Qallunaaliaqtut: Inuit Students’ Experiences of Postsecondary Education in the South

The complex and interconnected political and economic challenges facing the four regions of Inuit Nunangat,1 including the staffing and running of relatively new Northern governments, pressing social and environmental policy issues,2 and an increasing focus on non-renewable resource development in the Arctic require creative and innovative solutions, beginning with the people who call the region home.3 Having equitable access to the full spectrum of educational opportunities that support the self-determined policy and development objectives of Inuit communities and their governments is critical. In this context, the absence of an accessible university-level post-secondary institution in the Canadian Arctic is disquieting (Poelzer, 2009).

Since the mid-1980s, Inuit students from Nunavut, Labrador, and the Northwest Territories have had access to post-secondary education in their home communities through territorial and regional college systems, offering a range of post-secondary and trades programs geared primarily towards labour market needs. In Nunavik, no such colleges exist, thus, students who wish to pursue post-secondary education must do so by distance or must leave their region.

Under these circumstances, it should not be surprising that access to post-secondary education is a concern across Inuit Nunangat. Since 1981, high school and college completion levels have risen (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami & Research and Analysis Directorate, 2006); however, the percentage of Inuit who have completed a university degree has remained quite low (from 1.6% in 1981 to 2.7% in 2006). More significantly, the gap between non-Inuit and Inuit has widened since the percentage of non-Inuit who have completed a university degree has increased from 6.4% in 1981 to 16.5% in 2006 (Penney, 2009; Richards, 2008).

The lack of improvement in university level attendance and completion rates may be explained by a number of interrelated factors rooted in the legacies of state-imposed residential and federal day schools (Berger, 2001; Hicks, 2005; McGregor, 2012a, 2013) and significant differences between Inuit and Euro-Canadian educational philosophies (Rasmussen, 2001). The quality of high school education in Inuit Nunangat (Hicks 2005), a lack of relevant curriculum that recognizes and incorporates Inuit language and culture (Poelzer, 2009), and the absence of a university in the North are also factors contributing to low university participation rates.

Silta Associates (2007) concluded that university participation rates would be higher if “programs [were] developed, delivered and administered by Inuit educators or non-Inuit who have lived and taught successfully in Inuit communities, and who support student-centered learning and understand the nature of Inuit education and culture” (p. 25). They also highlight the importance of accessible funding.

Although every Inuit region in Canada has regained control of education (Nunavik in 1978, the Inuvialuit Settlement Region in 1990, Nunavut in 1999, and Nunatsiavut in 2005), a great deal of work is needed in order to develop education systems that reflect the needs and priorities of Inuit communities and citizens (Daveluy, 2009; McGregor, 2010, 2011, 2012a, 2012b, 2013). In recent years, education has become a focal point in policy and development discussions across the North, and initiatives have been undertaken by Northern governments, Inuit leaders, and educators to improve access to post-secondary education and to adapt education systems to reflect Inuit culture and objectives.4

In order to support these efforts further, it is important for decision makers and educators to have access to research on the experiences of Inuit students in post-secondary programs. Research on the factors contributing to post-secondary success in the North (see Silta Associates, 2007, for one study) and elsewhere in Canada (see Parent, 2014, for a study about the high school to university transition of Aboriginal people5) is limited. At present, very little statistical data or analysis on Inuit participation in post-secondary programs is available (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2008; Lewthwaite & McMillan, 2010).

The objective of this paper is to address this knowledge gap by presenting and discussing the results obtained during the first two years of the ArcticNet-funded project Improving Access to University Education in the Canadian Arctic (2010-2015). We will begin by explaining the origins, purpose, and methodology of the project, followed by a summary of results. In particular, we focus on issues related to language fluency, reasons for pursuing post-secondary education, preparing for post-secondary education, and the difference between post-secondary experience in the South and in the North. We will conclude with a brief discussion of possible actions for improving access to university education in Inuit Nunangat.

methodology

The research team was composed of both Inuit researchers and Southern-based researchers with long experiences working with Inuit and in Inuit Nunangat. The project stemmed from conversations with former Inuit students who had experienced difficulties finding adequate post-secondary programs when they were looking to pursue post-secondary education.

Data for this project were gathered through surveys, interviews, and focus groups. The interviews and focus groups provided qualitative data that complemented the quantitative data collected through the surveys. In total, 68 surveys were administered with current and former Inuit post-secondary students from different institutional settings: (1) three programs designed for Inuit students (the Nunavut Certificate offered by Carleton University, Nunavut Sivuniksavut, and the Master’s in Education at the University of Prince Edward Island [UPEI]); (2) one program (CEGEP Marie-Victorin in Montréal) where Nunavik Inuit students have some classes on their own but are otherwise mixed with the general student population; and finally, (3) students attending regular university programs (Carleton University and University of Ottawa) without special courses but with some additional support.

We decided to survey participants who, in addition to having pursued post-secondary in the North, had also attended programs outside of Inuit Nunangat, thus allowing us to compare their experiences. The Southern programs were chosen to encompass a good cross-section of programs attended by Inuit students.

Survey questions touched on personal motivation and goals, curriculum and program delivery, and asked participants to compare their experiences with post-secondary education in the South and in the North.6 Follow-up interviews were conducted with nine of the survey respondents.7 The interviews allowed respondents to answer in-depth questions regarding their post-secondary experiences and to elaborate on topics that were raised in the surveys. Interview participants were asked to describe their post-secondary experiences, any hardships they experienced, and challenges they had to overcome, as well as the benefits and opportunities they gained from this.

Three focus groups were organized with former Inuit students to aid in interpretation of the survey and interview data. The first took place in Iqaluit, Nunavut during Nunavut Sivuniksavut’s 25th anniversary reunion celebrations (June 2010). The second was organized during the National Inuit Youth and Elder Summit in Inuvik, Northwest Territories (August 2010), and finally, the third was organized with Saputiit Youth Association and took place in Kuujjuaq (March 2011). In addition to helping the research team understand our results, these focus groups gave participants an opportunity to share and learn from one another’s personal experiences.

This survey sample is relatively small but the follow-up interviews and the focus groups have allowed us to corroborate and refine the findings from the survey. However, since only students with experience in post-secondary education in the South were interviewed, our conclusion should not be extended to Inuit students who have only experienced post-secondary education in the North.

Two workshops were also organized: the first, held in Ottawa in March 2011, gathered stakeholders and Inuit students, plus Southern and Northern educators with experience in post-secondary education in Inuit Nunangat. Participants were asked to share their experiences about post-secondary programs (Rodon, Lachapelle, & Ruston, 2011). In November 2011, a second workshop was organized in Kuujjuaq with Nunavut and Nunavik stakeholders to explore post-secondary program delivery in the Eastern Arctic (Nunavik and Nunavut) and the creation of a university in the North (Rodon & Lévesque, 2012). During these workshops, the survey’s preliminary results were presented and discussed, and participants contributed to the interpretation of the data collected.

What have we learned?

Demographics and education history

Many respondents had participated in more than one post-secondary program prior to the ones listed in Table 1, which shows the distribution of survey respondents.

Table 1. Distribution of respondents

|

Program |

Frequency |

% |

|

Nunavut Certificate |

7 |

10.3 |

|

Nunavut Sivuniksavut |

44 |

64.7 |

|

UPEI Masters of Education |

3 |

4.4 |

|

Carleton / U of Ottawa |

3 |

4.4 |

|

CEGEP, Kativik School Board (KSB) |

11 |

16.2 |

|

Total |

68 |

100.0 |

Seventy-nine percent of respondents were female. The vast majority of them — also 79% — were between 17 and 25 years old when they pursued their post-secondary programs. The majority (62%) of respondents came from Nunavut, 15% from Nunavik, and the remaining from larger centres such as Yellowknife and Ottawa.

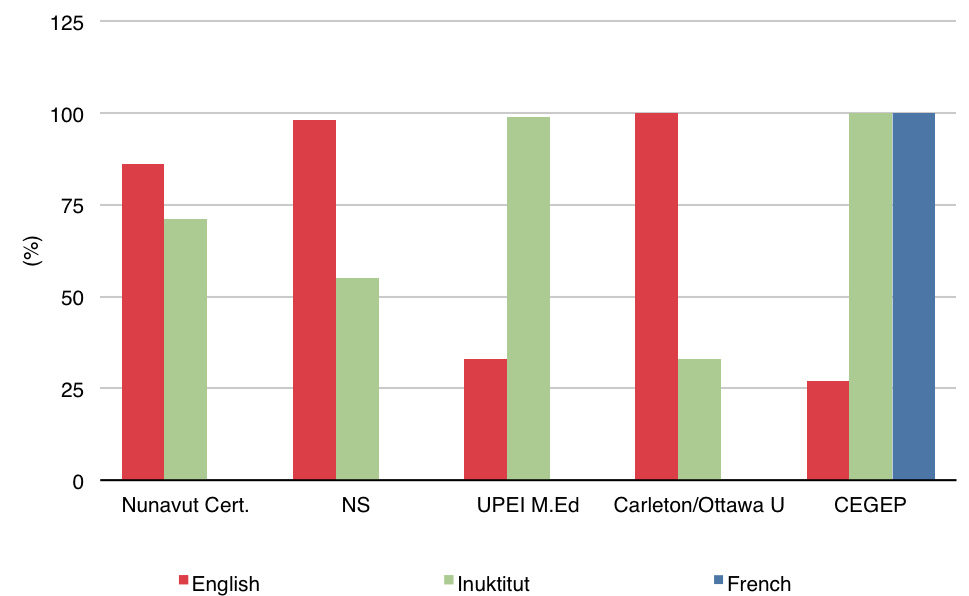

English was spoken fluently by 82% of respondents, and 60% said they were fluent in Inuktitut. The language fluency of Inuit students in different programs varied and this variability likely affected perceptions of the importance of the Inuktitut language, as will be discussed below. For example, close to 100% of former Nunavut Sivuniksavut students reported they spoke English fluently compared to 27% of UPEI students. However, all CEGEP-KSB and UPEI students said they were fluent in Inuktitut, compared to 55% of former Nunavut Sivuniksavut students. Figure 1 summarizes language fluency by program.

Figure 1. Language fluency by program

Notably, 96% of respondents reported that they had completed high school, which is significantly higher than the territorial figures for Nunavut and Nunavik. For example, in 2011, about 67% of Inuit in Nunavut had not completed high school (Statistics Canada, 2013). As of 2004, 54% of Nunavik Inuit had no high school diploma (Duhaime, 2004, p. 11). High school completion rates were well over 85% across all programs in our study with the exception of the UPEI M.Ed students, which stood at 67%. The lower rate of high school completion may be attributed to the fact that the Master’s in Education is offered by experienced Inuit educators and administrators who obtained their teaching credentials (Northern / Nunavut Teaching Education Program and Bachelor of Education) but may not necessarily have completed high school.

Forty-one percent of respondents reported that they were the first members of their family to pursue post-secondary education. Close to 81% of respondents had completed at least one certificate, diploma, or degree. Seven respondents who had not yet obtained a certificate, diploma, or degree were still enrolled in post-secondary programs at the time of the survey.

Altogether, respondents reported having pursued 46 different courses and/or programs in various CEGEPs, colleges, vocational institutes, and universities prior to the current one. Programs undertaken were incredibly diverse. For example, seven respondents took management studies at college, two pursued a hair styling / esthetics program in a vocational school, one started a BA in English and History, three more took the Nunavut Teacher Education Program, and two undertook the Intégration et exploration — Inuit at CEGEP.

Survey respondents attended post-secondary courses and/or programs at twenty-five different institutions, located in fifteen different towns and cities across Canada. One respondent also attended an international university. The majority (52%) of students took the course or program onsite, with the remaining taking their course online, or in a combination of the two.

Educational objectives

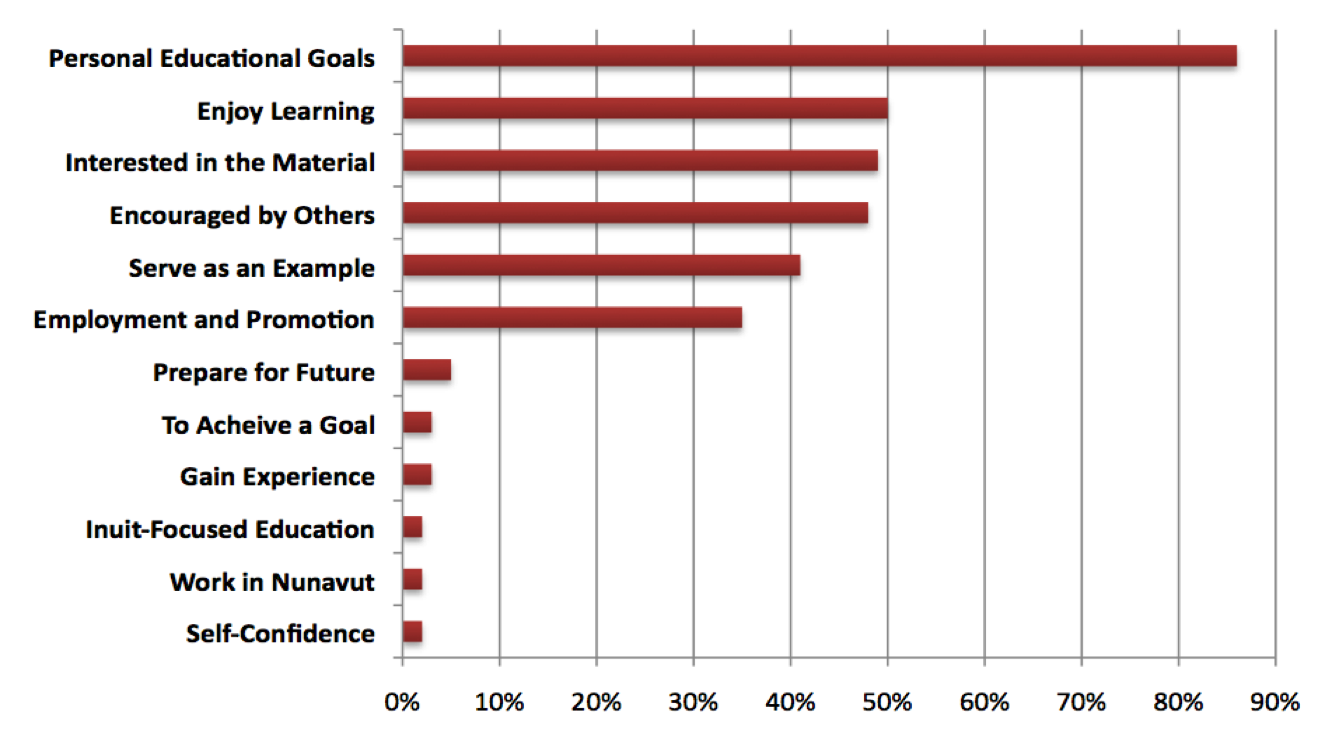

Respondents were given a list of reasons they could choose from as to why they decided to pursue post-secondary education. While some indicated they took classes because they were encouraged by their peers, others identified an interest in the material, enjoying going to school, wanting to serve as an example for others, or wanting to obtain a promotion or a better job. However, respondents overwhelmingly answered that their main motivation was to achieve personal educational goals. The most common of the educational goals identified was to “complete a university program,” followed by “training toward employment,” “act as a leader or mentor for others,” and lastly, “register for more university courses.” It is noteworthy that one third of respondents pursued post-secondary courses or programs because they were made available by their employers. Figure 2 summarizes the reasons why respondents decided to pursue post-secondary education and the educational goals they wanted to achieve.

Figure 2. Personal and educational goals

All Nunavut Certificate students cited personal educational goals as the primary reason for undertaking the program. All of the other reasons were deemed considerably less important, with serve as an example to others and interested in the material being the least important. Well over three quarters of Nunavut Sivuniksavut respondents cited personal educational goals as the primary reason for taking a course. Interest in the material and enjoy learning were given as the second and third most important reasons. Employment or promotion were seen as a reason to take a course by only a third of respondents. Carleton and University of Ottawa students reported that personal education goals, enjoy learning, and an interest in the material were the top three reasons they chose to pursue further education. Kativik School Board students offered more varied responses to the question. Of all the groups, they had the highest percentage of respondents who said they pursued post-secondary education to secure a job or obtain a promotion.

During focus groups, students identified similar educational objectives. One student said that she wanted to pursue post-secondary education “to have a positive impact” and to “contribute to decisions that affect the community” (12462-12704).7 Listening to the advice of their parents was also a motivation for many Inuit students. Only one said that the reason he was studying was because “you can’t get a job otherwise” (6441-6673). These findings suggest that the decision to attend post-secondary comes from a combination of personal motivation and support from others (family members, employers, etc.).

Preparing for and accessing post-secondary education

Respondents were asked to identify some of the elements they feel helped them prepare for post-secondary education, based on their personal experience and the experience of others they know. The top six elements (cited by at least 40% of respondents) identified were:

- 1. Strong support by others (74%)

- 2. Strong interest in course material (66%)

- 3. Relevant work / life experience (61%)

- 4. Strong high school background (57%)

- 5. Knowledge of classmates (44%)

- 6. Incorporation of cultural values (41%).

They were also asked to identify the factors that they felt impacted Inuit Nunangat-based learners’ access to post-secondary courses or programs. The top six factors (cited by at least 40% of respondents) were:

- 1. Motivation (79%)

- 2. Level of Education (74%)

- 3. Personal responsibilities (67%)

- 4. Personal preparedness (61%)

- 5. Cost (42%)

- 6. Technology (40%).

These responses highlight the relationship between student preparation for and access to post-secondary education. The most obvious example is the relationship between strong support and personal motivation. Support is one of the key factors contributing to the success of post-secondary students. Level of education obtained was cited as the second most important factor impacting access to post-secondary education. Over half of respondents reported that a strong high school background is important to prepare students for post-secondary studies. Yet, many participants also said during focus groups they did not feel Northern high schools prepared them well for the challenges awaiting them during their post-secondary courses. The fact that the “educational level in secondary school [in the North] is not to the same standards to what is offered in the South” (6636-6671) is a concern, said one participant. The same participant said that “when [Inuit students] arrive here, they have to deal with factors of moving to the city, adapting to this new pace of life and infrastructure — it’s such a different world down here. They have to catch up on top of that for their education and preparedness, and I think that’s a pretty significant aspect of determining whether they will succeed and goes into those other things: preparedness, motivation, and language” (6636-8063).

Previous work and life experience were also considered important to prepare students for post-secondary education. This might be explained by the fact that for Inuit-Nunangat students, pursuing post-secondary education is more than just going to school. It often requires that students make dramatic changes to their lives, including moving away from home, leaving relatives and friends behind, and adapting to a new cultural environment. In that context, it is not hard to understand why having work and life experience and being as prepared as possible to go through these changes is a factor that impacts students’ access to college or university.

Post-secondary experiences

Despite these challenges, the majority (86%) of respondents reported that their experience with post-secondary education was generally positive.

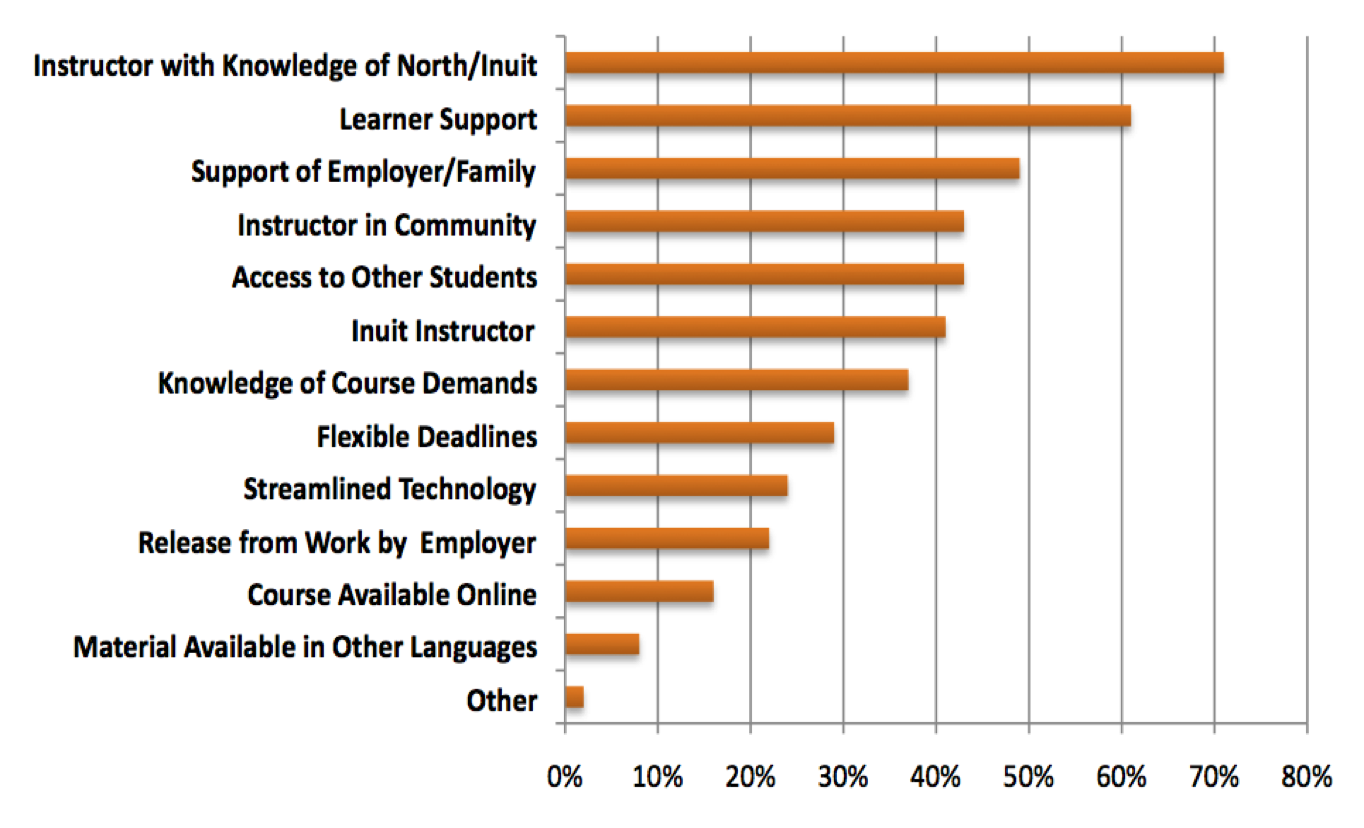

Survey respondents were asked what they valued most in their educational experience. Overwhelmingly, respondents reported that having an instructor with knowledge of the North was important, whether he or she were Inuit or not. Community-based and/or Inuit instructors were also seen as important, as well as having access to other students with whom to share the experience, and to work through the course material. Student support — including academic, family, and employer support — was another crucial element valued by respondents. Although language did not feature at the top of this list, it is important to mention, as we will see below that 72% of survey respondents reported it was “extremely important” that Inuktitut be included in courses offered to Inuit students. Figure 3 summarizes these results.

Figure 3. Valued elements of learners

During the workshop discussions, similar themes were examined. Kuujjuaq workshop participants discussed the importance of having instructors who were accustomed to, or ready to learn about the North and Inuit culture and language. Two former students of the Akitisiraq Law School, which operated in Iqaluit between 2001 and 2005, mentioned that their experience was positive because their instructors, most of whom came from Southern universities, were dedicated to learning Inuit customs and adapted their teaching material and style to make more relevant for Inuit students. Kuujjuaq workshop participants also discussed the importance of having support, which might come in many forms: the program itself can offer support through its instructors or through personnel whose work it is to facilitate the adaptation of Inuit students. But participants also said that having the support of their families and of their fellow students was particularly significant since it gave them confidence.

Workshop participants also mentioned that they put great value on having programs more relevant to Inuit students — those that include Inuit content and those that allow more flexibility in the schedule and in the types of evaluations. A workshop participant said that this was important because “when mainstream ways of doing things are imposed, it generally doesn’t work out well.” Programs that have been adapted to Inuit needs like the Akitisiraq Law School, UPEI M.Ed., Nunavut Sivuniksavut or the Certificate in Nunavut Public Service Studies at Carleton University, and the Nunavut Teacher Education Program (NTEP) at Nunavut Arctic College have seen a great many of their students graduate.

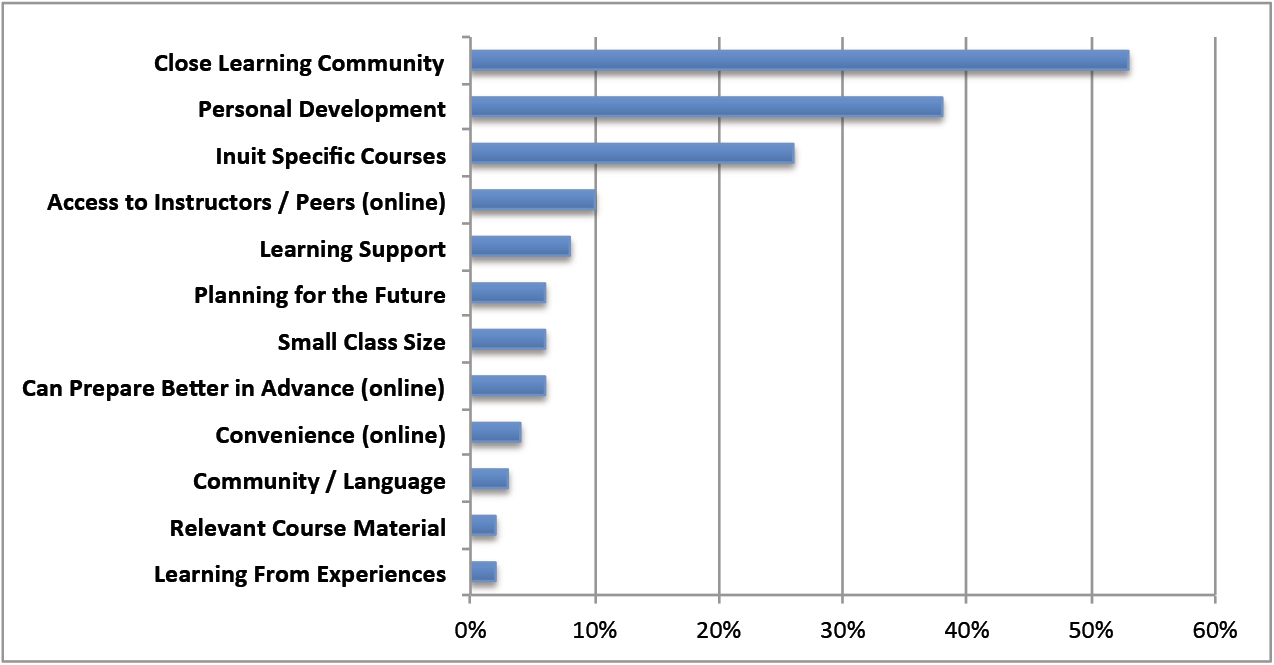

Students identified other factors they felt were integral to their success. For example, 53% participants mentioned that being part of a close learning community contributed positively to their experience. Figure 4 summarizes the factors contributing to program success.

Figure 4. Factors contributing to program success

During the Ottawa workshop, participants said that being part of such a close learning community was essential to their success. Two participants said that this allowed them to build relationships with people who could relate to their experiences. Another one added that it reduced cultural displacement by allowing them to speak their own language, to study together, and to live according to their own values. In short, they said being part of a close learning community increased their confidence and their likelihood of success. A participant in the Ottawa workshop who studied by herself at McGill University said that she felt isolated, especially because her husband and child remained behind in the North. The isolation she experienced nearly caused her to abandon her studies and return home. Therefore, the success of Inuit students seems to increase when they are part of programs attended by other Inuit, but is made more difficult when they take programs in which they may not have Inuit peers.

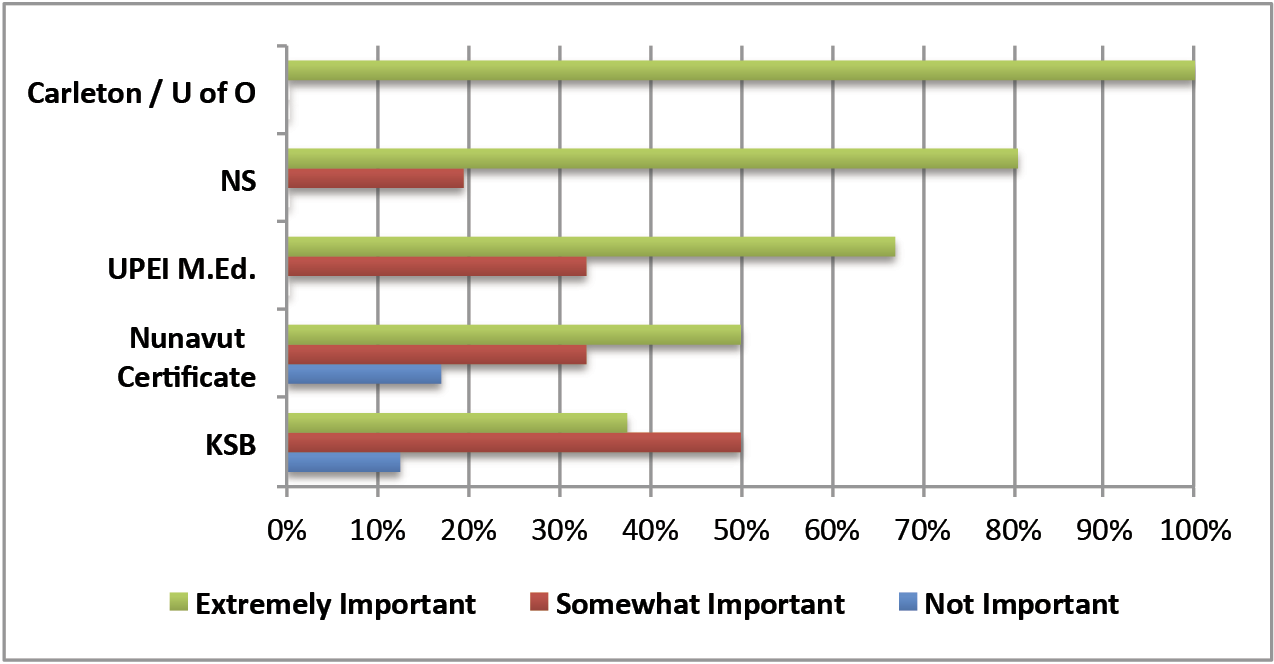

Thirty-eight percent of respondents mentioned that one of the most important contributing factors to the success of a program was the personal development and growth they could achieve while attending it. Moreover, 26% of survey respondents said that learning about their own culture and history was rewarding and contributed to their personal development. Inuit-specific courses were particularly important to Carleton and Ottawa University students, yet they were not deemed important by any of the Kativik School Board students surveyed. Similarly, respondents were asked to rank the importance and use of Inuit languages (Inuktitut or Inuttitut) in their post-secondary courses or programs, and to assess the impact that use (or lack thereof) of Inuit languages had on their learning experience. The incorporation of Inuit languages in post-secondary curricula was at least somewhat important to 97% of respondents. The majority (72%) considered it to be extremely important. Again, there was a marked difference between programs. While 81% of Nunavut Sivuniksavut students reported that it was extremely important for them that programs incorporate Inuit language, only one Kativik School Board student felt this way. Students from the Nunavut Certificate program had the highest percentage of respondents who reported that the use of Inuktitut in post-secondary programs is not important. Figure 5 summarizes the perceived importance of Inuit languages in course delivery, by program.

Figure 5. Importance of Inuit languages in course delivery, by program

The difference between programs concerning Inuit-specific courses and the incorporation of Inuit languages into the curricula may seem striking at first but can be explained by the educational objectives and cultural background of students attending the programs. Students taking the Nunavut certificate are Government of Nunavut employees who want to learn more about public administration. Their primary objective is professional development leading to a promotion or a new job. Kativik School Board students come from an environment where Inuktitut is widely spoken and traditional economic activities are important. All of them are fluent in Inuktitut and might not feel the need to attend courses in that language. Also, as mentioned above, of all the students who participated in this project, the highest percentage of respondents who said they pursued post-secondary education to secure a job or obtain a promotion were from the Kativik School Board. Students attending other programs like Nunavut Sivuniksavut or those studying at the Universities of Ottawa or Carleton tend to be younger, are not as fluent in Inuktitut, and are not as focused on pursuing further education for the purpose of obtaining a promotion or a job.

Although respondents reported the use of Inuktitut to be important, 64% of respondents reported that Inuit languages were rarely or never used in their post-secondary classes (0 to 25% of the time). According to 16% of respondents, Inuit languages were used up to 50% of the time, while seven percent reported use between 50% and 75% of the time. Only 11% said Inuit languages were used more than three quarters of the time. The main ways in which Inuktitut was incorporated into the courses were through instructors, assignments, elders, guest speakers, course texts, and lectures.

Respondents were also asked to assess the impact that the use of English or French as the primary language of instruction had or has on their learning experience. Nearly three-quarters reported that they were positively impacted by the use of English or French as the primary language of instruction. Respondents explained that even though the incorporation of Inuit languages is important to their learning experience and contributes to their success, they were not negatively impacted by having English or French as the primary language of instruction for three main reasons: they felt they were fluent enough in English (36%), that English is easier to understand (24%),9 and that knowing English or French is important or necessary (21%).

Comparing Northern and Southern-based post-secondary education

Participants were asked to compare the advantages and disadvantages of attending post-secondary in the North and in the South. They said that the advantages of a Northern-based post-secondary education were that it allowed them to remain in a familiar environment with access to important cultural activities and practices, maintain easy access to a network of people who offer support, live close to relatives, be in classes with few students, learn in Inuktitut, and have access to Arctic foods (i.e. seal, caribou, Arctic char, etc.). The disadvantages mentioned were the limited program options, the lack of academic challenges, the lack of facilities, the difficulties of finding adequate housing, and the high cost of living.

The perceived advantages of a Southern-based post-secondary education were that Inuit students could learn to be independent; experience new things; have access to more amenities, activities, resources, and facilities; and meet new people. Many also said that they appreciated the larger number of programs and courses. However, many said that moving away from the North to study in the South, and learning to live in a new environment without appropriate support was extremely challenging. Some of the reported disadvantages of a Southern-based education included: the lack of a support network; lack of access to Inuit-language speakers, cultural practices, and country foods; leaving relatives behind; feeling isolated; and having to manage personal finances. Adapting to higher education standards and overcoming the latent institutional racism were also identified as important challenges by several workshop participants (Rodon & Lévesque, 2012). Big classes and the irrelevance of certain aspects of course curriculum were also considered problematic. The lack of learner support specifically geared to Inuit was also identified by several participants, who said Northern students needed support programs to succeed such as workshops, tutors, instructors with knowledge of the North, as well as support for relatives who stayed in the North. Table 2 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of a Northern and a Southern-based education.

Table 2. Northern- and Southern-based post-secondary education (PSE): Advantages and disadvantages

|

|

Northern-based PSE |

Southern-based PSE |

|

Advantages |

Close to home and family / friends Access to land and country food In a familiar environment Close to community / Support network Easier to identify with people and society |

Learning independence Experience something new More amenities and activities More resources / better facilities Meet new and different people / build relationships |

|

Disadvantages |

Limited resources and options Lack of facilities Might not leave home and experience new things High cost of living Community / family obligations and distractions |

Far from home Away from family / friends Disconnected from the land Disconnected from Inuit and Inuit culture Homesickness |

It is worth noting that the elements identified by respondents are mostly symmetrical. That is, Northern-based education advantages are symmetrically opposed to Southern-based education disadvantages, and vice-versa, suggesting that there are significant trade-offs involved in decisions regarding post-secondary education for Inuit students.

Preferred course delivery methods

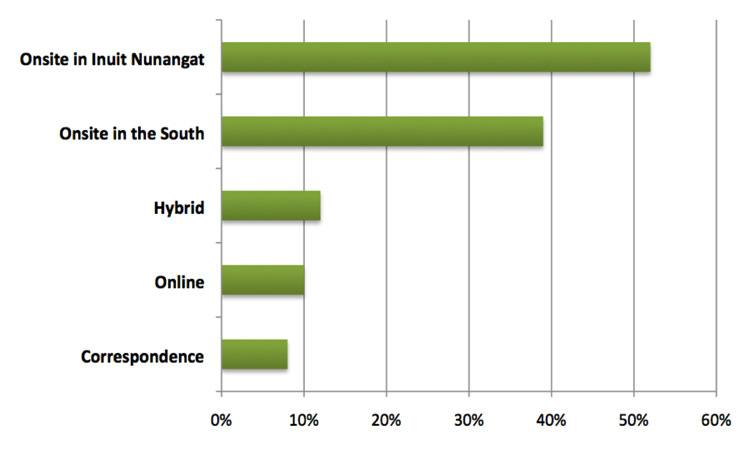

Respondents were asked to rank their preferences with respect to methods of course delivery. The results displayed in Figure 6 are based on the number of times a delivery method was selected as a first choice.

Figure 6. Ranking of course delivery preferences

Clearly, onsite delivery is the preferred method of course delivery, with more respondents choosing an Inuit Nunangat-based course, followed by one delivered onsite in the South. Despite the findings reported above that many respondents perceive attending post-secondary in the North to be a disadvantage, it is obvious that many would still prefer to remain in the North given the choice. Most students would prefer not to leave home and be separated from their support networks. Interestingly though, respondents preferred courses delivered onsite in the South to online courses they could take from their homes in the Arctic. This makes sense given the importance respondents placed on academic and personal support. Programs delivered onsite in the South that are designed specifically for Inuit students tend to operate on the cohort model, meaning a group of Inuit students will study together for the duration of the program and will thus benefit from the support of their peers. Nunavut Sivuniksavut, UPEI Nunavut Master of Education, and the Akitsiraq Law School are examples of programs that have been successful using this approach. Online programs do not offer this kind of support, and are seldom adapted to Inuit and Northern realities. Internet connectivity and bandwidth limitations in the North make distance education even more challenging.

Other challenges

During workshops, interviews, and focus groups, participants identified three challenges that affected their post-secondary education, which were not identified by the surveys. These are summarized here.

First, many students who undertake post-secondary education are parents with young children. For those who must leave their home communities for larger centres in the North (i.e. Yellowknife or Iqaluit) or cities in the South (i.e. Edmonton, Ottawa, or Montreal), this proved to be extremely challenging. Even students who studied in their home communities and had their children with them felt it was challenging to balance family life with academic studies. They all said that they needed extra support from their families to complete their studies.

Second, the challenge of finding housing both in the North and in the South was raised by participants. In the North, although there are a limited number of housing units available for students and their families, this number is not sufficient. Many students do not have access to these units and must find other accommodations. As one participant noted, “when you have a child, it’s difficult to share a room with another student” (12972-12074). Students who are not married and/or do not have children do not have access to priority housing. Moreover, they do not have access to subsidies, so even if they can find a vacant unit, they have to pay market rent, which is often well above $2,000 per month. The only way for students to pay such high rent is to find work, which can be detrimental to their academic success. Those who live in public housing encounter other kinds of problems. For example, public housing policies stipulate that residents must give up their unit if they move out of their community to go back to school, which means they have nowhere to go when they graduate and move back. One participant explained that he felt he had to choose whether to “give up an education for [his] home or give up [his] home for education” (13120-13434). This is a common problem, especially in Nunavut, where 57% of the population occupies public housing (Nunavut Housing Corporation, 2012). Students pursuing post-secondary education in the South also face housing issues. There is limited non-profit housing for Inuit in Southern cities, so they must either stay in student residences or rent rooms or apartments off campus. The costs associated with these options are often prohibitive for those students relying primarily on funding to cover their tuition and living expenses.

Finally, funding has proven to be a constant concern among students. Participants discussed the lack of funds they are able to access, the inequity and inconsistency of funding opportunities between Arctic regions, and the difficulties associated with applying for funding. Many said that student loans were insufficient and made it difficult to make ends meet. Others mentioned it was nearly impossible for them to travel back home during the holidays to see their relatives and friends. Most felt loans were not sufficient to cover expenses, and thus they needed to find work, which might jeopardize their academic success. Other students experienced cuts to their funding when they reduced their course load either because they felt they could not succeed in a course, or to accommodate their work schedule. Not all students said funds were insufficient, however. At least one said that “definitely government should try to show more support,” but that Inuit tend to think that “government should sort of be there for us and give everything on a silver platter” (13528-15001).

Depending on where they are from, Inuit students have access to different funding programs. Because of this, students from certain regions have better funding than others, which creates inequalities among Inuit students. Students from the Kativik School Board said they received significant financial support throughout their studies (2965-3117). In Nunavut, some students said it was unfair that FANS, Nunavut’s Student Financial Assistance Program, gave the same amount of money for everyone, even those who resided where the cost of living was higher (25991-26072). In the Northwest Territories, students get only $700 a month, which barely covers the cost of an apartment and forces them to find part-time jobs. This, coupled with a cap on earning for those with funding, makes it difficult for students to meet even the most basic financial obligations (9701-9975). It should also be noted that all three university programs delivered in Nunavut were fully paid by the governments (Federal and/or Government of Nunavut) and involved no cost for the students.

DISCUSSION

This research identifies many issues faced by Inuit post-secondary students. Access is a significant problem. Not only do many Inuit students feel that their high school education did not prepare them adequately for post-secondary education but also that, even after they graduate, their options for post-secondary education are limited. The fact that there is no university in Inuit Nunangat means that post-secondary students either have to choose among the limited number of vocational programs at one of the Northern colleges or move away from the North to study in a Southern college or university, where more options are available but where they face other barriers and challenges. Furthermore, Southern universities seldom offer programs adapted to Inuit culture and needs. Courses do not necessarily have a Northern focus and are not taught in Inuktitut, two elements identified as particularly important by participants. Our research suggests that most Inuit students do not study in order to prepare for future careers or to meet the needs of the Arctic job market. They pursue post-secondary education to achieve personal goals, because they enjoy learning, they want to become role models and contribute to their communities, and they are looking to improve their academic and life skills.

This research shows that post-secondary education is often an all-encompassing experience for many Inuit students, academically, socially, and culturally. For this reason, as participants highlighted, academic and social supports are crucial for achieving success. Students benefit from counselling and orientation, but they also need support from their instructors and classmates, and from their family and friends. It has been shown that the cohort model used by Nunavut Sivuniksavut and the UPEI Masters of Education, where many Inuit students undertake the same program at the same time, is successful because it allows students to support each other on both a personal and academic level.

Inuit post-secondary students also face other issues. For example, the availability of housing is a determining factor when students make decisions about where to pursue post-secondary education. A lack of student specific housing means that many Nunavut students must work to cover their expenses, putting a strain on their academic pursuits. Funding is also an issue, since not all Inuit have access to the same funding programs, and funding arrangements can be inconsistent and tenuous. While some funding programs are more generous than others, none of the students said their funding covered their needs.

Students and educators have identified several solutions to make post-secondary education more sustainable and better adapted to Inuit needs and desires. First, program design and delivery should be more reflective of Inuit realities. This would mean developing programs in partnership with students. These programs might focus on Inuktitut, be field-based, or include Inuit elders, for example. Continuous research and evaluations of teachers, educators, and programs are also needed to ensure the quality of programs remains consistent and that the programs are meeting students’ needs.

Given the importance of family support for student success, a strategy should be put in place to encourage parents to support their children in their educational pursuits. The difficult historical relationship between Indigenous peoples and the formal education system in Northern Canada cannot be forgotten or erased but contemporary efforts to make post-secondary education more accessible to Indigenous students through the involvement of Inuit communities, leaders, students, and educators in designing and carrying out education programs are important steps upon which we can build.

Funding opportunities should be adapted to reflect the particular needs of Northern students. Participants noted the difficulty students have finding information related to funding and program applications, as well as other aspects of the post-secondary experience. Many participants recommended that an online portal could be a place where they could get this information. In 2013, the Tukiktaarvik Inuit Student Centre was launched to respond to this need for increased access to information about post-secondary education. Tukitaarvik creates an online community of current, former, and prospective students across Inuit Nunangat. As a member of the Tukitaarvik community, one can learn about post-secondary programs, access a handbook for post-secondary students, and connect with other students and mentors. This is an important development in helping to improve access to post-secondary education, but it is just the beginning.10

CONCLUSION

This research shows that in spite of the numerous challenges associated with pursuing post-secondary education in the South, most Inuit students who participated in this study considered their experience to be positive, this is particularly true for those who attended Nunavut Sivuniksavut and the UPEI Master’s in Education. Three of the most important elements contributing to their positive experience were the incorporation of Inuit language and culture, the availability of instructors who are familiar with the North, and access to academic and personal supports. These findings corroborate other research concerning Inuit post-secondary education (Poelzer, 2009; Silta Associates, 2007). Lack of access to sufficient and equitable funding was perceived by participants to be a significant barrier, as was the lack of readily available information for prospective students from Inuit Nunangat.

While the 2006 Conciliator’s Final Report (Berger, 2006) points to education as a key element in the success of the Nunavut government, this conclusion can be applied to all Inuit regions, where education levels remain very low relative to the rest of Canada. In Inuit Nunangat, the university education “deficit” is growing despite a steady increase in Inuit students attending universities. In fact, the gap between Inuit and the rest of Canadians in terms of university completion is widening. The explanations for this gap are manifold: the impact of residential schools and the colonial roots of the public education system, lack of funding, uneven quality of schooling, and the absence of a university in Inuit Nunangat, to name a few. Under the pressure of resource development, Northern governments are choosing to emphasize training for the short-term needs of the job market, often at the expense of longer-term social and economic development objectives for the North (Sabin & Kennedy, 2012). Given the link between education and political development, improving access to post-secondary education is a critical issue for northern and Inuit governments to address. The federal government has a clear fiduciary responsibility to invest more in education and an Arctic university would be a good starting point. Our research shows that students want more access to post-secondary education, not only training, in order to have the same opportunities as the rest of Canadians.11 For now though, this is not the case.

NOTES

1. Inuit Nunangat refers to the four Inuit regions of Canada: the Inuvialuit Region in the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Nunavik in Arctic Quebec, and Nunatsiavut in Labrador.

2. For example, suicide, housing, healthcare delivery and cost, low level of education, high unemployment, preservation of Inuit language and culture, climate change, and resource development.

3. The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of Melissa Ruston and Marise Lachapelle, who provided expert research assistance for this project. We want to thank the Inuit students who agreed to participate in the survey. Finally, we also wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers who offered both critical and constructive advice, thus contributing greatly to improving this paper. However, please note that the content as well as any factual errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. This project has been funded by ArcticNet, a Network of Centres of Excellence of Canada.

4. In 2008, Nunavut adopted its Education Act (S.Nu. 2008, c.15.). See, for example, First Canadians, Canadians First: National Strategy on Inuit Education, (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, 2011), and the Northwest Territories’ Education Renewal and Innovation Framework: Directions for Change, (Department of Education, Culture, and Employment, 2013). For a collection of articles focusing on innovations in education in Inuit Nunangat, also see the special issue of Northern Public Affairs magazine (Gladstone, Kennedy Dalseg, & Sabin, 2014).

5. Parent (2014) examines four early Aboriginal university promotion initiatives and three Aboriginal university transition programs in British Columbia. Many of her conclusions are similar to those identified in this paper; for example, the need for post-secondary institutions to provide Indigenous learners with better support and resources. Parent also discusses the importance of framing transition to university in terms of self-determination and encourages universities to promote the goals of self-determination for Aboriginal students as parts of their recruitment strategies, an aspect which has not yet been analyzed in Inuit Nunangat.

6. The survey provides invaluable data but also has limitations. Sixty-five percent of survey respondents were former Nunavut Sivuniksavut students. In two of the programs, only three former students are represented (University of Prince Edward Island Masters in Education, Carleton University, and University of Ottawa). Where the findings are disaggregated by programs, care should be taken when interpreting figures for the University of Prince Edward Island, Carleton, and Ottawa university students.

7. The demographics of interviewees and focus group participants are similar to those of survey respondents. Workshop participants show a little more diversity because, apart from the past and current post-secondary students, Northern stakeholders and decision makers also attended (i.e., Kativik Regional Government, Nunavut Arctic College, Kativik School Board, Iqaluit mayor, and Kuujjuaq vice-mayor), as well as university researchers from Carleton University, Université Laval, and UPEI.

8. Interviews and focus group discussions were referenced in Dedoose to facilitate analysis. This software generates identification numbers used here to preserve participants’ anonymity.

9. This was understood by the research team to mean that different languages are more useful or appropriate in certain settings.

10. This preoccupation actually led to the creation of the web site Tukitaarvik: Inuit Student Centre (http://www.tukitaarvik.ca/). See also McAuley & Walton (2011).

11. By same opportunities, we mean equal opportunities, in the context of Inuit Nunangat. These opportunities have to take into account this specific context to provide Inuit with what they need.

REFERENCES

Berger, P. (2001). Adaptations of Euro-Canadian schools to Inuit culture in selected communities in Nunavut. (Unpublished master’s dissertation), Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, ON.

Berger, T. (2006). The Nunavut project. Conciliator’s final report: Nunavut land claims agreement implementation contract negotiations for the second planning period 2003-2013. Retrieved from https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-INTER-HQ/STAGING/texte-text/nlc_1100100030983_eng.pdf

Daveluy, M. (2009). Inuit education in Alberta and Nunavik (Canada). Études / Inuit / Studies, 33(1-2), 173-190.

Department of Education, Culture, and Employment. (2013). Education renewal and innovation framework: Directions for change. Yellowknife, NT: Government of the Northwest Territories. Retrieved from https://www.ece.gov.nt.ca/files/ERI/eri_framework_tabled.pdf

Duhaime, G. (2004). Social and economic situation of Nunavik and the future of the State. Retrieved from http://www.chaireconditionautochtone.fss.ulaval.ca/documents/pdf/108.pdf

Education Act S.Nu. 2008, s.15. Retrieved from http://www.gov.nu.ca/sites/default/files/gnjustice2/justicedocuments/Statutes/633639155154181546-353475780-e2008snc15.pdf

Gladstone, J., Kennedy Dalseg, S., & Sabin, J. (2014). Revitalizing education in Inuit Nunangat. [Special issue]. Northern Public Affairs. Retrieved from https://www.itk.ca/front-page-story/revitalizing-education-inuit-nunangat

Hicks, J. (2005). Education in the Canadian Arctic: What difference has the Nunavut government made? Indigenous Affairs, 1(5), 8-15.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2008). Report on the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami education initiative: Summary of ITK summit on Inuit education and background research. Inuvik. Retrieved from https://www.itk.ca/system/files_force/2008FinalEducationSummitReport.pdf?download=1

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. (2011). First Canadians, Canadian first. National strategy on Inuit education 2011. Retrieved from https://www.itk.ca/system/files_force/National-Strategy-on-Inuit-Education-2011_0.pdf?download=1

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, & Research and Analysis Directorate. (2006). Gains made by Inuit in formal education and school attendance, 1981-2001. Ottawa, ON: Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians.

Lewthwaite, B., & McMillan, B. (2010). ‘She can bother me and that’s because she cares’: What Inuit students say about teaching and their learning. Canadian Journal of Education, 33(1), 140-175.

McAuley, A., & Walton, F. (2011). Decolonizing cyberspace: Online support for the Nunavut M.Ed. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 12(4), 17-34.

McGregor, H. E. (2010). Inuit education and schools in the Eastern Arctic. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

McGregor, H. E. (2011). Education and schools in the Eastern Arctic. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

McGregor, H. E. (2012a). Nunavut’s Education Act: Education, legislation, and change in the Arctic. The Northern Review, 36(Fall), 27-52.

McGregor, H. E. (2012b). Curriculum change in Nunavut: Towards Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit. McGill Journal of Education, 47(3), 285-302.

McGregor, H. E. (2013). Situating Nunavut education with Indigenous education in Canada. Canadian Journal of Education, 36(2), 87-118.

Nunavut Housing Corporation. (2012). Igluliuqatigiilauqta. ‘Let’s build a home together’. Framework for the GN long-term comprehensive housing and homelessness strategy. Iqaluit, NU: Nunavut Housing Corporation.

Parent, A. (2014). Bending the box: Learning from Indigenous students transitioning from high school to university. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC.

Penney, C. (2009). Formal educational attainment of Inuit in Canada, 1981-2006. In J. P. White, J. Peters, D. Beavon, & N. Spence (Eds.), Aboriginal education: Current crisis and future alternatives. Toronto, ON: Thompson Educational Publishing.

Poelzer, G. (2009). Education: A critical foundation for a sustainable North. In F. Abele, T. Courchene, F. Seidle, & F. St-Hilaire (Eds.), Northern exposure: Peoples, powers, and prospects for Canada’s North (pp. 427-467). Montreal, QC: Institute for Research in Public Policy.

Rasmussen, D. (2001). Qallunology: A pedagogy for the oppressor. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 25(2), 105-116.

Richards, J. (2008). Closing the Aboriginal / non-Aboriginal education gaps (C.D. Howe Institute Backgrounder No. 116). Toronto, ON: C.D. Howe Institute.

Rodon T., Lachapelle, M., & Ruston, M. (2011). Improving access to university education in the Canadian Arctic: Learning from past experiences and listening to Inuit student experiences. Pan-Canadian Workshop, Carleton University, March 2011. Retrieved from http://fss.ulaval.ca/cms_recherche/upload/dev_nord/fichiers/unconference_report_light.pdf

Rodon, T., & Lévesque F. (2012). Improving access to university education in the Canadian Arctic: Learning from past experiences and listening to Inuit student experiences. Kuujjuaq Workshop November 2011. Retrieved from http://www.fss.ulaval.ca/cms_recherche/upload/dev_nord/fichiers/report_kuujjuaq_light.pdf

Sabin, J., & Kennedy, S. (2012, October). The economic legacies of colonial state institutions: Can territorial governments foster economic wellness? Paper presented at Pathways to Prosperity: Northern Governance and Economy Conference, Yellowknife, NT.

Silta Associates. (2007). Post-secondary case studies in Inuit education: A discussion paper. Ottawa, ON: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami.

Statistics Canada. (2013). Nunavut (Code 62) (table). National household survey (NHS) Aboriginal population profile. 2011 National household survey. (Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 99-011-X2011007). Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/aprof/index.cfm?Lang=E