Mobilizing Knowledge via Documentary Filmmaking — is the Academy Ready?

Two researchers, two purposes, two different research topics — one common question — might documentary filmmaking serve as an alternative form of “publication” within the academy? This article explores how documentary filmmaking might serve as an alternative form of legitimate scholarly work within the deeply embedded “publish-or-perish” culture of universities. We examine this possibility by narrating how two colleagues arrived at this notion independently, and how a call for papers for this journal served as a catalyst for sharing how we merged our interests, and why we feel documentary filmmaking might serve as a powerful medium for research knowledge mobilization.

This paper first provides a selected overview of documentary filmmaking as it relates to other related film genres such as ethnographic and anthropologic film, and follows with an examination of the notion of visual research in the literature. Next, we describe how we integrated documentary filmmaking within our scholarly interests. Our joint findings suggest that documentary filmmaking might be a legitimate and alternative form of scholarly work.

A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Academic research is typically written in a style and for venues that remain largely inaccessible by the general public and even by the practitioners who might benefit from it. Glesne (2010) suggested that to make our work accessible “to others beyond the academic community…means creating in forms that others will want to read, watch, or listen to, feel and learn from the representations” (p. 262), such as “drama, poetry, and narrative” (p. 245). Eisner (1997) added that alternative forms of data representation “make empathy possible when work on those forms are treated as works of art,”, “provide a sense of particularity that abstractions cannot render,” generate “insight,” and invite “attention to complexity” (p. 8).

Weber (2008) also suggested that visual images serve as effective tools for researchers in a variety of contexts within the research process. Examples of how visual images could be incorporated into various phases of research include: the production of visual images by researchers or participants, the use of visual images (that already exist) as data or “springboards for theorizing” (Weber, 2008, p. 48), the use of visual images to produce other data, the use of visual images for feedback and documenting research processes, and the use of visual images to interpret or represent their work (Weber, 2008). We address several of these examples put forth by Weber, however, the key focus of this work is based on the latter example — the use of visual images to interpret or represent work via visual research which in this case takes the form of documentary filmmaking.

Theoretical, epistemological, and technical debates regarding documentary and ethnographic film is abundant in the literature (Nichols, 2010; Ruby, 2008), and lie beyond the scope of this paper; however, a brief distinction between these genres of film warrants attention since part of the distinction serves as an underlying reason why we deliberately chose documentary filmmaking as an alternative form of scholarly publication. Documentary filmmaking, a term coined by Grierson in the 1930s as a “creative treatment of actuality” (as cited in Nichols, 2010, p. 6), continues to be a genre and term debated by documentary film theorists (Bergman, 2009). Neutral representation, the filmmaker’s influence, the type and format of documentary, and the audience are examples of several areas of tension within the documentary film genre (Bergman, 2009).

We base our conceptual understanding of documentary film on the propositions put forth by Nichols (2010). Grounded loosely in Grierson’s original definition of “creative treatment of actuality,” Nichols suggested that documentary films are comprised of three key elements. First, they honour and are grounded in “real” events and circumstances that happened, as opposed to being grounded in “unverifiable” (p. 7) situations. Documentary films are also about “real” individuals who are not performing roles, although one might argue the nature of “performance” especially when being filmed (Nichols, 2010). Lastly, drawing from Grierson’s “creative treatment” notion, Nichols proposes that documentary films tell a story and that “the story is a plausible representation of what happened rather than an imaginative interpretation of what might have happened” (p. 7). Like documentary film, the ethnographic film genre is also one of ongoing debate (Heider, 2006; Nichols, 2010; Ruby, 2008). For example, if framed within Ruby’s (2008) assertion that ethnographic film should refer to the work of anthropologists, ethnographic film can be described as a type of film grounded in anthropological work. Some scholars such as Heider (2006), however, approach the ethnographic film definition in a less restrictive manner, acknowledging that ethnographic films could range in their degree of “ethnographicness” (p. 2). We acknowledge the “ethnographic” in both Ruby’s and Heider’s descriptions, yet we did not want to limit the methodological possibilities in using filmmaking as an alternative form of scholarship. So, we frame our work within an arts-informed research framework as a “methodological enhancement” (Cole & Knowles, 2008, p. 60), to our other research approaches, and within the documentary film context set forth by Nichols (2010), as well as a visual research perspective (Pauwels, 2011; Pink, 2012; Weber, 2008).

CONTEXT

We are not professional filmmakers, nor do we claim to be scholars of film studies. We are colleagues and faculty members within a faculty of education at a mid-size and technology-focused university in southern Ontario, at different points in our academic careers. While there are similarities in our work, our research interests and methodologies are different. Diana, a self-proclaimed “recovering positivist,” previously approached most of her research from a quantitative and mixed methods paradigm, while Janette engages in predominantly qualitative research. As researchers at a technology-focused university, we are interested in not only how multimedia influences teaching and learning, but we also each independently discovered how documentary filmmaking might serve as an alternative form of research in process and product. This special issue’s call for papers served as a catalyst to begin informal discussions between two colleagues regarding the abundance of multimedia within research yet the scarcity of such multimedia within with scholarly publications. After discussion and examination of each other’s work, we realized that our work, although divergent in nature, led us to similar conclusions regarding the potential power of documentary filmmaking as a form of knowledge mobilization. While on a faculty writing retreat, the authors viewed each other’s work in this area for the first time, and found a number of commonalities, yet some important differences in our approaches to using video in our research. This conversation prompted us to explore in more depth some of our epistemological notions and how they overlap.

DEFINING ELEMENTS OF DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKING

This section describes our individual experiences with documentary filmmaking as it relates to our scholarly work, and following Cole and Knowles (2008), we pay particular attention to the defining elements of this medium to examine our research purposes and methods.

Commitment to documentary filmmaking

Diana: Inspired by a comment made by my 74-year-old mother while helping me unpack boxes in my new academic office at a southern Ontario university, I unintentionally stumbled into 1) making my first short documentary film, and 2) a new research methodology. “Look over there,” she motioned wistfully. “I can see the house where we first lived when we moved to Canada.” She shook her head, marveling at the discovery. “We were poor immigrants… and now my daughter is a professor at a university.” Her eyes welled up with tears, as did mine. I instinctively reached for my camera, something I did frequently upon the recent completion of a 40-hour intensive and introductory documentary film course that focused on the technical aspects of documentary filmmaking such as camera components, lighting, and interview techniques. My previous research integrated digital video as part of the data collection during interviews, and served as the impetus for me to learn more about the technical aspects of documentary filmmaking to continue incorporating digital video into future research. Upon completion of my course, I frequently practiced capturing moments on camera to improve my skills. “Oh you and that camera,” she turned away, wiping her eyes, “my English.” I turned off the camera. I asked if she would like her granddaughters to know — to really understand — where she came from, her history, her struggles, and her victories. At the time, my request to capture my mother’s story was for personal reasons — to help her tell her story for her grandchildren, and perhaps their grandchildren. She nodded slowly and turned back towards the window. “Yes, they need to know…. If only I knew then what I know now, I would not have worried so much.” With that phrase, my first short documentary, Coffee. Cup. (Petrarca, 2013) began, as did my unexpected transition into the rich qualitative world of interpretive biography, a method that studies the life experiences of a person by examining narratives, accounts, and personal documents that describe “turning-point moments” or moments that leave marks on the life of an individual (Denzin, 1989, p. 7).

Janette: As a former secondary English and drama teacher, I value the power of the story and particularly, the importance of lifting that story off the printed page and breathing life into it. My early research working with adolescents creating digital poetry (Hughes, 2007, 2008a; Hughes & John, 2009) inspired me to turn again to the notion of performing research through an arts-based lens. Unlike Diana, I knew from the outset that I would be creating a research documentary, and I specifically applied for a SSHRC dissemination grant for this very purpose. In 2011, I received an Early Researcher Award from the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation (MRI) for a research project entitled, “Fostering Globally and Culturally Sensitive Adolescents: Social Action Through Digital Literacy.” The research examined the relationship between digital media and adolescents’ understanding of global issues while immersed in using digital media and also explored how the public performances of students’ digital texts might reshape the relationship between educational stakeholders (students, teachers, parents, schools) and the wider community both locally (within the classroom, school and neighbourhood) and globally (through the Internet, specifically via social media). As part of the three-year research plan, students shared their work in a variety of venues, both within and beyond the classroom context, including on a class blog, on the project website, at community art galleries, and on community organizations’ websites, such as War Child Canada.

I wanted to disseminate key findings from this research through both traditional and more innovative methods, and I received the SSHRC dissemination grant to accompany the MRI grant. In addition to sharing our findings with the scholarly and educational communities through conference presentations and articles in refereed journals, I decided to create “research performances” similar to the ones created by the student participants. We (the research team) purposefully created a parallel between the classroom focus on performance and the methods of research dissemination, by relying on performance ethnography methods. The ethnographic performances were shared with the students and teachers, thus returning the stories to the classrooms and people from where they emerged. These performances are also posted on the project website, shared at workshops and conferences, and shared publicly through YouTube, social networking sites, and not-for-profit organizations with the target audience being K-12 students, teachers, parents, educational organizations, not-for-profit organizations, and the public.

Methodological integrity

Cole and Knowles (2008) argued that the rationale for using a particular medium to guide the research must be “readily apparent by how and how well it works to illuminate and achieve the research purposes” (p. 12). In retrospect, Diana realized that the inspiration that served as the catalyst for her personal documentary filmmaking project reflected a deeper exploration of a biographical problem or question. What began as an endeavor to simply capture a family story, blossomed into a deep desire to understand more deeply her mother’s struggles and joys in learning a new language as an immigrant in the 1960s. For Janette, the decision to create a documentary depicting the research story was based in part on an acknowledgement of the important role of community, and a commitment to the public sharing of knowledge and understanding, as a key component of the research she was doing with the students.

Diana: Growing up, my mother spoke frequently of her struggles of isolation, embarrassment, and learning English as a newcomer to Canada. Witnessing my mother’s emotion evoked by the irony of seeing my childhood home from my university office, where many years ago she experienced her turning-point moment, ironically served as a profound turning-point moment for me as an educational researcher. Even though I heard my mother’s anecdotes many times before, did I truly listen to what she revealed? Did I fully understand? I realized that moment that I did not fully understand but that I needed to document my process of understanding. I turned to my video camera to capture her experiences. Denzin (1989) describes such epiphanies as “interactional moments and experiences which leave marks on people’s lives” (p. 70). Although my initial intention in creating the documentary film was personal in nature, it was through the process of recording and making editorial decisions that I discovered that documentary filmmaking, if guided by a question and methodological framework, could reflect an alternative form of scholarly publication.

Janette: We found that the performative potential of digital media facilitated exploration and creation of digital texts lending voice to the local and global issues that adolescents were most concerned about, for instance, cyberbullying, the impact of war on children, and how media contributes to one’s perception of body image. The texts they created were, in turn, shared with others as a way of engendering social change.

The creative inquiry process

Both researchers have different methodological approaches to their research; however, both apply systematic guidelines in the collection and analysis of data in ways that tend to be somewhat linear. Notably, this was not the case for Diana in the research she came to do with her mother. The project was not intended to be research oriented, but rather a personal tribute to her mother and an attempt to capture her story for future generations. As she progressed through the project, however, she began to draw parallels between the documentary filmmaking process and qualitative research methods, nudging Diana to consider the similarities between her previous data collection methods and her amateur documentary filmmaking processes.

Diana: Prior to this first documentary, I used video as a teaching tool to capture students’ creative endeavours, to create procedural or instructional types of video, or to simply record interviews (for audio transcription purposes) to supplement quantitative data in mixed methods research. With the purchase of my new camera, I began documenting my nieces’ learning-to-read experiences, the stillness of nature, and my mother’s tomato sauce ritual. While I had footage of family members and events, I had yet to practice the art of video interviewing. I wanted to practice setting up and conducting on-camera interviews as learned in my documentary course, and I welcomed the opportunity to practice with my mother. I practiced setting up the camera, the background, the lighting, and asking her open-ended questions during our conversation, to which she often responded using stories. I captured those stories on video. Figure 1 demonstrates an example of an on-camera interview incorporated into the documentary.

FIGURE 1. Screenshot of example of interview video clip

As I began the video recording (i.e., data collection), I quickly realized that the processes I incorporated to record my mother’s daily behaviours and our conversations greatly resembled data collection strategies I incorporated into previous research studies. I did not have a formal protocol to guide my field procedures and interviews, but in retrospect, I realized I followed a similar routine once a week for 6 weeks attempting to maintain consistency. During my weekly visits with my mother, I set up my tripod and camera to record some of our conversations in between her routine behaviours such as making appointments, running errands, making coffee, or cooking a meal. I refrained from staging situations and simply wanted to capture moments of her everyday life. I routinely asked questions much like I did in previous research where I incorporated semi-structured interviews. Although the questions were not formally developed prior to our weekly meetings, I did often reflect before and after our visits, contemplating areas I would like to learn more about. I wanted to gain a deeper understanding of her experiences and behaviours much like I would have when interviewing participants in previous research projects. I also faced many immediate decisions that ultimately were guided by the purpose of my project, which in this case was to learn more about my mother’s “learning-to-speak English” story and the complexities surrounding her struggles.

Janette: In contrast to Diana’s work, the intent to create a research documentary based on classroom interactions, student work, and interviews as data was an explicit goal from the beginning. When I began teaching in the preservice teacher education program, I created an e-book (Teaching Language and Literacy, K-6) for our teacher candidates. The e-book includes video of teacher / student interaction as well as a variety of classroom activities. The teacher candidates comment that the videos bring the concepts (i.e., guided reading or literature circles) alive in a way that is not possible through static images or print text alone. At the same time, I was involved in a SSHRC research project with a focus on “Students as Performance Mathematicians” and I contributed my expertise in the area of drama and digital literacies to help students express their understanding of mathematical concepts through multiple modes of expression. These experiences, combined with a growing movement in Canada by granting agencies to promote alternate forms of dissemination, led to my decision to use performance ethnography methods (Denzin, 2003; Madison, 2006) and capture still images, video footage and sound bites of classroom interactions. We had one video camera set up in the classroom that was left to record from a wide-angle position and another video camera that was hand-held to capture moments in the teaching and learning process from a closer perspective. In addition, we took hundreds of still images of students working on project tasks (predominantly using digital technologies) and also captured images of student products (see Figures 2 & 3).

FIGURE 2. Creating a Tagxedo

FIGURE 3. Student Tagxedo

Just like a traditional article, our documentary included images of student work and comments by students and teachers. The difference in a documentary is that we see these on a video, which tends to be more intrusive and shares much more evidence than a static picture — ethically, decisions about which videoclips to include requires much more scrutiny. As part of our research protocol we obtained district school board, parental and participant consent to use the still images and video footage; however, even though students and parents gave permission in advance, we asked students again before video taping whether it was okay to record them or take a photo of their work. If they hesitated or we sensed that they were not comfortable, we did not proceed. As noted earlier, we also had a camera set up to record classroom activities at all times so they were sometimes unaware that they were being recorded. Because we felt this was obtrusive, we showed the documentary to them before it was made public in order to confirm that the way they were represented was acceptable. We found that students and teachers were equally eager to appear in the documentary. Sharing educational research through performance-based video clips with educators, parents and the public in general helps make research findings tangible and accessible.

The subjective and reflexive presence of the researcher

Although Janette was not as close to her research participants as Diana was to her’s, both researchers shared a subjective and reflexive presence in our research. In both of our experiences, data analysis and video editing went hand-in-hand and decisions about what material or footage to include and exclude was informed by our respective aesthetic sensibilities as well as our desire to tell an authentic story or represent classroom events accurately.

Diana: Because this project began as a personal exploration of my mother’s learning-to-speak English experiences, I did not have a formal analytical framework or formal underlying theoretical constructs guiding the editing / analysis. In retrospect, however, the analytical techniques used in my previous qualitative analyses permeated my editing processes. For example, I used the topics that emerged from the interviews as a guide for “coding” the reams of observational video footage. The iterative viewing of these video clips during the laborious editing process helped me notice descriptive patterns, similar to my previous pattern-coding (Miles & Huberman, 1994) processes when analyzing qualitative data.

As topics of convergence and divergence (Patton, 2002) emerged, I attempted to locate segments of video to best reflect those topics for the final documentary. While editing this personal project, the “researcher” in me wondered about other immigrants’ experiences in Canada, and I began to search for research studies on the topic. The “newcomer to Canada” literature, consistent with the topics that surfaced in the analysis or editing phase of this work further guided my selection of video clips, archival photographs, and text / quotes to insert within the documentary film.

Janette: Video editing is an extremely time-intensive endeavour and as Diana notes, the repeated viewing of the same clips gives the researcher-editor an intimate connection with the data. The analysis was qualitative, in keeping with the established practice of in-depth studies of classroom-based learning and case studies in general (Stake, 2000). As noted earlier, data consisted of (a) detailed field notes, (b) students’ writing, (c) transcribed interviews with students and teachers, (d) the digital texts created by students, and (e) video recordings of selected learning / authoring activities. For the purposes of the documentary, we focused on the interviews, the digital products generated by the students and the still and video recordings of the classroom activities. Because of the complex blending of multimodal data elements, we used the digital visual literacy analysis method of Hull and Katz (2006) of developing a “pictorial and textual representation of those elements” (p. 41), that is, columns of the spoken words from recordings juxtaposed with original written text, the images from digital texts, and data from interviews, field notes and video recordings. This facilitated the “qualitative analysis of patterns” (p. 41). The analytic methods included thematic coding and critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, 1995). The data was read and coded for major themes and sub-themes across data sources, and the codes were revised and expanded as more themes were identified. In the selection of data for the creation of the documentary, we were particularly interested in moments that might be interpreted as “turning points” (Bruner, 1994) in the representation of identity and / or the conceptual understanding of social justice issues for the students, and “aha” moments for the teachers as they observed their students engage in the learning process. This required poring over the video data to find just the “right” clips that would tell the story of the research in those classrooms.

Centrality of audience engagement

In assembling the final documentary, many difficult decisions had to be made about which information to include and, possibly even more difficult, which information to leave out. The selection process was very much based on our desire to both inform and engage an audience in a topic we each identified as meaningful. For Diana, that audience initially was her mother’s grandchildren but expanded to include extended family and then the scholarly community, and for Janette, the target audience was parents, students, teachers and ultimately, policy-makers.

Diana: Upon completion of data analysis / video editing processes, the themes that emerged from the interviews and observations related to issues of social isolation, frustration, and fear of Margherita’s “learning-to-speak-English” experiences as an Italian-Canadian immigrant. These themes represented what Denzin (1989) would describe as “moments of crisis” (p. 70), to the point where Margherita contemplated leaving Canada to return to her homeland. Margherita insisted that her life in Canada changed, taking a turn for the better, after learning her first two English words at a local high school offering a free English as a Second Language course in the mid-1960s. The two words, “coffee” and “cup,” featured prominently in the final documentary, and along with the themes that emerged from the analysis, guided the selection of video clips to tell Margherita’s story. In discussion with Janette, I realized that by making editing decisions to tell my mother’s story, I was actually excluding other stories from being told. For example, there were additional anecdotes shared by my mother about her decision-making processes, alongside my father, to come to Canada; however, these anecdotes were not included in the final documentary. I wonder how the story might be different if these anecdotes were actually included in the film. Moving forward, greater reflection regarding the “untold” stories will be an additional factor in my editing decisions.

When locating and selecting clips to reflect the themes and topics that emerged in the interviews and observations, additional editing decisions were made to echo the emotion and tone captured visually in the video clips of the observations and interviews. Inclusion of music, images, words, photos, narration, quotes from newcomer to Canada research, and supplementary B-roll footage were also carefully selected to “truthfully” tell Margherita’s story. Figures 4 and 5 are examples of how archival photos and literature respectively were included in the documentary film.

FIGURE 4. Old photo of village included in documentary

FIGURE 5. Example of literature incorporated into documentary

Rather than write a text-based biographical narrative, the final product to reflect the “findings” was a short documentary, Coffee. Cup. (Petrarca, 2013) largely due to my mother’s initial melancholic comments made in my office that served as the impetus to begin this endeavour. Because the intended audience was my mother’s grandchildren, and possibly future generations, I wanted to capture the gestural and facial expressions via video so that perhaps other viewers would “see” her story in a more emotive manner than text.

Janette: There was a temptation to include more of the students’ images and work to honour their participation in the project. We had to continually remind ourselves of our purpose and the limitations we faced, for example, keeping the documentary under 22 minutes (the standard length for a one-hour television segment). We decided to frame the documentary with comments by the researcher, explaining the research and the activities the students engaged in throughout the study. This framework enabled us to better structure the documentary and kept us focused on our purpose, which was to make the research findings more accessible to the general public. The juxtaposition of the scholar speaking about the purpose of the research with various still shots and videoclips of the research project offers the audience a rich and more personal look into the research itself. Still images of the students engaged in learning activities (see Figure 6) are interwoven with the classroom teachers commenting on the project (see Figure 7).

FIGURE 6. Working on MacBooks

FIGURE 7. Still photo from interview clip with classroom teacher

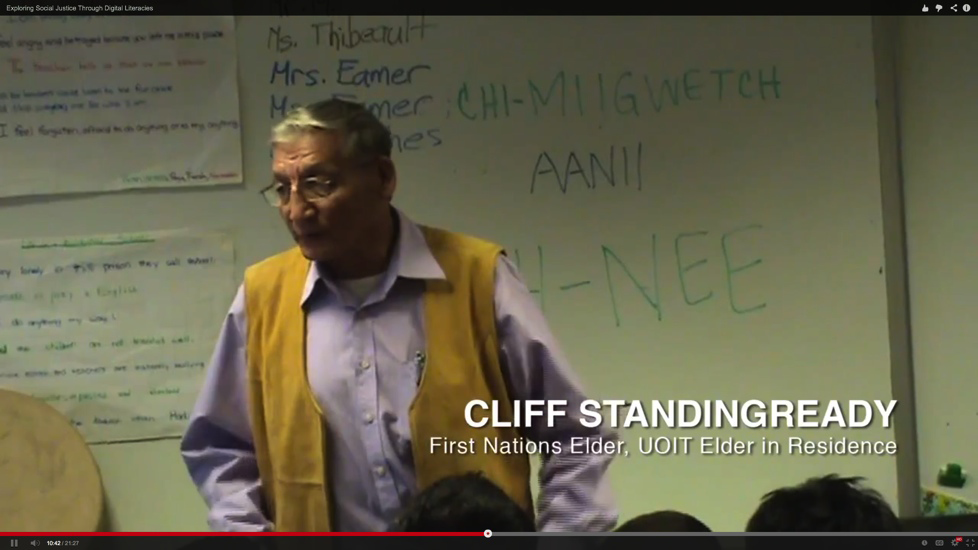

As Diana notes, it is difficult to decide what to include and what to omit as each decision serves to tell the story in a different way. We made decisions based primarily on the quality of the photos, but also tried to ensure that we included both boys and girls, and gave voice to the teachers and guests in equal measure. Video clips of a Lakota elder (see Figure 8) and award winning aboriginal musician Tracy Bone (see Figure 9) shown engaging with the students enable the viewer to experience, in part, what the students experienced in person. Snippets of student generated digital texts offer the audience a glimpse of the learning that took place from the student’s perspective. The research documentary, Exploring Social Justice Through Digital Literacies (Hughes, 2013) can be viewed on YouTube at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dZOt6RDhkVY.1

FIGURE 8. Still photo from video footage of First Nations Elder

FIGURE 9. Still photo from video footage of Tracy Bone singing

THE QUALITIES OF “GOODNESS” AND OUR DOCUMENTARIES

We have provided the context of our independent documentary filmmaking experiences, and described how independent of one another, the process by which we incorporated documentary filmmaking into our respective projects through a discussion of the elements of this medium. We now engage in a critical examination of how well our documentary films serve as an alternative form of scholarly work within educational research using the work of Cole and Knowles (2008) as a guide. Cole and Knowles (2008) suggested that a research study that encompasses intentionality, researcher presence, aesthetic quality, methodological commitment, holistic quality, communicability, knowledge advancement, and contributions, might potentially add to the arts-informed research agenda — “that of enhancing understanding of the human condition through alternative (to conventional) processes and representational forms of inquiry, and reaching multiple audiences by making scholarship more accessible” (p. 65). Guided by our claim that the academy ought to consider documentary film as an alternative form of scholarly work and knowledge mobilization outside the walls of the university, we consider these elements to support the claim for documentary film as an alternative form of inquiry accessible to a wider audience outside of the walls of the academy.

Intentionality and contributions

Our intentions for creating these documentaries were driven by our respective moral commitments to transformation (Cole & Knowles, 2008). Janette’s intention to explore the impact on adolescents’ learning when given opportunities to create digital texts for a wider audience and engage with social justice issues on a global scale was driven by both moral and intellectual purpose. The research positions adolescents as agents of change as they produce digital texts based on issues identified through the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, such as the impact of war, child labour, poverty and environmental concerns. Diana’s intention was also deeply rooted in a moral commitment to share her mother’s poignant story with her family so that future generations would be able to see, hear, and appreciate the struggles she faced as a newcomer to Canada to make a better life for those who would view the final film. Midway through the process, however, by seeking additional literature and data about newcomers to Canada, unknowingly, Diana’s original moral purpose to capture and share her mother’s personal story with family members broadened to include an intellectual purpose. Personally moved by her mother’s appreciation for any opportunity to learn, Diana’s intention expanded. She wanted to share with wider audiences how the power of education transformed the life of an immigrant woman contemplating to leave her new country due to feelings of isolation and frustration with wider audiences. Related to the moral purpose of arts-informed research include the contributions of the work within theoretical and practical contexts, and their theoretical and transformative potentials (Cole & Knowles, 2008). We both sought the documentary film art form so that audiences within and outside of the academy walls could have the opportunity to view the work from a theoretical and / or transformative position. We see ourselves not only as researchers contributing to the scholarly advancement of knowledge but we also strive to serve as agents of change.

Methodological commitment

With the proliferation of digital video recording technologies available to consumers, and with an increase of researchers in behavioural and social sciences and the humanities exploring visual research (Pauwels, 2011), it seems logical that forms of “publication” other than the peer reviewed text-based scholarly journals or books should also be considered scholarly by the academy, if framed within a research context.

Our conduct throughout the documentary filmmaking process provides evidence of principled processes throughout various stages of the documentary filmmaking. For example, Janette, whose intention was research oriented at the onset of the work, paid careful attention to ethical considerations, as required by researchers conducting work with human participants. Diana, on the other hand, whose documentary film was originally not research oriented in nature, reflected frequently throughout the filmmaking process on her previous research work with other human participants, being careful to not appear coercive and instinctively seeking approval to film or continue filming, particularly emotional interviews. These actions were guided by her previous work with research participants. We reflected frequently on our documentary filmmaking decisions to maintain the integrity of the research / film and the participants.

Researcher presence and holistic quality

The presence of the researcher in an arts-informed research is another quality of goodness as described by Cole and Knowles (2008). Janette’s presence as narrator within the documentary is explicit — she appears in the video and her voice provides the narration (Cole & Knowles, 2008). Diana, who was extremely close to the subject of her documentary, was also “present” by implication. Like Janette, Diana also narrated the documentary when its intention was for personal (i.e., family) use. Upon broadening her intention for research purposes, she re-recorded the narration, substituting her voice for the voice of a friend experienced in voiceover work. Ironically, her rationale for removing herself from the narration was to give the final product a more neutral position as a work of research. Interestingly, audience members who viewed both versions of the documentary preferred her voice as narration, indicating it felt more “real.” Her motivations for re-recording the narration clearly reflects remnants of her positivistic paradigm, and only in discussion with Janette did Diana realize that the “realness” expressed by viewers reflected the “signature or fingerprint of research-as-artist” (Cole & Knowles, 2008, p. 66), and that by removing her presence an element that gave the work realness was removed. How would other members of the scholarly community with paradigmatic differences view the research?

The re-recording was in part largely due to the holistic quality of the documentary film, described by Cole and Knowles (2008) as somewhat contradictory to the more traditional and linear types of research experienced by Diana, where there existed more distance between the researcher and participants. Through conversations with Janette, the more integrated nature and ontological underpinnings of arts-informed research became clearer, and resulted in a more holistic approach to research by both of us. Again, how do we deal with the traditionalists? How do we convince them that this is research?

Aesthetic quality

As previously mentioned, we do not claim to be filmmakers but rather researchers advancing knowledge through a visual form — documentary film. In both cases, the film was the “medium through which research purposes are achieved” (Cole & Knowles, 2008, p. 66), even though the purposes of our research projects varied. As part of our respective data collection phases, we have both described elements related to digital video recording such as setting up shots, angles, lighting, and interview techniques. When selecting shots in post-production, we also reflected on how the final product (i.e., a visual form, the documentary film) influenced the process of data collection and final output. For example, how do the aesthetic qualities of captured video footage influence editorial choices for the final documentary? How do aesthetic qualities influence data collection? Aesthetic decisions regarding music, narration, and images during editing were also considered from both aesthetic and research perspectives. We spent considerable time discussing our decisions and the underlying motivations for capturing data and making decisions in the post-production phase of the process. For example, Diana’s mother referenced several times in raw footage that was not included in the final documentary, how her decision to come to Canada was made real when she was sitting on the deck of the ship in Naples with her husband, waving tearfully to their emotional family members at the port. As a result, Diana searched tirelessly for a sound byte of a ship’s horn to accompany the archival photo of the actual ship that transported her parents to Canada to honour that moment via sound. Similarly, Janette wanted to include music to fill in the gaps between narration and teacher interview clips, and found it challenging to identify copyright-free music that would complement the documentary. Much like data collection and analysis for the purpose of a more traditional research paper, we believe constant reflexivity regarding aesthetic decisions, framed within the original question(s) guiding the visual research is critical to maintain the rigor the academy demands from its researchers.

Communicability

Our underlying intentions of creating a documentary film to share our respective “stories” included the communicative potential of the form (Cole & Knowles, 2008). Our underlying assumptions that documentary films attempt to share “real” happenings within the world (Aufderheide, 2007; Nichols, 2010) in a manner that is creative or imaginative (Nichols, 2010) guided our decisions to intentionally select documentary filmmaking as a medium to advance knowledge and make scholarship more accessible (Cole & Knowles, 2008).

We each selected methods to explore our respective topics in a manner that would “provide the best understanding of a research problem” (Creswell, 2003, p. 12), but also to mobilize the “real” occurrences to others outside of the academy. We each turned to visual images to guide our work (Weber, 2008), culminating in a documentary film as a way to represent the output or presentational format (Pauwels, 2011) of our “truth” seeking. Weber (2008) maintained that such integration of visual images to guide work could benefit the social sciences and humanities in a variety of ways:

To sum up, this ability of images to evoke visceral and emotional responses in ways that are memorable, coupled with their capacity to help us empathize or see another’s point of view and to provoke new ways of looking at things critically, makes them powerful tools for researchers to use in different ways during various phases of research. (p. 47)

Knowledge advancement

As noted by Cole and Knowles (2008), “the knowledge advanced in arts-informed research is generative rather than propositional and based on assumptions that reflect the multidimensional, complex, dynamic, intersubjective, and contextual nature of human experience” (p. 67). We are aware that we consciously chose to tell our stories in specific ways, in order to best communicate our desired themes and purposes. Our real world purposes and problems in our documentary films varied in nature, as did our approaches, but both films had underlying questions that sought to explore various “truths” and illuminate the lived experiences of the research participants via “visual” methods as a way to explore and share particular phenomena. We both selected the visual medium of digital video because we believed that “insight in society can be acquired by observing, analyzing, and theorizing its visual manifestations: behavior of people and material products of culture” (Pauwels, 2011, p. 3). Framed within a research perspective, we sought to examine what Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004) describe as lowercase “t” truths or temporary truths or knowledge that as researchers we obtain through our research, and could change over time. As Creswell points out, “truth is what works at the time; it is not based in a strict dualism between the mind and a reality completely independent of the mind” (2003, p. 12). Both final documentary films reflected stories of “plausible representation of what happened” within the individual projects as opposed to an “imaginative interpretation of what might have happened” (Nichols, 2010, p. 7).

CONCLUSIONS

We believe that a documentary film can capture that “provisional truth” if the researcher / documentary filmmaker presents findings in a manner that keeps ethical considerations at the forefront of the editing process when preparing the final output or film (Hampe, 2007). We agree with Hampe (2007), who points out,

the ethics of documentary filmmaking should concern reflection on the practice of documentary filmmaking. It is not about judging individual actions or describing what is the right thing to do in a given situation. Instead, it is about the principles that inform deliberations and decisions about the right thing to do as a documentary filmmaker. (p. 531)

The research documentary, as it was employed by both authors, is both an aesthetic performance and an attempt to tell that provisional truth of which Hampe (2007) speaks. The documentary film’s potential to mobilize knowledge in similar ways to a traditional research paper, especially if the documentary filmmaking process follows the trajectory of research processes, might serve as a loose guide to legitimize the final product as scholarly work. Indeed, a research documentary allows us to hear the voices of the participants directly in a way that allows us to capture the nuances of gesture, facial expression and vocal intonation and emphasis. If similar processes are used and attention is paid to questions of validity, we might ask whether documentary filmmaking could serve as an alternative form of “publication” within the academy.

Given the increasing access we have to digital media, mobile devices and ubiquitous use of the Internet, we should be redefining or reconsidering our current approaches to data collection, analysis and dissemination. Shrum, Duque, and Brown (2005) suggested we consider digital video as an “innovation in research practice rather than simply a new medium for recording social behaviour” (p. 17) in our 21st century world. Innovation is not simply a product or process that does something different, nor can it be reduced to something that simply improves a particular condition, but rather innovation refers to both change and improvement (Vaughan, 2013).

Our respective documentary works and discussion helped us realize that digital video is not “simply a new media” to gather data or “record social behaviours,” but rather we suggest the documentary filmmaking process and product as research did something “different” and “better.” We believe this work is innovative because it refers to both change in how we approached and considered data collection, analysis, and mobilization, and improvement of data interpretation and mobilization.

First, by incorporating a multisensory video-based final product — intended to be viewed rather than read by an audience — into the research, as researchers, we not only considered the collection and analysis of data, but also the preparation of the data for dissemination purposes. This required us to be mindful of the final film, which introduced a “performative” element into the research process. Hughes (2008b) suggested a metaphor of “research as performance” (p. 30) might be a useful way to consider research using new media, which includes digital video for documentary filmmaking purposes. For example, rather than simply setting up a camera to capture interviewees or observe participants for data collection purposes, our respective considerations of the data shifted to include the more aesthetic components of video recording such as lighting, background objects, or sound quality. These video clips now held a dual purpose. They represented pieces of data to be analyzed, and potential nuggets of video to be incorporated into the final film. For us, this changed how we approached data collection and / or analysis as we reflected more frequently on the validity of the data. We continually considered whether the video clips represented the collection or analysis of the “observed,” or if the video was collected or included for artistic purposes.

We believe this improved our practice as researchers in that we were more mindful of the research process by completing self-checks to maintain the integrity of the data. For example, the editorial decisions shifted how we approached the final reporting. We continually reflected on whether the video clip represented our analyses. Lastly, by incorporating documentary film into the research process, the manner in which the audience might interpret the data analysis also changes. No longer is the audience faced with text or numerical data printed on the pages of an academic journal for review and consideration; but with a documentary film, the audience is provided with a variety of sounds and images, shifting how the data might be analyzed or interpreted.

The print journal article has been privileged in research dissemination despite the fact that researchers can now express themselves through multiple modes that go beyond print text. The use of documentary film not only allows the researcher to use the camera to capture moments of and analyze individuals’ lives but also presents the lives in a non-traditional research format, accessible and perhaps more palatable to a wider audience than those who subscribe to academic journals. We agree with Aufderheide (2007), who argued that “a documentary film tells a story about real life, with claims to truthfulness. How to do that honestly, in good faith, is a never-ending discussion, with many answers” (p. 2). We conclude by substituting “documentary film” with “research paper.” What results is a thought-provoking connection or intersection of / between research and documentary filmmaking.

NOTES

- 1. Permissions were obtained for all who appeared in the video and for the video’s dissemination.

REFERENCES

Aufderheide, P. (2007). Documentary film: A very short introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bergman, T. (2009). Documentary film theories. In S. W. Littlejohn & K. A. Foss (Eds.), Encyclopedia of communication theory (pp. 318 – 321). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bruner, J. (1994). Acts of meaning: Four lectures on mind and culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cole, A. L., & Knowles, J. G. (2008). Arts-informed research. In J. G. Knowles & A. L. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 55-72). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denzin, N. K. (1989). Interpretive biography. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Denzin, N. K. (2003). Performance ethnography: Critical pedagogy and the politics of culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Eisner, E. W. (1997). The promise and perils of alternative forms of data representation. Educational Researcher, 26(6), 4-10.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. London, UK: Longman Publishing Group.

Glesne, C. (2010). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Hampe, B. (2007). Making documentary films and videos: A practical guide to planning, filming, and editing documentaries (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Holt Paperback.

Heider, K. G. (2006). Ethnographic film. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Hughes, J. (2013, January 15). Exploring social justice through digital literacies. [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dZOt6RDhkVY

Hughes, J. (2007). Poetry: A powerful medium for literacy and technology development. What works? Research into Practice Series [Research Monograph #7]. Retrieved from the Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat website: https://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/literacynumeracy/inspire/research/Hughes.pdf

Hughes, J. (2008a). Poetry and new media: In conversation with four poets. Language and Literacy, 10(2), 1-28.

Hughes, J. (2008b). The performative pull of research with new media. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 7(3), 16-34.

Hughes, J. & John, A. (2009). From page to digital stage: Creating digital performances of poetry. Voices From the Middle, 16(3), 15-22.

Hull, G. A., & Katz, M. (2006). Creating an agentive self: Case studies of digital storytelling. Research in the Teaching of English, 41(1), 43-81.

Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33(7), 14-26.

Madison, D. S. (2006). Staging fieldwork / Performing human rights. In D. S. Madison, & J. Hamera (Eds.), The Sage handbook of performance studies (pp. 397-418). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Petrarca, D. (2013, January 1). Coffee. Cup. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/56611736

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nichols, B. (2010). Introduction to documentary (2nd ed.). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pauwels, L. (2011). An integrated conceptual framework for visual social research. In E. Margolis & L. Pauwels (Eds.), The Sage handbook of visual research methods (pp. 3-23). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pink, S. (2012). Advances in visual methodology: An introduction. In S. Pink (Ed.), Advances in visual methodology (pp. 3-17). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ruby, J. (2008). A future for ethnographic film? Journal of Film and Video, 60(2), 5-14.

Shrum, W., Duque, R., & Brown, T. (2005). Digital video as research practice: Methodology for the millennium. Journal of Research Practice, 1(1), Article M4. Retrieved from http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/6/12

Stake (2000). Van Maanen, J. (1988). Tales of the field: On writing ethnography. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Vaughan, J. (2013). Technological innovation in libraries: Perceptions and definitions. Library Technology Reports, 49(7), 10–17.

Weber, S. (2008). Visual images in research. In J. G. Knowles, & A. L. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 41-53). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.