the MJe forum / le forum de la rsém

Who am I, Really? Reflections on Developing Professional Identity as a Cégep Teacher

MAGGIE MCDONNELL Concordia University

This year, I am celebrating my 20th anniversary of teaching in higher education. Most of those years have been spent teaching at the Cégep level [collège d’enseignement général et professionnel]. Teaching at the Cégep level is an attractive prospect for many academics; the qualifications are not quite as stringent as university teaching, and there is no research expectation. Like our university colleagues, however, Cégep teachers often find themselves walking through the door of our first classroom only to be hit by panic — do we know how to be Cégep teachers?

How we spend our days

Writer Annie Dillard (2013) reminds us that “how we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives” (p. 27). How we spend our days, of course, is working — recent research shows that the average person spends a third of their life, close to 90,000 hours, working (Gettysburg College, 2021). What we do in our professional capacity, then, inevitably influences who we are personally. Philosopher Al Gini (1998) says “it is in work that we become persons. Work is that which forms us, gives us a focus, gives us a vehicle for personal expression and offers us a means for personal definition” (p. 708). As teachers, we do not work in a vacuum, and our identity as teacher is constructed and reconstructed in a social context. Interactions with students, with colleagues, with administrators, influence our professional identity and, in turn, our practice.

Faculty in higher education are often discussed collectively, as if individuals within the group share a predetermined and universal set of characteristics. Yet, even from the student perspective, it is clear that no two teachers are alike. Beyond practical differences in our pedagogical approaches we are, of course, individual human beings, with personal identities that inform our professional identities.

Identity is a term that is perpetually being probed and explored, and our understanding of the term is influenced by our discipline and context. Most explorations of identity agree, at least, that identity is not fixed, but develops and evolves over time (Trautwein, 2018). Our identity as academics and teachers, as is true in other professions, is influenced by internal and external factors, past and present experiences. The teacher we are today is not the teacher we were yesterday, nor the teacher we will be tomorrow, or next year. Trautwein (2018) says, in short, “the process of identity development in teaching can be described as a complex, career-long process” (p. 997).

Each of us embodies several roles. We might think of these roles as identities, in the plural (Fearon, 1999); howsoever we choose to label them, what is important is that we recognize them, and appreciate how each one influences the others. My identities as student, citizen, relative, and teacher are not necessarily the same — or perhaps more accurately are necessarily not the same (Fearon, 1999). Other aspects that are perhaps more indelibly part of our selves, such as behaviours, beliefs, opinions, values, skills, experience, and family history, are assumed to be carried with us, regardless of context (Fearon, 1999).

Ultimately, as one might imagine, it is hard to pin down any one fixed definition of professional identity; however, Avidov-Ungar and Forkosh-Baruch (2018) identified four facets:

professional identity as an ongoing process of interpretation of experiences and responses to the questions “Who am I now?” and “What would I like to be in the future?”; professional identity as reference to the individual and the context of his or her actions; professional identity as a sum of sub-identities in harmony; and professional identity as requiring involvement and activity of the professional. (p. 185)

To better understand what it means to be a Cégep teacher, then, we might ask ourselves four questions, based on those characteristics:

Who am I now, and who would I like to become?

Who am I in this role?

Who am I in this context?

Who am I in this community?

I take up each in turn — and, in this Forum piece, invite others to do the same, in whatever manner seems most appropriate.

Who am I now, and who would I like to be?

Teacher is such a ubiquitous term that some may feel that there is no need to define it — a teacher is one who teaches. Therefore, a Cégep teacher is one who teaches at Cégep. What could be simpler?

Many metaphors have been used to illustrate what we mean by teacher: medical metaphors (teachers are doctors, and the students’ illness is ignorance), military metaphors (teaching is about instilling discipline and conformity), agricultural metaphors (teachers plant seeds), and even spiritual and religious metaphors (school as sanctuary, and teacher as mystic / priest) (Badley & Hollabaugh, 2012). Weimer (2016) described teaching as midwifery, and teachers as “present at the birth of learning” (para. 3). Cégep teacher educator Denise Barbeau (as cited in Doucet, 2016) has compared teaching to directing theatrical productions or being a gardener, metaphors clearly rooted in Barbeau’s notion that the task of teaching “is not to showcase our own knowledge, but to guide students in developing theirs” (in Doucet, 2016, p. 5). She elaborated, using the following felicitous phrase: “a teacher’s role is to foster harmonious contact” between the learning task and student (in Doucet, 2016, p. 5).

The fact that so many different metaphors exist to describe what it means to be a teacher, or what it means to teach, suggests that the concept of what a teacher is, is not that simple after all. If nothing else, the constantly evolving theories of learning and knowledge would imply a parallel shift in how we understand what it means to teach; we have progressed well beyond the Skinner model of behaviourism in learning, and teacher as source of punishment and reward. Badley and Hollabaugh (2012) identified three ‘clusters’ of teaching metaphors that seem to reflect our evolution: transmission, facilitation, and catalyst. Metaphors from the transmission category emphasize teaching as the act of moving information from the source to a destination, often perceived as an empty vessel to be filled with the teacher’s knowledge. Much of our common expressions in education are in fact rooted in this perception. Consider, for examples, idiomatic expressions such as getting ideas across or getting through to students. Badley and Hollabaugh (2012) suggest: “when a teacher attempts to become the sole transmitter and interpreter of knowledge (the principle source and cause of learning) within a classroom, meaningful learning is easily undermined” (p. 56).

The notion of the teacher as facilitator is arguably a more commonly used metaphor in contemporary, more student-centered, pedagogy. While a facilitator may seem like a friendlier way to think of teaching, as Badley and Hollabaugh (2012) point out, a teacher must still have knowledge to transmit. Furthermore, as the coaching metaphor suggests, this model of teaching, while maintaining the idea of facilitation, highlights the importance of motivation and inspiration: “Good coaches are able to inspire those they coach to perform at their highest level, whether in training, in competition, or in life experiences” (Badley & Hollabaugh 2012, p. 59).

The teacher as catalyst is one who generates dissonance to inspire learning, by playing devil’s advocate, engaging in Socratic dialogue, or simply stirring the pot. Dissonance becomes the irritating grain of sand that ultimately transforms into a pearl. Proponents of the teacher as catalyst claim that students are more engaged in their learning; however, Badley and Hollabaugh (2012) caution that while lively and rigorous debate might engage students, curricular objectives cannot be neglected. Engaging in this approach to teaching requires “exceptional classroom leadership and discussion-leading skills” (Badley & Hollabaugh 2012, p. 63), sensitivity to student discomfort, recognition of boundaries, establishment of safe learning spaces, and recognition of “the ceiling of students’ capacity for dissonance” (Badley & Hollabaugh, 2012, p. 64), so that students are not so stressed that they lose sight of the purpose of the task.

The danger with metaphors is essentialism. Just as our identity is multifaceted and ever-changing, so too is our teaching practice. It is not that we do not transmit, facilitate, or inspire, but rather we engage in all three, this along a spectrum, in response to the actual context — the subject, the level, whether the class meets at 8 a.m. or 2 p.m., even our own familiarity with the topic — all of which also manifest in particular ways in the Cégep system.

Who would I like to become?

How might we consciously develop our professional identity? As we think about our future as Cégep teachers, it is imperative to look not only at our current practice, but also at our own lived experience as students. Are there teachers in our past who we are, consciously or not, emulating? Are there discipline-specific conventions around teaching and learning that we are relying on by default?

In her extensive review of research on teachers’ professional identity, Izadinia (2013) reported that “all studies suggest that having [student teachers] reflect upon their own values, beliefs, feelings and teaching practices and experiences helps shape their professional identity” (p. 699). Becoming reflexive in one’s practice includes becoming conscious of the “continued influence of former teachers” (Lortie, 2005, p. 139), and teaching habits hitherto unconsciously embraced, and, most importantly, acting on that consciousness to change our practice. This is not to say that all of those habits are necessarily bad; in fact, as Lortie (2005) pointed out in his seminal study (first published in 1975) people “usually have little difficulty in recalling their former teachers and, particularly, in discussing those they consider ‘outstanding’” (Lortie, 2005, p. 139). Lortie’s (2005) discussions with teachers, however, revealed that even when they were aware of former teachers’ influence, they did not recall those teachers in terms of instructional strategies or assessment practices, but in terms of personal warmth and nurturing. If teachers are to become reflexive practitioners, they can start by recognizing the disconnect between the qualities they remember as “outstanding,” which Lortie discovered tend to reflect “nurturant” qualities (Lortie, 2005, p. 140) and those that they identify as important in a professional capacity — and perhaps start to also question why the notion of being nurturing is somehow alien to professional practice. The many hours spent as a student constitute what Lortie (2005) called an apprenticeship of observation (Lortie, 2005, p. 61). I spent 24 years watching other people teach, three of them as a Cégep student, before I stepped into a classroom as a teacher myself, and I only deliberately sought out training as a Cégep teacher two years after I had begun teaching. Why was that?

Who am I in this role?

When researching teacher development and identity, the research focus (perhaps naturally) tends toward new and pre-service teachers, rather than veteran teachers and their development. Flores and Day (2006) identified two milestone phases in the professional development of new teachers: “the threshold and the growing into the profession” (p. 220, italics in original). They characterized the threshold period as a confrontation between the new teachers’ ideas of what teaching was and the realities of their everyday classroom experience; teachers embarked on their new careers “from a more inductive and student-centered approach” (Flores & Day, 2006, p. 227) but were quickly derailed by the transition shock. The crisis of this transition shock tended, in these teachers, to invoke a shift toward “more ‘traditional’ and teacher-centered [approach] (even if their beliefs pointed to the opposite direction), owing to problems associated with classroom management and student control” (Flores & Day, 2006, p. 227). As new teachers, they tended to “use the history of their own schooling and [emulate] specific teacher role models” (Enyedy et al., 2005, p. 70). In other words, when faced with challenges in the classroom, teachers tended to fall back on their own experience as students and engage in “strategic compliance” (Flores & Day, 2006, p. 225).

Flores and Day (2006) noted, as did Borg (2004) and Lortie (2005), that this strategic compliance is recognized by new teachers; most have “personal reservations” (Flores & Day, 2006, p. 225) about using conventional methods. Although such methods may temporarily solve the problems associated with transition shock, as teachers grow into the profession, they “tend to focus their attention on the improvement of skills, methods and competencies” (Flores & Day, 2006, p. 220). Gradually, tentatively, in “an ongoing and dynamic process which entails the making sense and (re)interpretation of one’s own values and experiences,” (Flores & Day, 2006, p. 220) these teachers create their own professional identity.

In Cégep teaching, the transition shock for teachers has little to do with entering the profession from particularly progressive pedagogical theories, since most have not studied those theories prior to their entry into the profession. Relying on more traditional teaching practices is perhaps even more prevalent in higher education, simply because so many of us have not been exposed to the evolution of pedagogy through formal teacher training. The real shock for us comes from the realization that our students were not simply younger versions of ourselves. We are faced with students who struggle with concepts that came easily for us, students who do not love our topic — or even school — the way we do, students whose goals are radically different from what ours were. How we cope with that realization and, I hope, how we learn to appreciate those differences and find pedagogical approaches that speak to our students, is a milestone in our developmental journey.

So, what is Cégep?

In practical terms, Cégep is what comes after high school for students in Quebec, and leads either to university studies or directly to the job market. While there are two-year colleges outside of Quebec, the concept — and politics — of Cégep, the collège d’enseignement général et professionnel, may be harder to grasp for those who have not encountered Cégep before. One might place it in the same category as junior college, or 6th form, or Grade 13, but, ultimately, Cégep really is not quite like anything else.

Perhaps the most distinct feature of the education system in Quebec is that postsecondary education begins earlier than in the rest of the continent. Quebec students complete high school studies in Secondary V, otherwise known as Grade 11, which means that they typically graduate at 16 or 17 years old. Students are not required to continue their studies beyond high school, and graduation from high school does not allow direct, immediate entry to university-level studies. Most Quebec graduates choose to continue at one of the province’s 48 Cégeps.1 Students can choose to do a two-year pre-university program, such as Social Science, Science, Commerce, or Liberal Arts, or they can opt for a three-year technical program2, such as Animal Health, Nursing, Aerotech, or Professional Theatre. Certification from the three-year programs denotes professional competence; for instance, students graduating from the Nursing program are qualified to work in Quebec as nurses, without mandatory university certification.

A brief history of the Cégep system

The Cégep system is one of the many outcomes of the political transformation of mid-twentieth century Quebec. In the early 1960s, Quebec was in a period of social upheaval, conventionally referred to as the ‘Quiet Revolution’ (la révolution tranquille), after la grande noirceure (the ‘Dark Ages’). The noirceure was an era marked by almost two decades of conservative governance under Maurice Duplessis’ Union Nationale, with heavy influence from the powerful Catholic Church. Based primarily on the work of the Parent Commission of 1963, reform in higher education in the province was intended to address the clear disadvantages of the noirceure hindering Francophone students, as compared with their Anglophone counterparts (Burgess, 1971; Magnuson, 1986). Burgess (1971) noted, for instance, that despite the significantly larger Francophone student population, pre-reform post-secondary education offered the same number of spaces to both English-speaking and French-speaking students. In 1960, approximately 3% of university-aged Francophones were in university, as compared with 11% of Anglophones; in both populations, most students were male, and several programs excluded female applicants altogether (Pigeon, n.d.). Adding to this disparity was the post-war Baby Boom, which created an even larger population of young Francophone adults, competing for a scant 7,500 spaces allocated among the three French universities: Université Laval, Université de Montréal, and Université de Sherbrooke (Pigeon, n.d.). Finally, regional disparity meant that the rural areas (which were predominantly Francophone) were underserved, while Montreal (predominantly Anglophone) was home to the lion’s share of post-secondary educational institutions, both French and English (Magnuson, 1986).

The Parent Report

The five-volume Rapport de la Commission royale d'enquête sur l'enseignement dans la province de Québec, published between the spring of 1965 and summer of 1966, is more commonly referred to in both English and French as ‘the Parent Report / le rapport Parent.’ Under the leadership of Msgr. Alfonse-Marie Parent, a Catholic priest and educator, the commission brought together nine leaders in education from the English and French communities, to study the crisis in education in the province. The Parent Report (Pigeon, n.d.) proposed a major reform, with 500 recommendations, and five main objectives:

To provide greater access to higher education for the larger Francophone population;

To provide technical and vocational programs of study, in both languages;

To instill some form of coherence between the hitherto separate English and French systems;

To regulate both systems in order to be more credible and useful both domestically and internationally;

To integrate general education, that is, the humanities, into all programs.

The Parent Commission, widely regarded as the catalyst of a seismic shift in education in Quebec, also sparked the creation of the Ministry of Education in 1964, deliberately distancing higher education from the control of both the federal government and the Catholic Church (Durocher, 2015), further establishing post-secondary education as a right, not a luxury (Pigeon, n.d.).

The early days

As its acronym suggests, Cégep (viz., collège d’enseignement général et professionnel (college of general and professional education), from its inception, offered two streams, namely, the two-year pre-university track and the three-year technical track. According to Burgess (1971), the Cégep system was consciously designed to be unique, rather than an imitation of an already-existing institution. Cégep is exceptional in that its programs are not parallel to the first two years of university programs, but are conceived of as a transition as well as foundation. Like the British sixth form, Cégep can be a steppingstone to further post-secondary education; however, unlike the British system, each Cégep is its own institution, physically and administratively, and can offer a wider range of programs (Burgess, 1971).

Evolution towards the Program approach

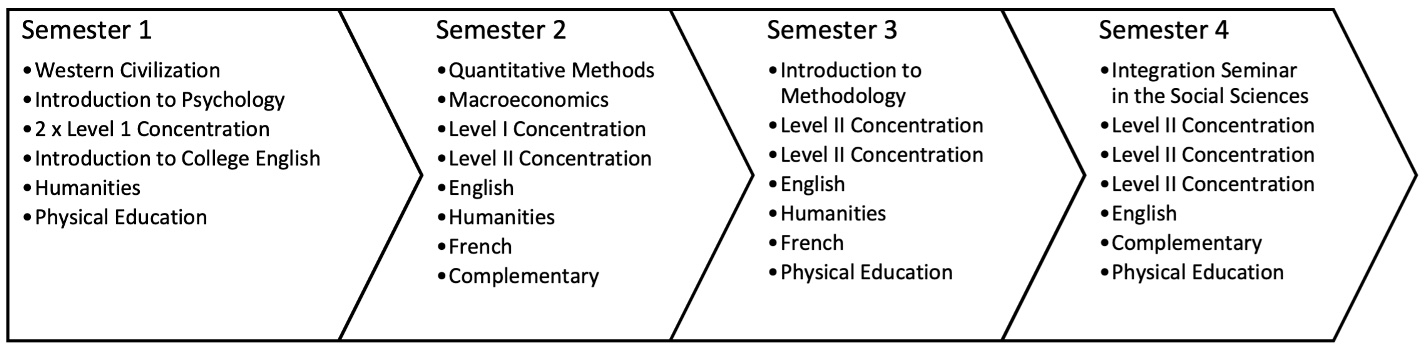

Over the past fifty-odd years, the Cégep system has undergone frequent scrutiny. The Robillard reform of 1993 was the first to result in significant changes, most notably to a competency-based program approach, which is still the model used today. Under this model, courses within a program are designed not only to meet the learning objectives of the individual course, but to work toward a holistic, program-related exit profile (see Figure 1). All programs culminate in a required comprehensive assessment (sometimes referred to as the integrative project) through which students demonstrate their competence in the program’s objectives (Dawson College, 2021).

FIGURE 1. Program grid for social science, adapted from Champlain College (2020). Level 1 and level 2 concentration courses allow students to choose from courses in Anthropology, Biology, Business, Economics, Geography, History, Sociology, Political Science and Psychology.

Who am I in this context?

Identity is constructed, and it is contextualized — and, as teachers, that context is the classroom, a space that Danielewicz (2001) said we must inhabit as if it is “the most natural place in the world” (p. 10). Importantly, Danielewicz (2001) described the classroom as a social setting, in other words, as a primary site of interaction. This implies that the classroom is a principal site of meaning-making for our students — and ourselves. This notion of classroom as natural habitat also implies that we be prepared to adapt, develop, and even defend that environment.

In higher education, the ‘apprenticeship of observation’ phenomenon is heightened by the fact that Cégep teachers are employed to teach as experts in individual disciplines — that is, English Literature, Chemistry, Respiratory Technologies — rather than based on their accreditation as teachers. Thus, our individual professional identity, and in turn our pedagogical approaches and attitudes, reflect this non-academic affiliation. In other words, we only become teachers after we have already become a nurse, a sociologist, or a chemist.

In an interview with Isabelle Fortier (2007), Cégep teacher Caroline Chateauneuf reflected on her development as a teacher:

when I first began as a CEGEP teacher, I considered myself primarily a guidance counsellor. I was eager to defend my professional identity as a guidance counsellor. I was anxious about losing this identity. … During the master’s studies program … I realized that my professional identity as a guidance counsellor was affecting my teaching practice. In fact, my teaching and evaluation styles bear a close resemblance to my image of myself as a guidance counsellor. … [T]hrough [reading] and exchanges with other teachers, I realized that my guidance counsellor identity could not be ignored but it could be moulded by my teaching position. Being a college teacher does not mean I lose my identity as a guidance counsellor. It simply means that I am unique in my way of teaching and the way I view my practice. (p. 2)

Similarly, Thornton (2011) has explored the “dual roles of artist and teacher” (p. 31). Thornton’s focus was on art teachers, but much of what he found applies to Cégep teachers as well. He wrote that “art teachers for whatever reason (there can be complex motivational factors involved) have chosen to teach” (Thornton, 2011, p. 34), but

there seem to be a variety of difficulties some experience regarding identity. There are teachers of art who feel uncomfortable because they are not making art. There are artist teachers who feel uncomfortable for not devoting themselves more to teaching. There are artist teachers who believe they can only function in both roles if they keep them separate. There are artist teachers who are concerned not to impose their own ideas as artists on their students. There are artists who work in residencies who are not sure whether to act as teachers or artists when working with students. There are artists who are determined never to teach for fear of losing their identity as artists. (Thornton, 2011, p. 35)

These struggles of artist / teacher identity can be extrapolated to the larger post-secondary teaching community, and to the idea that our sense of professional identity directly influences our practice, regardless of discipline. Enyedy et al. (2005) point out: “A missing component in the construct of [teacher] identity is practice” (p. 71). While our competence as teachers is based in our knowledge — both pedagogical and disciplinary — and our beliefs about learning and about our subject matter, these factors are “mediated by a teacher’s multiple, professional identities” (Enyedy et al, 2005, p. 69). These identities, in turn, lie “at the intersection” (Enyedy et al, 2005, p. 71) of personal history and culture, and community of practice. Izadinia (2013) echoed this when she wrote that teacher identity lies at “the intersection of personal, pedagogical, and political participation and reflection within a larger sociopolitical context” (Izadinia, 2013, p. 694).

Being a Cégep teacher

Ideally, Cégep is a valuable learning transition stage for students, and the size and distribution of the system supports the creation and delivery of a wide range of three-year programs, sustained by the larger infrastructure of each college. Programs such as Dental Hygiene (offered only at John Abbott College in English, and in only two Francophone colleges) or Aerospace Engineering, offered exclusively at Edouard-Montpetit’s School of Aeronautics, would likely not be viable as stand-alone schools, but the multidimensional and multidisciplinary nature of the Cégep system allows them to flourish. At the same time, the fundamental curriculum of most Cégep programs, with their emphasis on relatively small class sizes, means that post-secondary education can be offered in areas of the province that might not sustain a university.

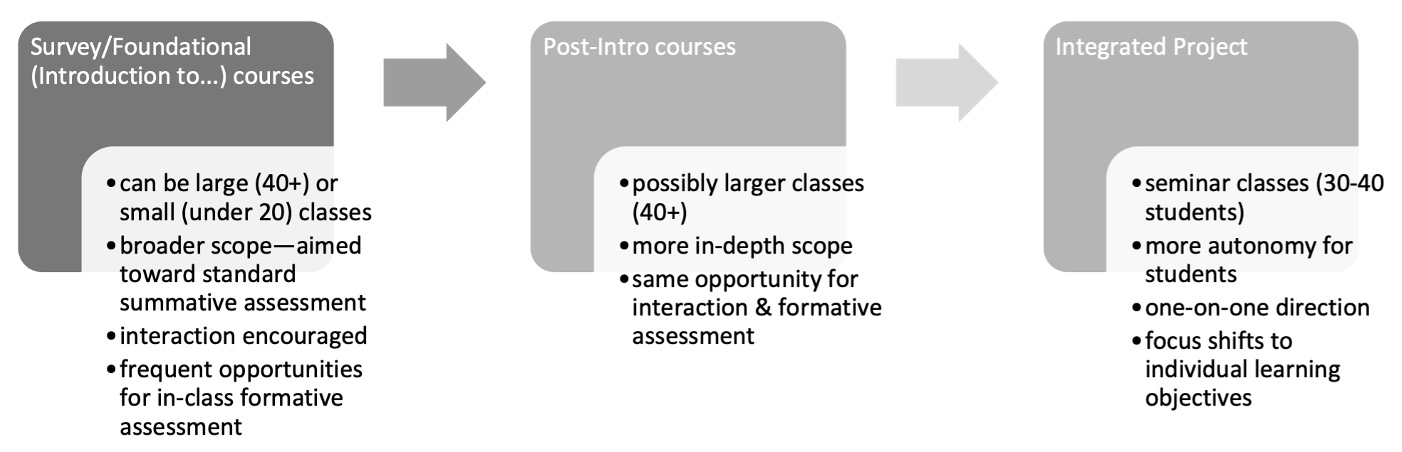

Many of us, as reflected in my research on Cégep teaching (McDonnell, 2020), are well aware of the distinct nature of Cégep, even if it is not always easy to articulate. For one thing, we have class sizes that are more amenable to interactive, collaborative learning strategies.3 Whereas university courses often take place in large lecture halls with enrolment of over 100 students, in Cégep, even first-year courses are significantly smaller — no more than 40 students, and deliberately so.

For this reason (among others), Cégep can be an attractive teaching opportunity. Further, most Cégep teaching positions (pre-university or technical) require a master’s degree or equivalent, rather than a doctorate.4 Furthermore, Cégep teachers are not required to conduct research, publish, or present their work at conferences, although many institutions support individual teachers who wish to pursue such endeavors; several institutions have affiliations with grant-funding organizations such as Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) or Entente Canada-Québec. Although informally, Cégep teachers may use the term ‘tenure’ to refer to permanent status, there is no tenure process at this level; teachers accrue seniority and achieve permanence after a certain number of consecutive full-time contracts.5 Teaching in Cégep is a largely autonomous affair. Teachers are not accountable to parents and in fact, by law, teachers cannot discuss student performance or progress with parents of students over 18.

Teaching in Cégep, for those who love teaching, can therefore be incredibly rewarding. Like any profession, it comes with its good days and bad days, its highs and lows, its annoying colleagues as well as ones who become fast friends. New teachers may find themselves languishing in a Continuing Education or part-time wasteland for some time; however, unlike the university setting, there are no adjuncts or limited-term appointments. It may take time to get to achieve job security, but once in the door, you are on your way.

Who am I in this community?

Just as the term identity is complex and layered, so too is the term community. We embody several identities, finding ourselves as members of several communities. Our several identities interact and intersect, just as these different communities overlap and exert influence on each other.

In our professional identities as Cégep teachers, we participate in some communities actively and consciously, others less so. From our very first day on campus, we have already interacted with Human Resources (HR) colleagues, our faculty dean, and a few department members. Soon after, we get to know our students — each classroom becomes its own community, with its own dynamic and momentum. Over time, we get to know our department colleagues, and likely other teachers, and sooner rather than later, we start to feel inextricably part of this place.

More subtly, we also become embedded in the culture of the college, and the larger, perhaps less tangible, idea of the Cégep system. As reflective practitioners, we need to understand the values and mission of that system, because those values, and that mission, are at the core of what we do.

Organic communities of practice

One of the most rewarding aspects of Cégep teaching is the opportunity to just sit down and talk with colleagues. Over the past twenty years, I have participated in countless conversations about teaching — in the hallways outside our classrooms, in our offices, over drinks after department meetings, even at dinner parties, much to the exasperated chagrin of our respective partners. We have talked about great books or articles to use in class, shared ideas for assessments, sought help in dealing with challenging students, argued over commas in department motions, and vented about administrative decisions.

Some new teachers are fortunate to encounter a more experienced colleague who becomes a mentor. More often, what we find instead are mentoring moments. These moments share a few characteristics: they are typically peer-to-peer dialogues (although not exclusively); they are mutually beneficial (both parties get something from the dialogue); they may arise from a crisis but are not really designed to solve a problem — rather, they allow both people to explore ideas, share experiences, and brainstorm strategies, without trying to find the one-and-only way to deal with the crisis.

So, for example, I might engage in a discussion with my colleague Jane about our deadline policies, perhaps because one of us is dealing with a situation that has made us question our current policy. I will talk about what my policy is, and Jane will tell me about hers. We will naturally talk about how our policies differ — maybe Jane refuses to accept any submissions more than three days after the deadline, whereas I accept them but provide no feedback, or deduct 5% for each day late. Perhaps I will realize that my policy now is pretty different from what it was five years ago, and we will talk about what changed and why — maybe I have stopped deducting marks for late submissions because I reflected on that practice and came to the conclusion that I wanted the grade to reflect the work done, not the time management. Maybe it is the other way around, and I have realized that I want students to learn how to manage time and workload, so my deadline policy now reflects that desire. Jane and I might talk for an hour or so, sipping tea, sharing stories of students who have tested our policy patience. In the end, maybe one or the other of us will adjust her policy; maybe neither of us will make any changes. No matter what, we both will feel more confident in our policy. In discussing, exploring, challenging, reflecting, we have come to understand better why our policy is what it is. We can better articulate the how and why of our policy.

If how we spend our days determines how we spend our lives, then who we spend those days with also determines how we feel about our lives. Good colleges will support teachers with resources and training, but good colleagues will also support each other — and this, I found in my time there, was one of the greatest defining ‘moments’ not only in shaping me as a Cégep teacher, but in understanding what that meant to me.

Reflections

The teacher we are today is not the teacher we were yesterday, nor the teacher we will be tomorrow, or next year. If professional identity is indeed a “sum of sub-identities in harmony” (Avidov-Ungar & Forkosh-Baruch, 2018, p. 185), then a Cégep teacher is a complex creature indeed. Like any other professional, we are at our best if we are willing to be reflective, asking ourselves not only who am I now? but also, who would I like to be? We must understand ourselves in the context of Cégep teaching, and how that context determines our role. We must also understand ourselves as members of communities, both large and small, formal and organic. The large-scale, historic mission of the system resonates, perhaps, but we are most authentically ourselves, and continue our development professionally and personally, when we find ourselves within our local, organic community of Cégep practice.

Notes

In 2009, Quebec had the highest rate of post-secondary graduates, with 71.7% of Quebecers between 25 and 29 with a post-secondary diploma. The national average in the same year was 65.2% (Statistics Canada, as cited in Perron, 2011). Perron (2011) credits the Cégep system, introduced in the 1960s, with taking the province from the lowest rate of education — an average of only eight years of schooling in the 1950s — to the current level of performance.

‘Pre-university’ and ‘technical’ are the terms used by the Quebec Ministry of Education (Ministère de l’éducation et de l’enseignement supérieure, 2021) to describe the two college-level program categories. Some colleges, and some members of the college community, use other terms, particularly with regard to the technical programs. These programs may be referred to by some as ‘vocational,’ ‘career,’ or, simply, ‘three-year’ programs.

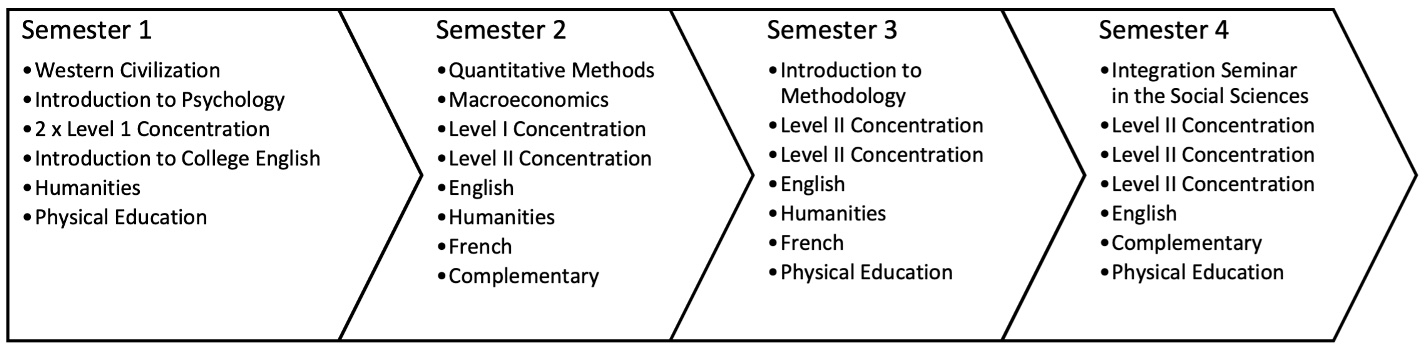

Note that unlike the corresponding university-level progression, course size is less likely to change over the course of the students’ progress through their program, as shown in the figure below (McDonnell, 2020). As such, even with foundational courses designed to introduce students to foundational concepts and a broad general knowledge of the subject, teachers have more opportunity to engage in the facilitator model of teaching and learning.

FIGURE 2. Progression and relative class size in Cégep program courses.

Depending on the program and college, minimum requirements vary; however, a review of local Cégeps confirm that most programs require a master’s or equivalent.

Article 5-2.00 of the FNEEQ (Fédération nationale des enseignantes et des enseignants du Québec) Collective Agreement (2016) outlines several paths to permanent status. Different colleges, and different departments, have different numbers of available full-time teaching positions, so that it may take as few as two years of full-time work, or as many as five, to become permanent.

References

Avidov-Ungar, O., & Forkosh-Baruch, A. (2018). Professional identity of teacher educators in the digital era in light of demands of pedagogical innovation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 73, 183-191. https://doi-org.lib-ezproxy.concordia.ca/10.1016/j.tate.2018.03.017

Badley, K., & Hollabaugh, J. (2012). Metaphors for teaching and learning. Faculty Publications—School of Education,52-67.

Borg, M. (2004). The apprenticeship of observation. ELT Journal, 58(3), 274-276. https://www.doi.org/10.1093/elt/58.3.274

Burgess, D. A. (1971). The English-Language CEGEP in Quebec. McGill Journal of Education, 6(001), 90-101. https://mje.mcgill.ca/article/view/6821

Champlain College. (2020, September 21). General Social Science. https://www.champlainonline.com/champlainweb/future-students/general-option-in-social-science/

Danielewicz, J. (2001). Teaching selves: Identity, pedagogy, and teacher education. University of New York Press.

Dawson College. (2021). Comprehensive Examination: Registrar. https://www.dawsoncollege.qc.ca/registrar/comprehensive-examination/

Dillard, A. (2013). The Writing Life. Harper Perennial.

Doucet, S. (2016). What is "A Good Teacher". Pédagogie Collégiale,29(5), 4-5.

Durocher, R. (2015, March 4). Quiet Revolution. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/quiet-revolution/

Enyedy, N., Goldberg, J., & Welsh, K. M. (2005). Complex dilemmas of identity and practice. Science Education Sci. Ed.,90(1), 68-93.

Fearon, J. (1999). What is identity (as we now use the word)? https://web.stanford.edu/group/fearon-research/cgi-bin/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/What-is-Identity-as-we-now-use-the-word-.pdf

Flores, M. A., & Day, C. (2006). Contexts which shape and reshape new teachers’ identities: A multi-perspective study. Teaching and Teacher Education,22(2), 219-232.

FNEEQ (Fédération nationale des enseignantes et des enseignants du Québec). (2016). 2015-2020 Collective Agreement. https://fneeq.qc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015-2020-Collective-agreement-FNEEQ-1.pdf

Fortier, I. (2007). One teacher's journey. Pédagogie Collégiale, 20(2), 1-2.

Gettysburg College. (2021). One third of your life is spent at work. https://www.gettysburg.edu/news/stories?id=79db7b34-630c-4f49-ad32-4ab9ea48e72b

Gini, A. (1998). Work, identity and self: How we are formed by the work we do. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(7), 707-714.

Izadinia, M. (2013). A review of research on student teachers’ professional identity. British Educational Research Journal,39(4), 694-713.

Lortie, D. C. (2005). Unfinished work: Reflections on Schoolteacher. In A. Lieberman (Ed.), The roots of educational change (pp. 133-150). Springer.

Magnuson, R. (1986). A brief history of Quebec education: from New France to Parti Québécois. Harvest House.

McDonnell, M. (2020). Raisins in the dough: Conversations on teacher identity and assessment practices (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, McGill University).

Ministère de l’éducation et de l'enseignement supérieure. (2021). College Education. https://www.quebec.ca/en/education/study-quebec/education-system

Perron, J. (2011). Le cégep: Plus que jamais synonyme d’enseignement supérieur! Les cégeps: 40 ans… et après ? Association des cadres des collèges du Québec, 5-12.

Pigeon, M. (n.d.). Education in Québec, before and after the Parent reform. http://collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/scripts/explore.php?Lang=1&tableid=11&tablename=theme&elementid=107__true&contentlong.

Thornton, A. (2011). Being an artist teacher: A liberating identity? International Journal of Art & Design Education,30(1), 31-36.

Trautwein, C. (2018). Academics' identity development as teachers. Teaching in Higher Education, 23(8), 995-1010.

Weimer, M. (2016, October 05). Why we teach: Exploring the teacher-as-midwife metaphor. http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-professor-blog/why-we-teach/?utm_campaign=Faculty Focus