspect of service occupations. Many academics have “debated whether teaching is a profession or a semi-profession, whether it is an art, a craft or a science” (Talbert & McLaughlin, 1996, p. 129). Despite the definition, or lack of definition, many researchers agree that the existence of a distinct knowledge base is the key aspect of a profession (Hargreaves, 2000; Hargreaves & Goodson, 1996; Helsby & McCulloch, 1996; Talbert & McLaughlin, 1996).

Professionalization, as discussed in the introduction to this section, is often erroneously used interchangeably with professionalism. In fact, professionalization is a related term which refers to the specific aspects of the status of teachers as professionals, including issues related to professionalization such as salary, status, and power (Evetts, 2013; Hargreaves, 2000).

Doyle (1986) defined a professional as “the master of a discipline and its interpreter” (p. 7). By this definition, mastery of knowledge and skill are considered integral to a profession, as is the ability to apply these in ways deemed appropriate by the professional. This definition lends itself to the inclusion of autonomy as one defining characteristic of a professional. Larson (1977) identified autonomy as a crucial criterion of professionalism, which helps to define it as other than common work.

Despite the dynamic nature of society’s views on professionalism, Hargreaves (2000) suggested some constants have emerged through which professionalism can be understood. These include “the quality of what [teachers] do; and the conduct, demeanour and standards which guide it” (p. 152). Within this definition of professionalism is embedded the idea of autonomy — teachers’ ability to make decisions about how to teach, based on their knowledge of subject and students.

Schön (1987) also referred to autonomy in his view of professional behavior as practical judgment. The work of Schön (1983) has been misrepresented by researchers who define professionalism in terms of institutional control. In Schön’s (1983) definition of professionalism as “a model of technical rationality” in which “professional activity consists of instrumental problem solving made rigorous by the application of scientific theory and technique” (p. 21), Abbott (1988) and Freidson (1994, 2001) focused on the idea of rigorous application of scientific technique as suggesting a routinized approach to professionalism. However, further exploration of Schön’s work reveals an emphasis on “instrumental problem solving” as being at the forefront of his definition. In his work, Schön referred to inferential reasoning and the ability of professionals to make individual decisions based on the uniqueness of the situation and the learned insights of the professional — aspects associated with autonomy, not routinization or institutionalization.

Teacher autonomy was a significant aspect in many definitions of professionalism, and issues related to teacher autonomy were noted throughout the literature in relation to prescribed curriculum. One such issue highlighted the restriction of teacher autonomy within the context of prescribed curriculum (Aoki, 1990). Aoki warned against situations in which “a curricular demand for sameness may diminish and extinguish the salience of the lived situation of people in classrooms and communities” and advocated for the need to “nurture the interpretive powers of teachers and students” (pp. 362-363). In this context, Aoki cautioned against the rigidity of a prescribed curriculum — a curriculum intended to promote consistency and sameness between and across classrooms and grades. Aoki’s work highlighted a concern among curriculum theorists that prescribed curriculum places the teacher in a subservient position to the curriculum, diminishing his/her autonomy (Apple, 1983; Bushnell, 2003; MacGillivray, Ardell, Curwen & Palma, 2004; Schwab, 1983).

Apple (1983) had concerns about what he termed the “tension” between a prescribed curriculum and teacher autonomy. Apple defined prescribed curriculum as being “less a locally planned program and more a series of commercial ‘systems’… [which] integrated diagnostic and achievement tests, teacher and student activities, and teaching materials” (p. 323). Although Apple identified strengths related to prescribed curricula such as more efficient planning, he also identified serious weaknesses associated with such externally controlled curriculum, including what he referred to as a “deskilling” of the teaching force.

Implementation fidelity is another aspect which contributes to teacher deskilling. Implementation fidelity refers to the degree to which a program is delivered as intended by program developers (Carroll et. al., 2007). Implementation fidelity also relates to the use of instructional strategies and the delivery of curricular content as it was planned (Los Angeles Unified School District; n.d.). While there is a range of views about how to evaluate program fidelity, at one end of the spectrum, the concept of implementation fidelity can suggest a scripted approach to teaching as evidenced in the following description:

Critical to the fidelity of the implementation of a curriculum is the importance of teaching the lessons in the order that the publisher has presented them. Teachers are also to teach each lesson according to the publisher’s recommended time. Furthermore, teachers are instructed to follow the recommendation of the publisher about how many lessons to teach per week. In addition, teachers are to make use of each publisher’s recommended questions and homework pages or activity sheets that will give students the opportunity to practice the skill they are learning. In brief, all of the publishers have specific recommendations for their programs that teachers should follow. (Los Angeles Unified School District, n.d.)

This view of implementation fidelity demonstrates a complete transfer of educational responsibility from teachers to curriculum developers. Rigid adherence to programs, practices, and resources eliminates the ability of the teacher to differentiate their instruction in ways they deem necessary to meet the needs of their students. In this context, teacher autonomy and decision-making become not only unnecessary but also undesirable, contributing to teacher deskilling and teachers’ feelings of decreased professionalism.

The notion of teacher deskilling and loss of teacher autonomy in relation to prescribed curriculum has been explored in various studies (Apple, 1995; Bushnell, 2003; Darling-Hammond, 1987; Goodman, Shannon, Freeman, & Murphy, 1988; Irvine & Larson, 2001; MacGillivray, Ardell, Curwen, & Palma, 2004; Pease-Alvarez & Samway, 2008; Pratte & Rury, 1988; Shannon, 1989, 1990, 2000; Shelton, 2005). Although the studies differ in size and methodology, recurring themes are identifiable throughout the literature — loss of autonomy, teacher identity, power and control, emotional impact, and resistance. Despite the different contexts and results of the studies, the influence of mandated programs on teachers is apparent and has ranged from significantly negative — teachers experiencing difficulty managing the literacy initiatives and feeling like failures, to significantly positive — teachers reworking their literacy program and incorporating the initiatives in a way that enhances their already established teaching styles and practices.

For the purpose of this study, professionalism will be defined as the ability of teachers to apply their content and pedagogical knowledge and expertise to solve problems and determine approaches suited to the needs of their students. This view of professionalism incorporates the acquisition and development of knowledge and skills, and also emphasizes the importance of teacher autonomy as an integral aspect of teacher professionalism.

Methodology

This study was based on a mixed methods approach to data collection and analysis. Creswell and Plano Clark (2007) described mixed methods research as an approach to inquiry which involves the use of qualitative and quantitative approaches “in tandem so that the overall strength of a study is greater than either qualitative or quantitative research” (as cited in Creswell, 2009, p. 4) and provides an expanded understanding of the phenomenon being examined. A mixed methods approach enabled us to consider questions of how many, as well as open-ended questions which explored individual teacher’s experiences. In relation to my research questions, I believed a mixed methods approach would enable me to gain more insight than I might through another approach.

Despite the advantages described above, McMillan and Wergin (2010) presented a healthy skepticism when they challenged the philosophical bases upon which mixed methods approaches are built. According to McMillan and Wergin, researchers subscribe to philosophical foundations more closely associated with either quantitative or qualitative research and as such, “while researchers may increasingly use mixed methods in their designs, with few exceptions they continue to operate from a dominant worldview” (p. 8). In light of this postulation, I believe it is important to identify my worldview as a researcher to better understand how my worldview might have influenced the lens I brought to my research study.

As a pragmatist, I was confident in my decision to have employed a mixed methods research approach by which I investigated my research question. “Pragmatism as a worldview arises out of actions, situations, and consequences rather than antecedent conditions” (Creswell, 2009, p. 10). Pragmatism focuses on the research problem and understanding the problem rather than on the methods employed to study the problem. As such, pragmatists are not committed to any one system of philosophy and are able to “draw liberally from both quantitative and qualitative assumptions when they engage in their research” (p. 10).

I was not worried about my worldview dominating my research as the pragmatic worldview lent itself seamlessly to the mixed methods approach. By having used a mixed methods approach to inquiry, incorporating both numerical and narrative methods of collecting, analyzing, and reporting data, I was able to provide the best understanding of my research problem.

Participant selection

Implementation of literacy initiatives in Prince Edward Island initially focused on elementary schools and as a result, elementary school teachers have experienced the effects of the implementation of the greatest number of literacy initiatives, along with the accountability and reporting that accompany these initiatives. Because of their experience and familiarity with the literacy initiatives, elementary language arts teachers were believed to be in the best position to reflect on these initiatives and the influence these policies have had and continue to have on both teaching experiences and decision-making. Therefore, elementary language arts teachers across my province were targeted for participation in this study. It is important to note that prior to beginning this study ethic approval was granted through the St. Francis Xavier REB (Research Ethics Board), as well as the school board ethics committee. Pseudonyms are used in the reporting of all data to protect the identity of the participants involved in this study.

Data collection: Surveys, interviews, and documents

For this study, I used surveys, interviews, and document analysis as methods of data collection. The first phase of data collection was the web-based teacher survey that was distributed to principals of 39 elementary and consolidated schools, which included 426 English elementary language arts teachers in grades 1 through 6. Of these 426 teachers, 71 completed the online survey. This represents a 17% rate of return on surveys. A low response rate can be considered a limitation of a study; however, it should be noted that online surveys receive lower response rates than other forms of surveys (Cook, Heath, & Thompson, 2000; Nulty, 2008; Ogier, 2005) and rates as low as 2% have been reported (Monroe & Adams, 2012). There is currently no definitive criterion outlining an acceptable response rate as this is dependent on both the context and the details of the survey and the study. It is important to note that the distribution group comprised 6% males while males make up 8.5% of the survey respondents, which suggests a fair gender representation of teachers in this board. Table 1 is a visual representation of gender and years of experience of respondents by both quantity and percentage.

Table 1. Survey respondent demographics: By quantity and percentage

|

Respondents |

0-5 years of experience |

5-10 years of experience |

10+ years of experience |

Total |

||||

|

# |

% |

# |

% |

# |

% |

# |

% |

|

|

Males |

2 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

6 |

6 |

8.5 |

|

Females |

14 |

20 |

13 |

18 |

37 |

52 |

64 |

90.1 |

|

Unknown |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1.4 |

|

Total |

16 |

23 |

13 |

18 |

42 |

59 |

71 |

100 |

By distributing a survey to all English elementary language arts teachers in the province, I was able to reach a larger audience and was therefore able to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how teachers across the province were making sense of the literacy initiatives. Surveys consisted of multiple choice and Likert scale questions, with the final question inviting additional insights through an open-ended comment section. Survey questions were piloted to ensure clarity. Four of my colleagues, all of whom had experience teaching within the literacy initiatives, read, responded to, and provided explicit feedback on the survey questions. The questions were then modified to reflect this feedback.

Once surveys were completed, I moved to the second phase of data collection: interviews. Survey respondents were provided the opportunity to volunteer for the interview portion of the study. I intended to use purposeful sampling (Merriam, 2014) to invite two teachers from upper elementary (grades 4-6) and two teachers from lower elementary (grades 1-3) as research participants to be interviewed. Within these pairs, I hoped to have teacher participants with significantly different years of teaching experience. Because of the low number of teachers who volunteered for the interview portion of my research, I did not need to group these participants according to years of experience (less than five years, more than five years) and setting (urban, rural) and then randomly select one participant from each, as I had initially planned. Instead all five teachers who volunteered were included.

Interview participants represented the same subgroup demographics as did the survey respondents. Participant demographics included teachers with:

- • varying years of experience (1 teacher with less than 5 years of experience, 3 in the middle of their career, and 1 very near to retirement),

- • varying grade level experience (2 with experience solely at the lower elementary level, 2 with experience in both the lower and upper elementary levels, and 1 with experience solely at the upper elementary level),

- • varying teaching experience (all participants had experience as classroom teachers, 2 had experience as resource teachers, and 2 had administrative experience),

- • various geographic and school demographics (1 from a French / English urban school, 1 from an English rural school, and 3 from dual-track rural schools).

This group of interview participants consisted of 3 males and 2 females who provided diverse perspectives, which fulfilled the criteria I had initially planned for.

I conducted two semi-structured interviews with each participant. The initial interviews were the main interviews and addressed questions and experiences related to my topic. The second interviews were shorter follow-up interviews to clarify anything from the transcript as well as to discuss revisions, additions, and/or deletions. The follow-up interview was essential in verifying that the information collected during the first interview and the interpretations of that data at that point in the analysis were true representations of the participants’ experiences. It also provided an opportunity to ask follow-up questions arising from the analysis of the transcripts. Such verification contributed to the validity and reliability of my study.

Interview questions included general demographics, challenges and successes related to the literacy initiatives, and questions exploring the experiences of teachers in relation to the literacy initiatives currently in place in my province. These questions were trialed in a pilot interview to identify areas of potential confusion or discomfort for participants. Although these questions were re-worked based on this pilot experience, I remained cognizant that each participant in my study would interpret and respond differently based on their own personal context. As a result of this knowledge, I allowed participants the time to process the question(s) and seek clarity if needed. I was mindful to prompt gently and remained conscious of the comfort level of my participants by paying close attention not only to their responses, but also to other cues including pitch, voice intonation, body language, eye contact, etc. I conducted interviews on the basis that the more comfortable participants were, the more successful the interviews would be.

Through interviewing participants, I learned more details about their experiences with the literacy initiatives and the curricular materials implemented to support the initiatives. I explored the influence these initiatives and materials have had on their teaching to better understand how teaching decisions were made within this context. A semi-structured interview design was chosen to allow participants to respond to questions while at the same time encouraging conversations that would enable participants to reflect on issues not directly contained within the interview questions. A printed copy of the interview questions was provided to participants at the start of the interview. Participants were informed that the questions were to be used as a guide and that both questions and responses may deviate from the guide depending on the nature of the conversation.

The third phase of data collection was the gathering of documentary artifacts. The most commonly used documents which outlined the implementation of literacy initiatives for language arts teachers included the School Board’s strategic plan, and a running / reading record policy document for the classroom; therefor these two documents were collected. Other supporting documentation included excerpts from program manuals, and documentation around assessment and evaluation of reading.

Data analysis

Data analysis was completed on an ongoing basis and began with the completion of the teacher surveys. Survey results were coded for identification of themes and patterns. Results were examined as a whole and then examined in terms of gender, years of experience, grade level, etc. to identify any patterns resulting from teacher demographics.

Data were coded to assist in the identification and analysis of themes. Survey responses were color coded according to rating (i.e. neutral responses were colored pink, negative responses were colored yellow, and positive responses were left uncoloured) and then themes were identified in relation to the questions. Interview transcripts were coded (Merriam, 2014) in terms of concepts or ideas expressed in the various questions (i.e. emotional responses — frustration, unsure, compliance, etc.; characteristics described in “ideal teacher”; challenges noted, etc.) and were compared and contrasted with themes from the literature.

This initial coding system followed Merriam’s (2014) definition of open coding as all ideas were considered. As I compared the open codes within and across surveys and interviews, I constructed categories by grouping codes which went together and which related with the concepts central to this study, including but not limited to teacher professionalism, loss of autonomy, issues of teacher identity, power and control, emotional impact, and resistance. Other themes which became apparent as I read through the survey results and interview transcripts were also considered. Merriam (2014) referred to this process as analytical coding due to the interpretive and reflective nature of the comparisons. I then explored these categories in relation to my research question as well as my theoretical framework and relevant literature and positioned my results within this context.

A large portion of my data analysis occurred between the initial and follow-up interviews (April and May 2014) and was verified through the sharing of the interview transcripts in the follow-up interview (May, 2014). Revisions and new information gathered during the follow-up interviews were analyzed in relation to the categories created and, when necessary, new codes and categories were created and initial data were re-analyzed in consideration of these.

Documents gathered during the data collection phase were read to gain a comprehensive understanding of the implementation of literacy initiatives as well as to explore connections to the themes identified from the literature surrounding teacher professionalism and those that emerged from the teacher surveys and teacher interviews. Analysis of this documentation provided rich sources of information, which, when used in combination with participant surveys and interviews, allowed for a deeper understanding of the classroom context as well as of the variables influencing teachers’ experiences and sense-making.

Outcomes and Key Findings

Teacher professionalism, intensification, emotional impact, and resistance were all themes that emerged from the data collected during this study. These are all issues associated with mandated programming (Apple, 1983; Bushnell, 2003; Irvine & Larson, 2001; MacGillivray, Ardell, Curwen & Palma, 2004; Pease-Alvarez & Samway, 2008; Shelton, 2005). This article focuses on teacher professionalism in relation to the educational context in PEI and shares implications and recommendations for addressing this issue.

Overall, responses to questions about professionalism were optimistic. Respondents reported strong agreement with the statement that they had opportunities to participate in purposeful professional learning opportunities, usefulness of classroom materials, and new understandings about assessment practices. The question related to professional learning opportunities had the highest mean (M) score of all questions related to professionalism, as 77% of respondents recorded a positive score (4 or 5) on the Likert scale. As indicated in Table 2, average responses for all demographic subgroups were over 4 and only two respondents recorded a score lower than 3 for this question. Responses to each question about professionalism were analyzed by subgroup to provide a comprehensive depiction of the data. As this article focuses on professionalism, only questions related to teacher professionalism were included.

Table 2. Survey question: Purposeful professional learning opportunities

|

To what degree do you participate in purposeful professional learning opportunities? |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

M |

|

All respondents |

0 |

2 |

14 |

34 |

20 |

4.02 |

|

Males |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

1 |

4.17 |

|

Females |

0 |

2 |

13 |

29 |

19 |

4.03 |

|

Teachers with 0-5 years of experience |

0 |

0 |

4 |

6 |

5 |

4.07 |

|

Teachers with 5-10 years of experience |

0 |

0 |

1 |

10 |

2 |

4.08 |

|

Teachers with 10+ years of experience |

0 |

2 |

9 |

18 |

13 |

4.00 |

The pedagogical beliefs of teachers were considered in the survey via a question asking teachers to what extent the literacy initiatives conflicted with their personal pedagogy (see Table 3). Responses to this question indicated minimal conflicts with an overall mean score of 1.82. All respondent subgroups averaged scores less than 2 with the exception of the subgroup of males. On average, males were very close to the “sometimes” (3) rating on the Likert scale. Although a 3 on the Likert scale can be considered to be a neutral response, it is still interesting that males scored significantly2 more negative than did any other subgroup. Table 3 provides a summary of these results.

Table 3. Survey question: Literacy initiatives and personal pedagogy

|

To what degree do the literacy initiatives conflict with your personal pedagogy? |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

M |

|

All respondents |

31 |

22 |

13 |

3 |

0 |

1.82 |

|

Males |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

2.67 |

|

Females |

29 |

20 |

11 |

2 |

0 |

1.77 |

|

Teachers with 0-5 years of experience |

7 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1.53 |

|

Teachers with 5-10 years of experience |

7 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1.69 |

|

Teachers with 10+ years of experience |

17 |

14 |

8 |

3 |

0 |

1.93 |

Probably most integral to my definition of professionalism was the question which asked respondents to identify the degree to which they feel empowered as professionals (see Table 4). Upon initial analysis, responses to this question were not concerning, with only 10 responses occurring in the negative range of the Likert scale (1 and 2). However, when further investigating this data, the number of neutral responses was concerning. Generally, neutral responses do not represent an extremity of thought, opinion, or attitude. However, for me, neutral responses to feelings of empowerment require attention as empowerment is an important part of teacher professionalism and teacher identity.

A total of 31 neutral responses were recorded for this question. This represents almost half (44%) of the respondents. When considered in light of all responses for this question, the mean response was 3.36, which again represented a neutral stance. This overwhelming neutrality toward empowerment is concerning as it suggests that teachers may feel as much disempowered as they do empowered.

Further analysis of responses to this question by demographics revealed interesting patterns in the data. One interesting finding indicates that teachers with 0-5 years of experience tend to feel more empowered than do teachers with more years of experience, while responses from teachers with 5-10 years of experience were below average compared to the group mean. Also interesting to note is that male respondents tend to feel slightly more empowered than female respondents. Another notable aspect of the data is that the only respondent to respond “not at all” to feeling empowered as a professional belonged to the group of teachers with more than ten years of experience and did not identify gender. A summary of these findings are represented in Table 4.

Table 4. Survey question: Professional empowerment

|

To what degree do you feel empowered as a professional? |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

M |

|

All respondents |

1 |

9 |

31 |

22 |

7 |

3.36 |

|

Males |

0 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

3.67 |

|

Females |

0 |

10 |

28 |

18 |

7 |

3.35 |

|

Teachers with 0-5 years of experience |

0 |

1 |

10 |

4 |

0 |

4.53 |

|

Teachers with 5-10 years of experience |

0 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

1 |

3.23 |

|

Teachers with 10+ years of experience |

1 |

5 |

16 |

14 |

6 |

3.45 |

Overall survey data displayed positive responses to many aspects of professionalism including opportunities to participate in purposeful professional learning opportunities. Responses to professional empowerment, however, indicated an attitude of neutrality, which may reflect less positive feelings regarding empowerment on the part of survey respondents. In the following section interviews are analyzed to determine similarities and differences with the survey data.

Interview data

Interview responses were critical in gaining a deeper insight into the teachers’ feelings of empowerment. All interview participants expressed feelings of loss of power and control, which suggest a sense of disempowerment. One participant reported feelings of disempowerment related to the literacy initiatives as illustrated in the following transcript excerpt:

I think the power and control one is hard for teachers because a lot of these initiatives you feel like they’re coming [from] top down. Even principals, I think, feel they’re [initiatives] coming [from] top down and maybe aren’t always suited for what’s going on in the building. I think teachers are feeling that too. And not that some of these initiatives are bad, or aren’t good, but I think when you feel like it’s being done to you instead of done with you then teachers have that feeling of loss of power and control. (Emily, excerpt from teacher interview, May 7, 2014).

In this excerpt, Emily, who has experience as both a teacher and an administrator, described the tensions created when programs and practices are implemented in a top-down approach. She made the connection between hierarchical decision-making and a loss of power and control at the school level. By making the contrast between perceiving things as done to you instead of with you, she illustrated how a lack of partnership in decision-making results in this loss of power and control. Another participant also made this connection, as evidenced in his statement that “more teacher input would give us a better sense of that — power and control — if we had more say in what we’re doing” (Leroy, excerpt from teacher interview, May 15, 2014).

William, a teacher and administrator, referenced power and control in terms of the environment he hoped to foster in his school. In his view:

I hope they [teachers] would feel that I would foster autonomy and teacher identity and would be anti power and control [over teachers]. I would hope that’s what they would think I would foster, all the while still delivering a quality curriculum. I think teachers here would feel free to do that but knowing that it has to be of quality — it has to be for kids. Because for me, that’s what’s most important. Are all schools like that? I hope so but I don’t think so. (William, excerpt from teacher interview, May 15, 2014).

In this excerpt William shared not only his beliefs about power and control, but also his vision for a positive teaching environment. He stressed his belief in the importance of teachers maintaining power and control over their lessons. He made the point that high quality education is an attainable goal while teachers exercise power and control over their lessons.

These transcript excerpts illustrate the participants’ understanding of issues of power and control as having an impact in school and classroom decisions. Lack of input by teachers, as suggested by interview participants, results in a loss of power and control felt by teachers and contributes to what Apple (1983) referred to as deskilling. While it is not clear how severe this sense of disempowerment is for these teachers, the literature reminds us that there can be significant impacts on professionalism. According to Apple, when teachers no longer plan or control their own work, they lose the skills necessary to do so, thus becoming deskilled. This loss of skills results in decreased teacher professionalism since skills and expertise are essential components of professionalism. Lack of input into decisions around classroom materials and other decisions also results in decreased professionalism as professional discretion, judgement, and decision-making are all central to professionalism. When curricular decisions are made externally, teachers’ decision-making is influenced. This shift in power and control may result in a loss of teachers’ professionalism.

One teacher referred to an overly scripted program as responsible for the loss of autonomy she perceives in her teaching. Similarly, when asked how the literacy initiatives influence teacher practice, another teacher responded by saying “they direct your teaching practice very heavily.” When probed further this participant responded:

Because it’s required of you. You may not see the benefit in everything — like the running records, the formal running records that needed to be submitted to the board. I don’t see a whole lot of benefit in that…I knew where they [students] were at so I could have told whoever at that point where the kids were at without having to do it [formal running records]. And I think most teachers are on top of where their kids, where their students are at that point in the year and just the time wasn’t worth telling me what I already knew. (Emily, excerpt from teacher interview, May 7, 2014).

Emily notes her frustration with having to conduct running records three times a year. She discusses feeling competent to evaluate and report on student progress without having to take the time to complete a formal running record. In this excerpt, Emily describes her perception of a tension between her professional decision-making and mandated practices. This feeling of losing autonomy to program adherence was echoed in another participant’s early teaching experiences when asked about how the literacy initiatives influence teaching practice. This participant, with over 10 years of experience, responded by saying: “for now we’re using what they give us.” When probed deeper, the participant responded:

when I was younger I felt like it [program] was the bible and I had…whatever they gave me…that’s all I had and I just didn’t know to go outside that realm and realize that it’s just one tool in, you know, your tool belt. (Leroy, excerpt from teacher interview, May 15, 2014).

Further investigation into this participant’s experience revealed the origin of this perception:

It was said that by omission, “here’s what you use.” So nobody said there was other stuff. They didn’t say there was, they didn’t say there wasn’t, but they just said it by saying “this is what you have” so…when you’re young, you don’t know the right questions to ask sometimes. (Leroy, excerpt from teacher interview, May 15, 2014).

The participants’ experiences highlighted in this section reveal a common perception of top-down control over curriculum and instruction. The comment regarding a fear of losing the autonomy to teach in ways that are valued by the teacher suggests the need to attend to the link between teachers’ professional values and teaching practices. When teachers experience a disconnect between what they are doing and what they want to be doing, they describe feelings of being disenfranchised and disempowered. Such feelings may contribute to a passive attitude toward professionalism as observed in the neutrality of responses in the teacher survey.

Despite some evidence of the negative implications of teacher deskilling and loss of autonomy, it is important and encouraging to recall that only 4% of survey respondents reported conflicts between personal pedagogy and current initiatives. It is also encouraging to note that while interview participants reported a loss of power and control and decreasing autonomy, positive comments were also shared regarding current initiatives including the benefits of guided reading (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996) and running records (Clay, 2000). Other literacy materials which interview participants reported as having a positive influence on their teaching practices included Moving Up with Literacy Place (Scholastic, 2007) and Daily 5 (Boushey & Moser, 2006).

Documents

Many programs and practices in my school board originated from the work of Fountas and Pinnell (1996, 2007, 2008). Because many of these programs and practices are implemented and supported through the Department of Education, they represent the school board’s interpretation of the original work, as is explained next. A good example of this would be the use of running records, which were created by Clay (2000), interpreted by Fountas and Pinnell (1996), and further interpreted by the Department of Education (PEI-DEECD, 2012). In effect, this results in a third generation interpretation of Marie Clay’s work. When information is re-interpreted, it sometimes becomes obscured.

One example of such obscurity occurred with using reading levels for assessment purposes. Fountas and Pinnell (1996) — in alignment with Clay (2000), who was responsible for the creation of the current process for oral reading records, also called running records — referred to reading levels as a means of informing instruction and decision-making in the classroom. In their conceptualization, reading levels were for instructional purposes only and were not intended to be formal evaluations. In the Department’s interpretation, the range of acceptability for each grade level is narrowed and reading levels correlate with reporting periods. This representation of reading levels indicates a more formal summative evaluation of student reading progress than the work of Fountas and Pinnell (1996). This use of running records represents assessment of learning and not assessment for learning. This indicates a shift from a focus on running records as an instructional tool to a narrowly evaluative tool, which contradicts the foundation upon which running records were developed.

Note. This figure illustrates the acceptable range of reading levels for each reporting period for grades Kindergarten through Grade 6.

Figure 1. Instructional reading level expectations (Source: PEI-DEECD, 2012, p. 19)

When the language within the running record guideline (PEI-DE, 2012) was analyzed, there were many words and phrases identified which suggested teacher autonomy is encouraged. Such phrases include: “to inform teaching” (p. 3, 12, 16, 19, 20), “to inform and plan instruction” (p. 4), and “guide instruction” (p. 12, 15). The role of the teacher is also defined in the guideline and includes the criterion that “teachers need to design and teach lessons” (p. 5). This reference to teachers being in control of the design and implementation of their lessons suggests an acceptance and expectation of teacher autonomy. The guideline also encourages teachers to refer to the Council of Atlantic Ministers of Education’s Reading Achievement Standards (New Brunswick Department of Education, 2008), which suggests the encouragement of teachers to go beyond the guidelines for planning and support. However this is not what was encouraged in practice.

As well as the conflicting information among the guideline (PEI-DE, 2012), the reading expectations chart (PEI-DE, 2012, p. 19), and the intentions of Fountas and Pinnell (1996) and Clay (2000) involving assessment for learning and the concept of the teacher as expert, there is a further apparent division between teacher perceptions of loss of autonomy and the promotion of autonomy within the guideline.

Document analysis revealed inconsistencies in the expectations around the role of the teacher as well as the purpose and use of assessment practices. Although teachers are positioned as experts in foundational documents and documents created by the Department of Education, the mandating of certain practices and programs seemed to contradict this positioning. Similar contradictions surfaced around the intended use of running records. Running records were created as a means of assessing learning in the classroom — to inform learning and teaching (Clay, 2000). The use of running records in my school board has been translated into an evaluative practice in which reading levels are determined to measure and report progress. Such inconsistencies may have an effect on teachers’ perceptions of their roles and identities within the classroom.

Discussion

While the context of my school board is not this extreme, feelings of decreased professionalism were reported by teachers who participated in my study. These feelings were described in relation to the literacy initiatives mandated by the school board and examples of restricted decision-making related to instructional time, materials, and resources were shared as specific examples. Teachers reported benefits of the initiatives despite their noted concerns regarding the implementation of the initiatives. This dichotomy — positive attitudes about what they are doing but concerns related to how they were asked to do it — are indicative of concerns with implementation fidelity. The intended purpose behind implementation fidelity is to ensure that programs and practices achieve the results promised by the developers.

In current school systems, this mindset of teacher as professional does not seem to be foremost. Rather, a mindset of accountability appears to dominate (MacNeill, 2014). Hibbert and Iannacci (2005) suggested that “increased pressures on school boards, administrators, and teachers to adhere rigidly to the management and measurements of standardized curricula and testing” (p. 716) results in the degradation of formal education to a system of reporting and accountability whereby goals are measured and determined by specific output. Hargreaves (2000) warned that such a subjugation of public education results in the de-professionalism of teachers; a situation he described wherein “professionalism is diminished…by subjecting [teachers] to the detailed measurement and control of narrowly conceived competence frameworks” (p. 167).

Professionalism was a major theme that emerged from my research study. In many survey questions about professionalism, teachers selected a neutral response and in interviews, all five of the participants reported what may be seen as passive attitudes toward their professionalism. In this context, professional passivity appeared to be a recurrent response by teachers to their circumstances. The surveys and interviews included examples of teachers’ descriptions of feeling they must teach or assess in ways that conflict with their values, or perceiving that literacy initiatives are being done to them as opposed to with them. Again teachers responded to these feelings in a passive manner. Such passivity may be the result of teachers’ perceptions of being positioned as subservient to the curriculum, affecting teachers’ identities as professionals and diminishing professional autonomy. Subservience results when teachers feel decisions are outside of their control (Aoki, 1990; Apple, 1983; Bushnell, 2003; Schwab, 1983).

Conclusion

This study provided me with the opportunity to better understand how teachers navigate the literacy initiatives implemented in their schools and classrooms. Through this study, I came to realize the numerous ways in which teachers respond to increased instructional demands, and the effect of these responses on their feelings of professionalism. The teachers in this study demonstrated a strong commitment to teaching and to meeting the needs of their students, an attitude which is to be commended and applauded. When teachers exercise their decision making power, based on their experience and expertise, to meet the needs of their students, they individualize and potentially improve the teaching and learning which occurs in their classrooms.

Findings from this study reveal issues of intensification, professionalism, emotional impact, and teacher resistance related to literacy initiatives being implemented in my province. Further study is recommended to explore these themes in more detail in order to improve how professional learning may be facilitated. Further research could also investigate differences in process fidelity and purpose fidelity and the effects of each on teacher professionalism, emotional impact, and intensification. Future research that examines the perceptions of school board personnel, in how they view teachers and to investigate their beliefs about the role of teachers as decision-makers, could provide additional insight into how decisions about new initiatives are made at the board level and are introduced into schools. Changes in this area would be influential in shaping how teachers experience these initiatives.

NOTES

- 1. The research study that led to this article was conducted by the first author. The second author assisted with the development of the manuscript but did not take part in the research itself; hence, all first-person pronouns refer to the first author throughout the text.

- 2. Significance in this context was determined using the N-1 Two Proportion test for comparing independent proportions of small and large sample sizes.

References

Abbott, A. (1988). The systems of professions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Aoki, T. (1990). Inspiriting the curriculum. The ATA Magazine, 37-42.

Apple, M. W. (1983). Curriculum in the year 2000: Tensions and possibilities. The Phi Delta Kappan, 64(5), 321-326.

Apple, M. W. (1995). Education and power. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2008). 2008 NAPLAN National Report. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu.au/verve/_resources/2ndStageNationalReport_18Dec_v2.pdf

Boushey, G., & Moser, J. (2006). The daily 5. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Bushnell, M. (2003). Teachers in the schoolhouse: Panopticon complicity and resistance. Education and Urban Society, 35(3), 251-272.

Campbell, C., & Fullan, M. (2006). Unlocking potential for learning: Effective district-wide strategies to raise student achievement in literacy and numeracy. Retrieved from http://edu.gov.on.ca/eng/literacynumeracy/inspire/research/ProjectReport_full.pdf

Carroll, C., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Booth, A., Rick, J., & Balain, S. (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Science, 2(40), 1-9.

Clay, M. M. (2000). Running records. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Cook, C., Heath, F., & Thompson, R. L. (2000). A meta-analysis of response rates in web or internet-based surveys. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60(6), 821-836.

Costello, D. (2012a). The impact of a school’s literacy program on a primary classroom. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue canadienne de L’éducation, 35(1), 69-81. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/canajeducrevucan.35.1.69

Costello, D. (2012b). Why am I teaching this? Investigating the tension between mandated curriculum and teacher autonomy. The Canadian Journal of Action Research, 13(2), 51-59.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1987). Schools for tomorrow’s teachers. The Teachers College Record, 88(3), 354-358.

Doyle, D. P. (1986, March). Teacher choice: Does it have a future? Paper prepared for the Task Force on Teaching as a Profession, Carnegie Forum on Education and the Economy, Hyattsville, MD.

Dudley-Marling, C. (2005). Disrespecting teachers: Troubling developments in reading instruction. English Education, 37(4), 272-279.

Duffy, G., & Hoffman, J. V. (1999). In pursuit of an illusion: The flawed search for a perfect method. The Reading Teacher, 53, 10-16.

English Language School Board of Prince Edward Island. (2012). English Language School Board Strategic Plan. Retrieved from http://www.gov.pe.ca/edu/elsb/files/2013/02/elsb_strategic_plan.pdf

Evetts, J. (2006). Short note: The sociology of professional groups: New directions. Current Sociology, 54(1), 133-143.

Evetts, J. (2013). Professionalism: Value and ideology. Current Sociology. 61(5-6), 778-796.

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (1996). Guided reading: Good first teaching for all children. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (2007). The continuum of literacy learning: A guide to teaching. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (2008). Benchmark assessment system. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (2009). Leveled literacy intervention. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Freidson, E. (1994). Professionalism reborn. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity.

Freidson, E. (2001). Professionalism: The third logic. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity.

Fullan, M. (2009). Large-scale reform comes of age. Journal of Educational Change, 10(2-3), 101-113.

Goodman, K., Shannon, P., Freeman, Y., & Murphy, S. (1988). Report card on basal readers. Katonah, NY: Richard C. Owen.

Government of Alberta. (2010). Literacy first: A plan for action. Retrieved from https://education.alberta.ca/media/1626397/literacyfirst.pdf

Government of Newfoundland. (n.d.). The roles of instructional resource and classroom / subject teachers in inclusive schools. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov.nl.ca/edu/forms/studentsupport/teacherroles.pdf

Government of Nova Scotia. (2013). Education and early childhood development: About PLANS. Retrieved from http://plans.ednet.ns.ca/about-plans

Government of Saskatchewan. (2012). Reading improvement instruction. Retrieved from http://www.publications.gov.sk.ca/details.cfm?p=76813

Greenwood, E. (1957). The attributes of a profession. Social Work, 2, 44-55.

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Four ages of professionalism and professional learning. Teachers and teaching: Theory and practice, 6(2), 151-182.

Hargreaves, A., & Goodson, I. (1996). Teachers’ professional lives: Aspirations and actualities. In I. F. Goodson & A. Hargreaves (Eds.), Teachers’ professional lives (pp. 1-27). Washington, DC: Falmer Press.

Helsby, G., & McCulloch, G. (1996). Teacher professionalism and curriculum control. In I. F. Goodson & A. Hargreaves (Eds.), Teachers’ professional lives (pp. 56-74). Washington, DC: Falmer Press.

Herr, K. (1999). Unearthing the unspeakable: When teacher research and political agendas collide. Language Arts, 77, 10-15.

Hibbert, K., & Iannacci, L. (2005). From dissemination to discernment: The commodification of literacy. The Reading Teacher, 58(8), 716-727.

Hughes, E. C. (1958). Men and their work. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Irvine, P. D., & Larson, J. (2001). Literacy packages in practice: Constructing academic disadvantage. In J. Larson (Ed.), Literacy as snake oil: Beyond the quick fix (pp. 45-70). New York, NY: Lang.

Jaafar, S. B., & Anderson, S. (2007). Policy trends and tensions in accountability for educational management and services in Canada. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 53(2), 207-227.

Larson, M. S. (1977). The rise of professionalism. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Lingard, B. (2010). Policy borrowing, policy learning: Testing times in Australian schooling. Critical Studies in Education, 51(2), 129-147.

Lingard, B. (2011). Policy as numbers: Ac/counting for educational research. The Australian Educational Researcher, 38(4), 355-382.

Los Angeles Unified School District. (n.d.). Fidelity of implementation. Retrieved from http://www.lausd.k12.ca.us/lausd/offices/hep/news/fidelity.html

MacGillivray, L., Ardell, A. L., Curwen, M. S., & Palma, J. (2004). Colonized teachers: Examining the implementation of a scripted reading program. Teaching Education, 15(2), 131-144.

MacNeill, P. (2014). Ghiz’s education policy: Last is OK. Retrieved July 27, 2014 from http://www.peicanada.com/second_opinion_paul_macneill_publisher/columns_opinions/ghiz%E2%80%99s_education_policy_last_ok

Manitoba Government. (n.d.). Education and Literacy. Retrieved July 27, 2014 from http://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/

McMillan, J. H., & Wergin, J. F. (2010). Understanding and evaluating educational research (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Merriam, S. B. (2014). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Monroe, M. C., & Adams, D. C. (2012). Increasing response rates to web-based surveys. Journal of Extension, 50(6), 6-7.

New Brunswick Department of Education. (2008). Reading and writing achievement standards.

New Brunswick Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. (2013). Framework for provincial assessments. Retrieved July 27, 2014 from http://www.gnb.ca/0000/results/pdf/AssessmentFrameworkDocument.pdf

Nulty, D. D. (2008). The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(3), 301-314.

Office for Standards in Education. (2002). The national literacy strategy: The first four years 1998-2002. Retrieved May 22, 2011, from http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/Ofsted-home/Publications-and-research/Browse-all-by/Education/Curriculum/English/Primary/National-Literacy-Strategy-the-first-four-years-1998-2002

Ogier, J. (2005, November). The response rates for online surveys — a hit and miss affair. Paper presented at the 2005 Australasian Evaluations Forum: University Learning and Teaching: Evaluating and Enhancing the Experience, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Pease-Alvarez, L., & Samway, K. D. (2008). Negotiating a top-down reading program mandate: The experience of one school. Language Arts, 86(1), 32-41.

Pratte, R., & Rury, J. L. (1988). Professionalism, autonomy, and teachers. Educational Policy, 2(1), 71-89.

Prince Edward Island Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (PEI-DEECD). (2012). Guidelines for running / reading record assessment for kindergarten to grade 6. Summerside, PE: Prince Edward Island Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

Kurial, R. (2005). Excellence in education: A challenge for Prince Edward Island. Retrieved from http://www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/task_force_edu.pdf

Scholastic. (2007). Moving up with literacy place. Markham, ON: Scholastic Canada.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schwab, J. J. (1983). The practical 4: Something for curriculum professors to do. Curriculum Inquiry, 13(3), 239-265.

Sciulli, D. (2005). Continental sociology of professions today: Conceptual contributions. Current Sociology, 53(6), 915-942.

Shannon, P. (1989). The struggle for control of literacy lessons. Language Arts, 66(6), 625-634.

Shannon, P. (1990). The struggle to continue: Progressive reading instruction in the United States. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Shannon, P. (2000). “What’s my name?”: A politics of literacy in the latter half of the 20th century in America. Reading Research Quarterly, 35(1), 90-107.

Shelton, N. R. (2005). First do no harm: Teachers’ reactions to mandated reading mastery. In B. Altweger (Ed.), Reading for profit: How the bottom line leaves kids behind (pp. 184-198). Ann Arbor, MI: Pearson Education.

Spiegel, D. L. (1998). Silver bullets, babies, and bath water: Literature response groups in a balanced literacy program. The Reading Teacher, 52, 114-124.

Talbert, J. E., & McLaughlin, M. W. (1996). Teacher professionalism in local school contexts. In I. F. Goodson & A. Hargreaves (Eds.), Teachers’ professional lives (pp. 127-153). Washington, DC: Falmer Press.

United States Department of Education. (2002.). No child left behind. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02/107-110.pdf

Western School Board of Prince Edward Island (WES-PEI). (2011). Western School Board of Prince Edward Island strategic direction 2011-2013. Retrieved July 2, 2013, from http://www.edu.pe.ca/wsb/schoolboard/materials/strategicplacemat.pdf

Wyse, D., & Opfer, D. (2010). Globalization and the international context for literacy policy reform in England. In D. Wyse, R. Andrews, & J. Hoffman (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook series (pp. 438-447). New York, NY: Routledge.

Wyse, D., & Torrance, H. (2009). The development and consequences of national curriculum assessment for primary education in England. Educational Research, 51(2), 213-228.