Swerve & Shift: The Lived Experience of Canadian Faculty Teaching through a Pandemic

Maggie Mcdonnell Concordia University

ERIN REID University of Lethbridge

The evening of March 12, 2020, I [Maggie] was frantically preparing to teach a class the next morning at 8:45 a.m. The regular instructor had taken ill very suddenly, and wouldn’t be returning. We didn’t have a replacement lined up yet. As program coordinator, I was about to step in for the interim, without access to the former instructor’s lesson plans, grades, or syllabus. I was resigned to a late night and an early morning.

Then my phone rang. The department Chair was calling me… in the evening?

As of Friday, March 13, all classes and campus activities were suspended. While I was quietly relieved that I didn’t have to be awake enough to teach at 8:45 a.m. after all, I was, like so many of my colleagues, left wondering, “well, what now?”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, which began to affect Canadian universities and colleges in March 2020, teachers were asked to make a very sudden transition, or swerve, to teaching remotely. As the pandemic continued, administrations directed faculty to shift, and continue teaching online or in adapted formats throughout the fall of 2020 and winter of 2021. While these subsequent online or hybrid semesters involved a less dramatic transition, the shift was still significant, implying a steep learning curve as educators and other members of the academic community learned to navigate new or unfamiliar technology and how to recreate or replace classroom activities for the virtual classroom. This swerve and shift to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on faculty members, one that has arguably also been traumatic, producing responses of burnout and feelings of hopelessness (Brunzell et al., 2021; Gross, 2020). As educators and scholars of education ourselves, we were deeply curious about the impacts of this swerve and shift on our colleagues in higher education. We thus embarked on a research project, drawing on narrative inquiry to explore the lived experiences of faculty members during the COVID-19 pandemic. We chose this methodological approach because we sought to give participants a voice on the trauma of teaching through the pandemic along with ways they found to cope and even thrive. We first situate our study theoretically, combining Porges’ (2017) polyvagal theory of trauma with Wenger et al’s (2002) and Donaldson’s (2020) conceptualizations of communities of practice. We then present the findings from our interactive interviews, which were conducted in spring and summer of 2021, focusing on how participants’ experiences revealed traumatic elements, including dealing with emotional exhaustion, but also how their narratives involved hopeful experiences, especially through building unlooked-for communities of practice. Our aim with this research was not to propose solutions or strategies for the next emergency scenario, but rather, to make space for lived experience. Ultimately, we hope that the thoughts and experiences shared provide a source of solidarity to others who may see their own experiences, thoughts, and frustrations mirrored there. Taken together, these narratives represent threads of an ultimately collaborative experience we all shared, one that ought to be “braided or woven” so as to be used to support reflective pedagogy within communities of practice in higher education (Damiani et al., 2017, p. 675).

Trauma and Burnout

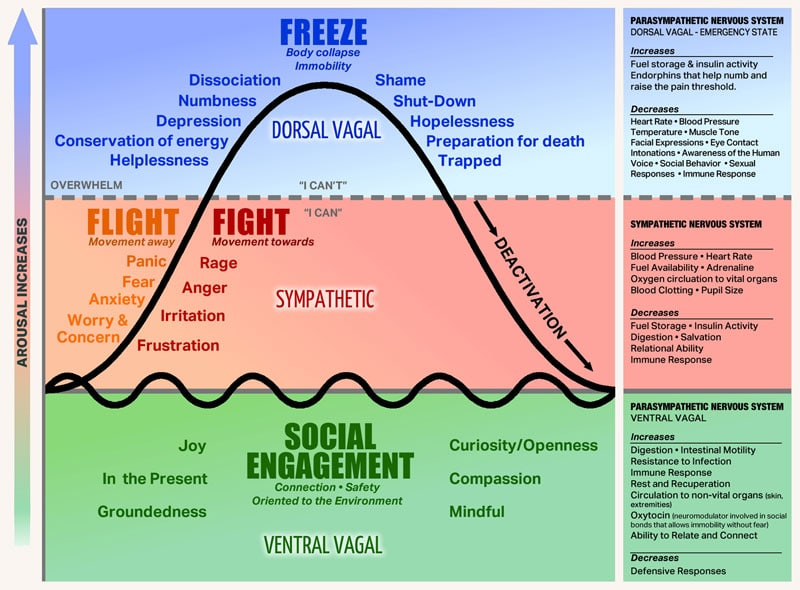

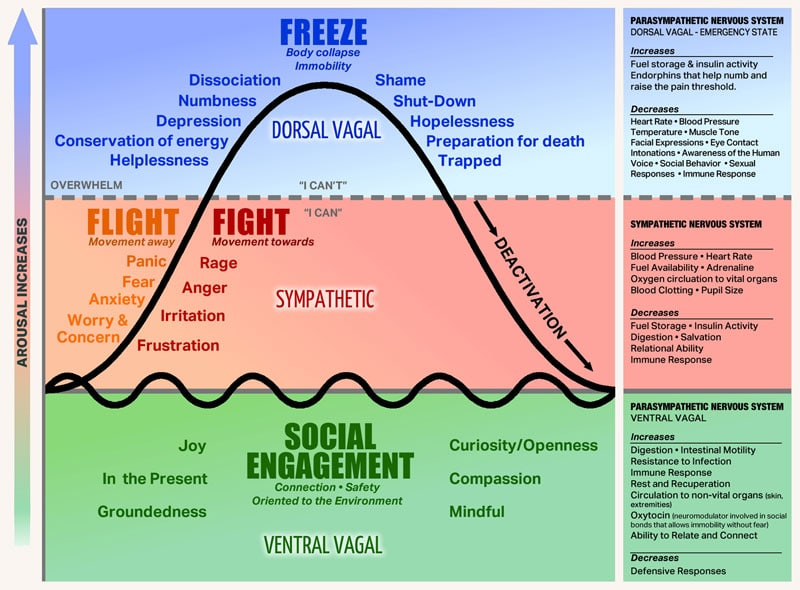

We are not the first to frame as a form of trauma the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on those tasked with teaching in educational institutions (Brunzell, T., et al., 2021; Gross, K., 2020). While educators did not face the challenges, stressors, and traumas encountered by healthcare workers during the pandemic, the everyday low-level stress of living through this global crisis resulted in a collective trauma for educators (Masiero et al., 2020). Writing from their perspectives as university lecturers, Kutza and Cornell (2021) conceptualize trauma as something that occurs not only on an individual scale but also on a societal level, noting that it creates an experience that “stirs up collective sentiment and often results in changes to culture and mass actions” (p. 14); this description aptly captures the major upheavals we have seen across institutions of higher education. As a means of understanding the impacts of trauma on behaviour, Porges (2009) helps organize our responses to trauma into three possible courses of action: to freeze, to move either away from (flight) or toward (fight) the conflict, or to connect (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Porges’ Polyvagal Theory

Note: The chart (Rankin, n.d.) illustrates the responses described in Porges’ polyvagal theory. Responses in the red and blue zones (fight, flight, or freeze) indicate states of high stress or trauma. In the green zone of social engagement, we feel connected and secure.

In Porges’ framework, the upper two levels of freeze and fight / flight descriptors correspond to many of the emotions experienced by educators during the pandemic, including burnout. For example, feelings of hopelessness, dissociation, and depression share much in common with burnout as described by Maslach et al. (2001). They write that burnout is “a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job, and is defined by the three dimensions of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy” (2001, p. 397). Indeed, this concept of burnout may also be applied as part of our multifaceted framework for conceptualizing the experiences of teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our participant responses frequently corresponded to the freeze and fight/flight stages described by Porges (2017). While flight or fight may seem oppositional, in the Porges framework, both are instances of movement; rather than being frozen, our response is to move toward or away from the stressor. While educators undoubtedly experienced various stages of trauma, it is clear that they also found ways to alleviate this trauma. For some, turning to social media, and specifically to virtual communities of practice, became a strategy to mitigate the impacts of trauma experienced in the swerve and shift to online teaching.

Communities of Practice

When we are on campus, educators participate in communities of practice without having to seek them out because such communities are organically integral to our in-person collective (Wenger 2010). These communities of practice are “so informal and so pervasive that they rarely come into explicit focus, but for the same reasons they are also quite familiar” (Wenger 2010, p. 222).

In Wenger et al’s model (2002), a community of practice is characterised by three fundamental elements: domain, community, and practice; that is, a localized group connected by a shared vocation and a shared philosophy with regard to that vocation. Wenger (2009) argued that as social creatures, we are inevitably drawn to communities of practice; our social nature is an essential aspect of teaching and learning. From a socio-constructivist understanding, we recognize ‘learning’ as a matter of engaging in the world, and ‘meaning’ in terms of how we interpret and articulate that engagement. Thus, a community of practice is at once a “privileged locus for the acquisition of knowledge” and “a good context [in which] to explore radically new insights without becoming [...] stuck” (Wenger 1998, p 214).

One of the most disruptive aspects of the sudden swerve to emergency remote teaching, one of our participants noted, was the loss of our organic community of practice, or what might otherwise be referred to as water cooler moments (McDonnell, 2022). Beginning in March 2020, educators in many fields turned to social media as a platform to support communities of practice (Aguilar et al. 2021, Chan et al. 2020, Greenhow & Galvin 2020, Hall et al. 2021, Trust et al. 2020). Even prior to the pandemic, social media was being harnessed as a means of connecting educators “for the purpose of professional learning to support pedagogical change” (Goodyear, Casey, & Kirk, 2014, p. 940). However, the sudden shift to online teaching accelerated this movement dramatically.

In response to the swerve to emergency remote teaching, Donaldson (2020) conducted an analytic literature review with the goal of determining best practices for a digital community of practice. Donaldson found that virtual communities of practice can be important support, particularly “during times of unprecedented change” (p. 248). Just as Wenger’s (1998) concept of a community of practice requires more than simply being in the same place at the same time, Donaldson’s digital community of practice requires certain characteristics beyond accessing the same social media site.

Communities of practice are dynamic entities (Wenger 2010), and digital communities of practice even more so, since members can come and go, and be more or less active. A successful community of practice thrives on a shared philosophy with regard to the common vocation, Wenger (1998) says; likewise, Donaldson (2020, p. 247) suggests, with a successful online community of practice, which needs a compelling philosophy, shared goals, community autonomy and organic growth. Donaldson further specifies that group goals, focus, and growth cannot be imposed, but can be built into the mandate of the group. Membership falls under this banner as well; a group created on Facebook may restrict and monitor membership, while an X (formerly Twitter) topic thread is more accessible and open to any other X user.

In this article, our multifaceted framework uses Porges’ framework of freeze, fight/flight, and social engagement, in combination with Wenger and Donaldson’s conceptualizations of communities of practices to contextualize our interpretations of our participant experiences teaching in higher education during a global pandemic. Specifically, we were interested in how faculty understood the role of communities of practice as a means of mitigating their own freeze and fight / flight responses.

We understand our ontological positions as educational researchers and instructors from a socio-constructivist position, whereby our research subject does not exist outside our own lived reality, but rather is “shaped by our lived experiences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2018, p. 116). We thus draw on narrative inquiry as a methodological approach because as a methodology and as a “way of understanding experience” (Clandinin 2013, p. 9), narrative inquiry allows researchers and their participants to recognize lived experience as a source of knowledge. Through this framework we aimed to understand the experiences of educators across Canada during this swerve and shift. We wanted to examine how individual educators’ stories, from the beginning, middle, and end of the COVID-19 pandemic can complement the emerging theoretical research (Mishra et al. 2020, Crawford et al. 2020, Karalis & Raikou 2020, Alhawsawi & Jawhar 2021) and policy analyses (Blankenberger & Williams 2020, Karakose 2021, El Masri & Sabzalieva 2020).

Participants

We recruited our participants through our own personal networks, engaging in what Garton and Copland (2010) describe as an “acquaintance” interview; namely, an interview in which the participants are already known to the researcher(s). This meant that there was a high degree of trust already established; as we all had lived similar experiences as professors, we already formed a sort of micro-community of practice (Dorland, et al., 2019). In most cases, recruitment was done via an email that included a brief description of the project and the details of participation. Participants needed to have been actively teaching during the initial pandemic and employed in either a university or community college in Canada. We reached out to our contacts living in various provinces to provide insight into faculty experiences across Canada (see Table 1). All participants had taught previously, but some participants had over a decade of teaching experience while others were less experienced. None of the participants had previously experienced teaching online.

Table 1. Participants by Institutional Level, Region, Years of Teaching Experience, and Professional Status

Participant* |

Institution & Region |

Years teaching |

Position / status |

Erika |

University, Maritimes |

3-5 |

Tenure-Track |

Julie |

University, Alberta |

3 |

Tenure-Track |

Gabriel |

University, Alberta |

10+ |

Tenured |

Caroline |

University, Ontario |

3 |

Tenure-Track |

Natasha |

University, Quebec |

15+ |

Sessional |

Mark |

College (Cégep), Quebec |

10+ |

Permanent Instructor |

Simon |

University, British Columbia |

15+ |

Tenured |

Claudia |

University, Quebec |

10+ |

Tenure-Track |

Jack |

University, Alberta |

10+ |

Continuing Instructor |

Monica |

University, Alberta |

10+ |

Tenure-Track |

*Note : All participants are identified by an assigned pseudonym

Data collection and analysis

In late spring 2021, we interviewed ten faculty members from different provinces and institutions and asked them to share their personal and professional experiences. Rather than following an interview script, we conducted interactive interviews, described by Carolyn Ellis (1998) as a way of exploring lived experience through everyday conversations. Unlike more traditional interview techniques that underemphasize the emotional facet of the interview relationship itself (Ezzy, 2010), interactive interviewing uses active participation of the researcher to recognize and reconstruct or redefine the relationship between researcher and participant. As Clandinin (2013) has noted, this approach to research, in which individuals’ own stories are prioritized, “begins and ends with a respect for ordinary lived experience” (p. 18). As the stories, experiences, and attitudes of the interviewer and interviewee flow into and through each other, the traditional boundaries and distances between the two participants are blurred or even erased (Fontana, 2002). We chose this style of dialogue deliberately, to reflect our aims for this research and acknowledge that the phenomenon we were investigating has affected us, Erin and Maggie, personally and professionally, as well. Aware that such conversations had the potential to become emotional and even traumatic, we included a list of mental health support options in the consent forms, which participants signed before the first interview took place.

For each interview, one of us met with a participant, usually via Zoom, for approximately an hour; we conducted the interviews separately to maintain a one-on-one structure. We began each conversation with a resumé of our project, and then allowed our participant to talk freely about any aspect of their personal experience encountered. We asked them to reflect on the “swerve” of spring 2020, the “shift” of fall 2020, and the “road forward” in 2021, and to elaborate on any aspect that they wished to expand upon. We recorded each interview, then compiled notes from the interviews, creating what Clandinin and Connelly call “interim texts” (2000, p. 133). Our data analysis process followed Braun and Clarke’s (2013) thematic analysis steps of: 1) familiarizing oneself with the data, 2) generating initial codes, 3) finding overall themes, 4) reviewing themes, 5) naming themes, and 6) producing the final report. We shared the interviews and our interim texts with each other to determine narrative analytic codes (Clandinin & Connelly 2000, p. 131), codes which then informed subsequent ‘rereadings’ of the texts. Through several rereadings of interim texts and interviews, we generated the narrative threads that emerged through the interwoven storylines of our participants. Our coding process was recursive in the sense that each time we would re-read the data or ‘interim texts’, we refined and readjusted or renamed the codes, or narrative threads, to better fit emerging insights. The next step was generating the narrative themes themselves. The naming of themes was similarly a recursive process, requiring multiple discussions as we categorized, reviewed, and re-categorized the interim texts, or codes, into cohesive themes. We used thematic analysis as a complement to our narrative inquiry because its inherent flexibility supports research questions and data that might otherwise be difficult to manipulate (Lainson et al., 2019).

Ultimately, while each educator’s experience was unique, we found common thematic patterns emerging, which we have explored below in two broad categories that cover the challenges as well as the silver linings of living and teaching through a pandemic.

Challenges and Roadblocks : Unsustainable Crisis Mode

For the participants in our study, the road through pandemic online teaching was filled with challenges, stumbles, and roadblocks: experiences that aligned with Porges’ (2107) framing of trauma. Porges defines trauma as …. The educators’ challenges took many forms as faculty were pressed to master a new teaching environment while navigating the logistical and emotional complexities brought about by a global pandemic. While all interviewees impressed us with their resilience and willingness to adapt their teaching under exceptional circumstances, the stumbles and roadblocks had unanticipated consequences, from feeling concerned about their career trajectories to navigating feelings of hopelessness due to extreme stress. Below, we summarize these challenges, presenting them within the themes of 1) Trauma and burnout : ‘fight, flight and freeze’; 2) Secondary trauma : responding to students; and 3) Difficulty in creating communities of practice for students.

Trauma and Burnout : Fight, Flight, and Freeze

Some of the most common challenges described by participants directly corresponded to Porges’ (2017) categories of movement responses: ‘fight’, as in anger and frustration, or ‘flight’ in the relentless uncertainty of the pandemic.

Trauma as ‘Fight’ Response

For some participants, the frustration they felt about their imposed swerve to online teaching created feelings of anger. This is best exemplified by Marc, a college teacher in Quebec, who expressed frustration with the perceived lack of governmental support. Marc felt he was “dealing with an employer that [didn’t] care…an employer that hates [teachers]. I have zero faith in this government.” While Marc acknowledged that his reaction to the perceived lack of governmental support was not emotionally healthy, he described it as beyond his control, stating “I don’t want to be angry. I don’t wake up in the morning thinking ‘I can’t wait to be angry.’” Marc reflected that he frequently found himself feeling anger and frustration about social media posts, and that his girlfriend had expressed concern about his mental health. Overall, Marc’s comments reflect his anger over a situation beyond his control, which can be categorized as a ‘fight’ response to the trauma experienced during the pandemic.

Trauma as ‘Flight’ response

The emotional exhaustion brought on by the constantly shifting conditions was well encapsulated in the following reflections from Claudia, a tenure-track professor at a large, urban university in Quebec, who described the situation as in “unsustainable crisis mode :”

I love teaching, I have loved teaching - I’m drawn to it more than the research - but this year I feel like I’m doing an OK job at teaching, but I’m just not putting everything into it. I could be reading more, I could be more creative, I could be doing more, and I’m just not. It was my husband who said “well, it’s obvious, you’re burnt out.” You don’t have anything left. You feel like you’ve been running and running and running, and finally you can just sit and do your thing, and then it’s like someone has pulled the rug out from under you and it’s like this cartoonish kind of running even faster.

Relatedly, some participants commented on how a climate a uncertainty, due to constantly shifting information provided by the government and a lack of coordination between institutions and government, caused a great amount of stress and anxiety. For example, Natasha, a sessional instructor and high school teacher, said: “I didn't like the uncertainty. Constant uncertainty… because people are asking you, what do you think is going to happen? And I have no idea. Because it changes from day to day or week to week, or the inconsistency between institutions and government.”

A number of our participants also discussed feeling anxious and even fearful of the virus itself. Erika, a tenure-track professor in the Maritimes described this feeling of anxiety at the beginning of March 2020 when teaching in-person in a class of 100 students. She found herself thinking, “I gotta get outta here… this is just going to be a cesspool!” This sense of anxiety about being exposed to the virus in the classroom was echoed by Jack, an instructor at an Albertan university, who joked that he was starting to hear the Police song “Don’t stand so close to me” in his head. Although Jack was able to find some humour in this situation, experiencing underlying fear and anxiety for months on end corresponds to Porges’ (2017) categorization of trauma as a flight response.

Trauma as ‘Freeze’ Response

The relentless uncertainty engendered by the pandemic led to extreme reactions of emotional exhaustion or burnout among a number of our participants, responses which aligned with Porges’ (2017) ‘freeze’ response to trauma. Freezing is characterized by feelings of ‘helplessness,’ ‘hopelessness,’ and feeling ‘trapped’ (p. ??). Such freezing was particularly acute for female tenure-track participants, who experienced extreme anxiety regarding their career progress, as explored further below. Marc’s comments also clearly articulated hopelessness and despair : “The light at the end of the tunnel just kept getting further away. Everything felt pointless. Survival mode is ok if it’s a month or two. A year later, why is this a marathon?”

Anxiety over Career

Multiple participants reported feeling anxious about their career trajectory, a response that corresponds to Porges’ ‘flight’ category of trauma. Notably, this career-related worry and stress most strongly affected female tenure-track participants with young children (Caroline, Erika, Julie), a gendered outcome of the pandemic that has only begun to be documented (Davis, 2021; 2022). For Caroline, a single mother of a four-year-old, the lack of family support in the Ontario city where she worked meant that up until the pandemic began, she had employed an au-pair to help with childcare. However, early in the pandemic the au-pair returned to her home country, leaving Caroline on her own, on her own with a full-time tenure-track position, courses to teach online, and a four-year-old to care for all day. She was compelled to work from 1 a.m. to 4 a.m. to develop and organize her courses. Her days were filled with childcare and teaching. She felt that her research was “basically destroyed,” causing her an extreme amount of stress. Erika, whose partner worked outside the home, had a similarly stressful day-to-day experience, noting that: “I kept thinking we’d hear from the administration about tenure and expectations, but nothing, and I realized, they just expect us to keep going…you’re supposed to be doing everything you were doing before, even though you have two kids at home, and can’t go into work, and so on…like are you for real?” Erika’s comments reflected a shared immense challenge, noting that “you can’t put a one-year-old down in front of the TV and go grade papers.”

Julie also faced anxiety over her career trajectory. She and her partner had two children, aged two and six at the beginning of the pandemic. Julie reported that the two-year old required constant supervision and the six-year-old was unable to manage his online schooling without help. She worried, “What happens in a year without publishing?” She said that this feeling of anxiety was heightened because her institution was not forthcoming with a definitive policy. Like Caroline, Julie felt compelled to focus primarily on her teaching duties. When she asked her department Chair if she was correct in understanding that the university was encouraging this approach, she was told that “yes [but] you have to read between the lines a bit.” In the absence of formal recognition or a policy, Julie encountered an exceptional amount of anxiety over her career progress as a tenure-track professor. That three tenure-track female parent participants experienced the same deep-seated anxiety over career progression is surely no coincidence; this finding aligns with recent scholarship urging changes to the tenure system for women and racialized faculty in order to minimize the pandemic’s harmful impacts on careers (Davis, 2022).

Secondary Trauma : Responding to and Supporting Students

Faculty members teaching online struggled to respond to and support their students who were going through their own experiences of trauma brought on by the pandemic. This created a secondary kind of trauma for study participants. For example, Natasha said she worked hard to be accessible to her students because “[t]hey were on an emotional roller coaster…they were worried about everything. They needed to talk to somebody, and I was the person that they spoke to.” And while the challenge of supporting students effectively was mentioned by participants at the beginning of the pandemic, many felt that this became more challenging as time went on. By the winter of 2021, faculty indicated that students seemed tired and disengaged, exhibiting clear signs of burnout, making it difficult to support them. Both students and instructors were “checked out”, struggling to maintain their energy and motivation as students struggled with burnout and mental health issues. Simon aptly described the scenario as a “second rate experience for everyone.”

Although Jack was able to find some humour in teaching online, he noted that “I was getting better, but the students were getting worse!” Like many participants, he noted that compared to summer 2020, by fall 2020 most students were keeping their cameras off and by the end of winter 2021 session, all cameras were off. This affected engagement significantly, creating a feeling that Jack described as: “You're teaching, but nobody is there.” Natasha recounted a similar effect when referring to the students in her evening university classes, noting that “some of them were working in person, some were online all day - you could just see the glazed looks on their faces from being on Zoom morning till night.” At times, experiences of secondary student trauma were extreme. Julie described having a student “Zoom-in” from the hospital where they were staying because of a suicide attempt.

A number of participants reflected on the challenges they encountered in trying to balance academic rigor with being compassionate and flexible. For example, Gabriel felt the push towards compassionate pedagogy was in conflict with institutional standards and expectations, causing confusion and stress. Claudia also described this tension, noting that “Some [of her colleagues] in the department are so focussed on standards - ‘students can’t get away with this just because it’s COVID.’ There’s no compassion.” Ultimately, despite uncertainty over institutional expectations, all faculty participants indicated that they worked hard to prioritize a compassionate approach with students.

Difficulties Building a Classroom Community of Practice for Students

As suggested by the cameras-off phenomenon described above, one important challenge for faculty teaching during the pandemic was the difficulty in building a classroom community online. Among the biggest stumbling blocks in using video conferencing software for teaching was the inability to gain informal feedback from students’ faces and body language that is standard in a face-to-face environment. As Claudia explained, “Online it’s so hard to see that the group is struggling with a concept, so we gloss over what would have been a deep dive in person. It’s easy to recalibrate when you’re in the classroom - it’s just so much harder online. The feedback loop is just so broken.” Her difficulties creating community in the online environment were shared by others, such as Caroline, who commented: “you can never do remotely what you can do in the classroom." It’s worth noting that Caroline was in many ways quite successful with developing and delivering her courses online, and received excellent feedback. However, she was still adamant that online teaching and learning is “just not the same.” She went on to explain how much she missed teaching in person, noting that “some of the best classes I’ve ever taught have been the ones where we go off book, and get into understanding those fundamental concepts.” Simon’s comments echoed Claudia and Caroline’s : “For me there is honestly nothing like talking face-to-face, to have a real conversation, for ideas to be shared. I believe that students are more inclined to open up when we are face-to-face.” He concluded that: “Honestly, the sooner it's over the better.” The inability or difficulty with creating an “organic” classroom community online (Donaldson, 2020, p. 247) led to frustration, creating a situation in which everyone—students and educators alike—struggled to establish meaningful connections.

Our participants’ stories about the challenges and roadblocks they encountered since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic hit home for us, as many of them shared struggles that we had experienced ourselves. Their descriptions of feeling overwhelmed with exhaustion and burnout from overlapping personal and professional demands, the underlying anxiety of shifting expectations, and their difficulties responding to students’ experiences of trauma and burnout were at times difficult to hear, underscoring the immensity of the toll that this pandemic had on so many. However, as discouraging as some of their stories were, we were heartened by how many participants found some positives amidst this extraordinarily challenging time.

Revelations, Epiphanies, and Silver Linings : Making the Best of a Bad Situation

While our participants struggled with pandemic teaching, all of them identified positive outcomes. Some silver linings were small glimmers of optimism in an overwhelmingly pessimistic time, such as when people found distraction from challenging obligations. Some relished the motivation to create a work-from-home space or took some small joy in avoiding stressful commutes. More pertinent to our exploration were the recurring themes of taking time to reflect on, and deepen, pedagogical practice, resetting professional and personal priorities, and finding solace and solidarity in communities of practice.

Reset, Rest & Nest

Several participants shared that the sudden shift to online teaching, and to working from home, felt initially like a chance to reset. Given that many believed that they would be returning to campus within weeks, having some time at home was “like taking a vacation from ‘normal life’,” as Marc put it.

Marc was one participant who embraced the swerve at first, not least because it was a distraction. Just prior to the shutdown, Marc, who was dealing with the emotional ramifications of the death of his father in 2019, experienced the death of a close friend. He said that the pandemic kept him distracted, and that he “needed to be occupied” to avoid his grief. Natasha, too, was facing challenges long before the pandemic. Both her mother and brother are in long-term care, and in early 2020, her mother was in and out of hospital. Natasha was exhausted. On top of caring for her mother and brother, she was teaching high school full time, lecturing part time at her university, and working on her doctorate. The pandemic forced her to take the time off that her doctor had been advising; the long-term care facilities could not allow visitors, and the schools were closed, so she had no choice but to slow down. As she said, “the pandemic paled in comparison to some of the things [she] had been living through.”

Working from Home Means Making Home Workable

As the pandemic stretched out and it became clear that most faculty would be continuing to teach remotely for the fall and winter terms, some took the opportunity to make their work-from-home environments cozier. Once the challenges of finding space and getting tech savvy were addressed, there was time and motivation to paint and decorate. Although Erika felt that working from home was challenging because of her young children demanding attention, she was happy to have the opportunity—even if imposed under stressful circumstances—to paint and decorate the guest room, which then served as her office from home during the pandemic.

For some participants, the swerve alleviated stress related to parenting, commuting, and scheduling. Jack’s schedule in early 2020 was particularly difficult; he had been teaching three days each week and expected to be on campus for office hours the other two days. He was starting to feel exhausted, so when the campus shut down and everything moved online, he felt relieved. Caroline discovered that online teaching and learning could work well for people who are parents; in fact, she became one of many who are now advocating for departments to continue holding meetings online. She also pointed out that it was much easier to get guest speakers to address classes and other groups online. Claudia, too, felt that “some bonds have been tightened,” such as in her writing group, which moved online and continued to meet weekly throughout the pandemic.

Furthering our Practice

Several respondents talked about how the shift to teaching remotely forced them to follow through on formerly nebulous plans to update their syllabi and get to know digital tools. As well, institutions went into overdrive, providing workshops and tutorials beyond the basics, to support their faculty in myriad ways. Despite the challenges of planning for online courses and teaching remotely, many participants felt that the pedagogical challenge made them take stock, enact changes, and develop their practice far more than they would have without the imposed measures.

Discovering Digital Tools

Naturally, the swerve and, in particular, the shift in the autumn of 2020 to online teaching and learning, required teachers to adopt new technology and get to know existing technology in more depth. For some, this emphasis on digital pedagogical tools was welcome, and they—indeed we—embraced the admittedly steep learning curve as we prepared our online courses. Natasha put it this way : “This may sound crazy because we’re living through a pandemic, but I wanted to try, and to play with technology, and see what are the options I can use.”

Others felt that excitement wane as the pandemic wore on and began to feel that the light at the end of the tunnel was receding. Claudia, who found that “at first, it was exciting to try new things,” put a lot of work into moving her courses online. However, she asserted that she is happier in the classroom, even after a year of teaching successfully online. Like other respondents, Claudia was able to identify take-aways from online teaching that will follow her back into the in-person classroom, such as discussion boards and group work. These tools, she said, allowed her to hear from students that would not have spoken up in person, and created a sense of community among students.

Reflecting on Practice and Priorities

For Jack, the pandemic created the need to reimagine his syllabus and streamline his course material. He said that this process was one he had been considering before the pandemic, but the swerve finally gave him the push to move forward with the changes. Reflecting back, Jack says that his teaching has changed for the better, and that seeing himself teach on screen every day made him acutely aware of his tone of voice and body language, and how the physicality and performance of teaching matters.

Jack and Monica concurred that pandemic teaching showed how ‘less is more.’ Both felt that streamlined content and more space for discussion and exploration made their courses stronger. Other participants felt that teaching remotely showed them how to identify what was really important in terms of content and assessment. As Monica observed, her students “didn’t come out less prepared” than her previous cohorts because “students can only absorb so much.”

The longer-term change, for many, was a shift in priorities to more humane expectations. More than half of our participants are tenure track faculty, many of whom made it clear that while they initially felt stymied by the unexpected setback on their tenure path, ultimately the pandemic helped them rethink their priorities. One of these participants was Erika, who said that institutions will have to make tenure decisions based on work done in context :

I know I have been less productive, but I have to be realistic. In a way, the pandemic has taken the edge off. You just can’t be super competitive. If what I’m doing isn’t enough to get tenure, then I’ll get another job. I’m less anxious about things I used to worry about, because I think I see the bigger picture.

By “bigger picture,” she was alluding to work-life balance. Erika was one of several participants parenting young children while building a tenure portfolio; both she and Claudia felt that the circumstances of the pandemic ultimately took some pressure off the tenure race. Caroline, like Claudia and Erika, initially felt enormous stress because she fell behind in her research and publishing, but eventually, she recognized that the situation was beyond her control. Once she had that revelation, she felt much more relaxed. However, like the others, she remains concerned about the long-term impact on her career trajectory.

Communities of Practice

Going into the shift to online teaching in the fall 2020 semester, many of us were preoccupied with how to create a sense of community among students who were nothing more than several black boxes on a screen. If necessity is the mother of invention, then remote teaching is the parent of creative pedagogy. Faculty rose to the challenge of creating a classroom community, deploying several strategies from mastering the art of the breakout room to monitoring ongoing discussion forums.

When we asked our participants what surprised them about teaching online, the overwhelming response was the resilience, optimism, and engagement of their students. Many said that the student attitude was better than that of some colleagues, and that students were not only participating in classroom activities but seeking out one-on-one meetings with their instructors like never before –there was certainly something to be said for the virtual office hour.

Several of our participants also talked about feedback from students who loved the online forums and semester-long collaborative groups, because they found a sense of connection. Even though Claudia insisted that “conversations, in the classroom and in the hallway, need to be a thing again,” she intends to maintain online discussion forums in her courses, as they proved so helpful to her students during the pandemic.

Finding our Communities as Teachers

After the initial shock of the pandemic and the sudden swerve to online emergency teaching, many participants said they were buoyed by a genuine sense of community and communal effort toward a common goal. For Marc, “[it was] crazy, [it was] wild, but we’ll get over it, and we’ll laugh about it.” What he described as an “interesting challenge” was something on a large, collective scale. Marc likened it to the experience of going to war for the weekend, but from a safe position. People were not yet experiencing pandemic fatigue, so there was a lot of community work. Participating in this work felt really uplifting. Marc and his partner bought and delivered groceries for his in-laws, for local families in need, and for a friend who was a single parent and front-line worker. Marc said that “in some ways, even though we were at home, there was a sense of connection to other human beings that [he] hadn’t felt in a long while.”

Together apart

Social media became a site of community of practice during the pandemic. Nodes of this organic community of practice, in virtual spaces such as Facebook groups and Twitter hashtags, sprang up across the country (McDonnell, 2022). All of our participants talked about their experiences with these online spaces as practice-enhancing, making the situation more bearable. Most stated that they intended to maintain their connections with online communities of practice, both with peers and with students. Claudia, for instance, observed that “people are used to having little online communities now. This year has been great for some students.” Gabriel talked about how much he benefited from conversations with a colleague who was “many steps ahead” in planning for online teaching, and how much he appreciated the community he discovered through his institution’s faculty training and resources. Julie told us that when she was struggling, she reached out to her department to ask if they could establish a Tuesday lunch session on Zoom. That departmental virtual lunch is something that they continue to do in order to stay in touch with each other. She says it helps.

All of these personal responses correspond with Porges’ (2017) notion of the social engagement system; as Wright (n.d.) put it, “when we enhance our connection with other people, we trigger neural circuits in our bodies that calm the heart, relax the gut, and turn off the fear response.” In our non-pandemic work life, it is relatively easy to connect with each other (Wenger 2009) so we take these connections for granted. As Donaldson (2020) has suggested, creating virtual communities of practice may take more explicit intention, but individuals benefit from membership in a community of practice, and feel “less alone” (McDonnell, 2022).

In fact, some of our participants found that the more conscious effort of participating in a digital community of practice enhanced the experience and deepened their sense of connection. Erika, who is a member of an academic writing group, said that the group moved online, and met every week, but often just talked instead of conducting a formalized writing session. She explained that the writing group was one of “those great relationships that are going to keep going forever. Some bonds have been tightened.” Even bureaucratic impediments have been eased through online community action. Claudia is part of a group of women from her institution who have successfully petitioned the administration to create a task force of caregivers out of the current faculty or staff.

Final Thoughts

“It will be interesting how this changes the world. Or doesn’t. I’m rather worried that it won’t.” ~Erika

Not long ago, writing an article about teaching during a global pandemic was nowhere on our radar – or anyone else’s. The full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on those tasked with teaching in Canadian institutions of higher education has yet to be fully documented. We were, at the time of writing, still in the midst of this unprecedented global crisis. As members of the higher education community, we witnessed and experienced first-hand many of the challenges and epiphanies brought about by the sudden swerve and shift to remote teaching. As academics interested in the transformative power of stories and storytelling, we wanted to provide an opportunity for our peers to share their stories of navigating the roadblocks that remote teaching presented. From experiencing emotional and mental burnout themselves, to struggling to support students who were often in crisis, faculty educators encountered a constantly shifting landscape that impacted their professional and personal lives. Of course, the impact of the pandemic was felt by all our colleagues far beyond any one classroom. After our interviews, we began to refer to “The Russian Doll Syndrome” : each person’s professional experience during this pandemic was just one layer, nested within their experience at home, which was nested inside concerns for friends and family, and so on. No one lives through a pandemic with only the pandemic to worry about.

Ultimately, we are inspired by our participants’ resilience and encouraged by their ability to find the silver linings during this pandemic. As these interviews demonstrated, and as validated by our personal experience, perhaps the biggest boon from this unprecedented collective experience was the emergence of virtual communities. These communities of practice have been essential to many teachers’ professional and personal well-being throughout the pandemic. Since March 2020, educators across the country and around the world have shared resources, given each other tech support, engaged in thoughtful discussions about many aspects of our pedagogy, and been each other’s sounding boards. This organic collaboration has demonstrated beyond doubt the effectiveness of communities of practice, and the essential nature of collaboration as we swerve and shift with the tides of change.